If I say jellyfish, you probably picture a Frisbee-like animal with long tentacles that swims gracefully in an open ocean.

However, there is a group of jellyfishes (the Stauromedusae) that do things a little differently. First, they don’t swim but live attached to the bottom with a stalk, hence their common name: the stalked jellyfishes.

Second, they are thought to have a “simple” life cycle. Most jellyfishes

go through several stages before they reach adulthood. The typical

jellyfish starts life as a small polyp (something that looks like a sea anemone) attached to the ocean floor. This polyp buds small medusae (jellyfishes) that grow until they reach sexual maturity. At this point, they release gametes into the ocean. After fertilization, the egg forms a planula larva which will settle on the bottom to give rise to a new polyp.

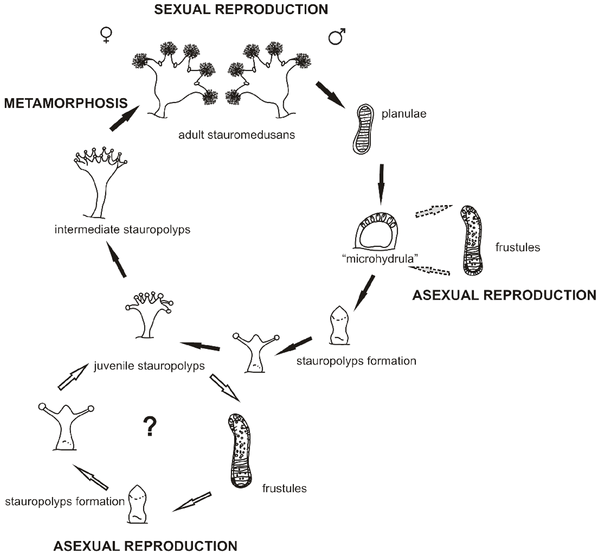

In stalked jellyfishes, things were assumed to be a little different, but simple: the planula attaches to the bottom and metamorphoses into a polyp (so far everything is normal). The top of the polyp metamorphoses into something that looks like a jellyfish while the bottom part stays the same and still looks like a polyp; hence a stalked jellyfish. The only problem with this story is that it is based on only a few observations based on few species, and it’s hard to know if all the Stauromedusae do the same thing.

There is another problem: how can you tell if the two stages of the life cycle that look very different belong to the same species? In the best case, you can observe the full life cycle in the field or in the lab, but it is not always possible to do so. In other cases, you can only observe part of the life cycle.

In 1996, Gerhard Jarms & Henry Tieman published a paper where they described a new species of hydrozoan polyps that live on clam shells of the Antarctic that they named Microhydrula limpsicola. They kept the animals in the lab for 4 years, and only observed asexual reproduction by frustules (larvae produced asexually).

In a recent paper, Lucilia Miranda and her colleagues demonstrated that Microhydrula limpsicola is just a stage in the life history of the stalked jellyfish Haliclystus antarcticus. They were able to connect these two life stages by discovering that the DNA of the polyps (what was thought to be M. limpsicola) and the stalked jellyfish (H. antarcticus) were identical.

The life cycle of the stalked jellyfishes is thus much more complicated than we thought.

Furthermore, Microhydrula limpsicola was not the only one of its kind. There are two other species that were thought to belong to this family (the Microhydrulidae). It will now be interesting to determine if they are also stages of other species of stalked jellyfishes.

Links

- Miranda LS, Collins AG, Marques AC (2010) Molecules Clarify a Cnidarian Life Cycle – The “Hydrozoan” Microhydrula limopsicola Is an Early Life Stage of the Staurozoan Haliclystus antarcticus. PLoS ONE 5(4): e10182. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010182

- Jarms G & Tiemann H (1996) On a new hydropolyp without tentacles, Microhydrula limopsicola n. sp., epibiotic on bivalve shells from the Antarctic. Sci. Mar. 60(1): 109-115 http://www.icm.csic.es/scimar/index.php/secId/6/IdArt/2742/

Credits

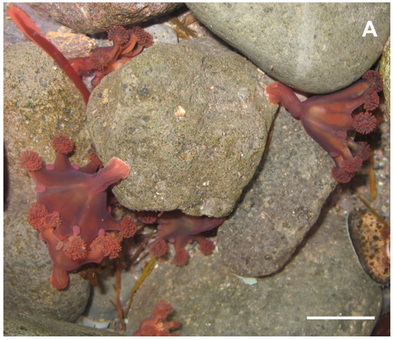

- Photo of jellyfish (top) François Michonneau. Lizard Island, February 2009. CC 3.0

- Photo of H. antarcticus and drawing of life cycle by Miranda et al 2010. CC 3.0

- Photo of the close up of a stauromedusa by Minette Layne CC 2.0