You may not have heard of the word “arthropod” but you are certainly familiar with at least some members of this group: the insects. While insects make arthropods the most diverse phylum, arthropods also contains many other groups. Arthropods can be tiny (fleas) or fairly large (lobsters). They live in a variety of habitats: from the polar waters (krill) to the top of the trees (beetles) through arid deserts (scorpions).

On top of this diversity, arthropods are also economically important. For instance, mosquitoes carry the parasite which causes malaria, bees pollinate many of the fruits we eat, and the fruit fly is a model organism for genetic and medical research. Understanding how different groups of arthropods are related helps understand their evolution.

Scientists have been trying for a long time to understand how the different groups of arthropods are related to each other using morphological characters. This is not an easy task because arthropods are an ancient group. They appeared some 550 million years ago and all the extant groups were formed at least 200 million years ago. This is plenty of time to accumulate morphological differences which may mask the true relationships among extant groups.

This week, the journal Nature published a study that used an unprecedented amount of information found in DNA to understand how the major groups of arthropods are related. The results elucidate some long-debated issues about the relationships among various groups of arthropods. I highlight here two main findings.

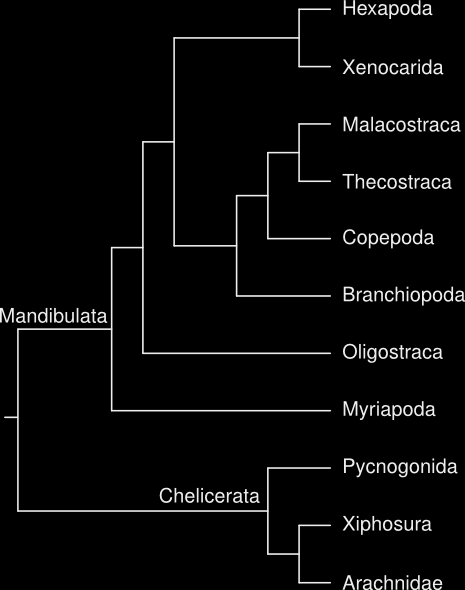

First, the authors confirm the results of previous DNA-based studies showing that the myriapods (the group which includes the centipedes and the millipedes) are not directly related to insects, and thus, that these two groups invaded land independently. It has been proposed that myriapods and insects were closely related because they both used special organs to breathe air. Furthermore, the myriapods are not directly related to the Chelicerata (spiders, scorpions, horseshoe crabs, mites, ticks) but belong to the Mandibulata (all the other arthropods).

Second, the closest relatives to the insects are a group of rare arthropods that the authors grouped under the new name of Xenocarida (“strange shrimps”). This new group unites two classes of arthropods that have only been recently described. In particular, the Remipedia were described in the 1980’s and are only known from a few places (the Bahamas, the Canary Islands, Mexico and Cuba) where they live in caves. This illustrates the issue of what is called “taxon sampling” when scientists try to infer the relationships among organisms. If the authors didn’t include these groups, the conclusions of their study would have been different, and some other arthropod group would have been mistaken for being the closest relatives of insects. Furthermore, it also illustrates the importance of habitat conservation and field work to preserve and discover species that can help unraveling the tree of life.

Link to the study:

- Regier et al, 2010. Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences. Nature.

More blog articles about the study:

- The most ambitious arthropod phylogeny yet — by Alex Wild at Myrmecos blog

- Blind Cousins to the Arthropod superstars — by Carl Zimmer at The Loom