In the previous post, I introduced you to the species complex Holothuria edulis with the three players: the pink sausage, the gray one and the éclair. If one looks only at the ossicles, the character of choice to tell sea cucumber species apart, it seems like there is only one species. However, if one looks at the color of the animals and their ecology, it seems that the three players should be considered different species. Ideally, to distinguish species, it is good to have at least two independent characters that tell you the same story. Another important criterion to decide whether two individuals belong to the same species lies in whether they can produce fertile offspring. An efficient way to tell whether individuals can interbreed is to look at their DNA.

How can a succession of A, T, C and G (the base pairs) help to distinguish between species? Just like you, each cell in the body of a sea cucumber contains DNA that it inherited from its parents when the sperm and the egg fused. To create a fully functional organism based on this single initial cell, the DNA has to be duplicated many times. Because each cell contains its own copy of DNA, the DNA is fully duplicated before each cell division. There are many mechanisms to ensure that the duplicated DNA is a perfect copy. However, on rare occasions, mistakes are made. DNA molecules are large and some parts are more important than others. In parts that are not very important, these mutations can accumulate without many consequences. In important parts, the slightest alteration can have important results. Because of these differences, not all parts of the DNA molecules evolve at the same speed. Some evolve so fast that they are unique to each individual and can be used in forensics to convict or acquit a suspect. Some change so little that they are almost identical across the entire tree of life.

Where mutations happen very rarely, if you find two individuals that share the same one in their DNA, they are more closely related than individuals that don’t have this mistake. In other words, they share the same mistake because at some point in the past, their ancestors had the same parents. In animals cells, there is DNA in two compartments: the nucleus and the mitochondria. In the nucleus, each gene has two copies (one comes from mom, the other from dad) and the genes are arranged in long linear molecules: the chromosomes. The genes in the nucleus are responsible for most of the functions and appearance of the organism. Mitochondria are responsible for converting energy from sugars to make it available to the cells. In each mitochondrion, DNA is stored in a small single circular molecule and only contains genes that are useful to the mitochondrion. Unlike DNA in the nucleus, genes in the mitochondria are found in single copies: mitochondrial DNA from the parents don’t mix, and only the mother contributes. These characteristics make the evolution of mitochondrial DNA easier to track and understand than nuclear DNA.

Within the mitochondrial DNA, a gene has been widely used to help telling species apart. In most organisms, this gene accumulates mutations just at the right speed so that each species has a unique sequence. Because of this feature, the sequence of this gene can be considered as a “barcode”. Just like each product at the supermarket has a unique sequence of numbers represented as a barcode, the sequence of this gene is unique to each species. However, contrary to the barcode that is found on all the packs of your favorite cookies, the barcode found in the mitochondrial DNA of a species is not perfectly identical from one individual to the next. Instead, out of the about 700 letters that make up the barcode, it is common to find a dozen of differences between the two sequences, but it’s rare to find sequences that have more than 35 differences between two individuals of the same species.

Coming back to our species complex, what does the barcoding gene sequences have to say? The two most divergent barcode sequences that we have for the Holothuria edulis complex have about 20 differences, and they both belong to the pink sausage group. What is more surprising, is that the gray ones have exactly the same barcode sequence as some of the pink ones. The éclairs have their own unique sequence. However, they only have about 10 differences with some of the sequences from the pink ones.

If the barcode sequence was a perfect way to tell species apart, it would mean that the three color forms within this species complex are actually all the same species. However, it is not perfect. The three forms could actually be three good biological species that don’t interbreed, and yet, their barcode sequence could say otherwise.

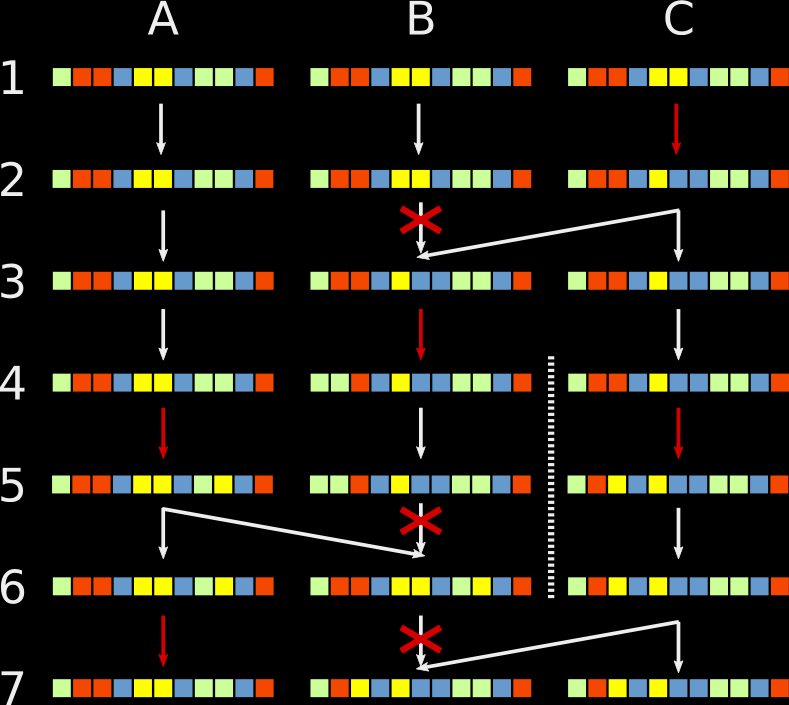

The first explanation to this pattern is these three form became different species very recently. Even when a species doesn’t interbreed with another, it takes many generations for the barcode sequence to be completely unique and characteristic of this species. At first, when a pool of individuals start to diverge from the rest of the population, they will carry with them only a small sample of the barcode sequences that were characteristic of the ancestral population. Generation after generation, some of these sequences will go extinct (because the individuals carrying them didn’t leave any descendants), and others will slowly accumulate mutations. Because these individuals don’t interbreed with the rest of the population, these mutations will become characteristic of this new divergent species.

An alternative explanation could be that these three forms are actually different species but recently they swapped their mitochondrial DNA. In species that recently split, it can happen that the mechanisms preventing different species to interbreed fail. They can hybridize and in the process mix up their DNA, and in particular mitochondrial DNA. If it were the case, the signal shown by the barcode sequence could be misleading. The species may have stopped interbreeding a long time ago, but if they swapped their mitochondrial genes recently, the information from the barcode gene would be make us think that they belong to the same species.

The alternative to these hypotheses could be that the barcode gene is correct: the three forms are actually the same species and they just look different because they live in different habitats for instance.

In the end, we are in a situation where color patterns and ecology say one thing (the three forms are different species) while ossicles and genetics suggest another (the three forms are the same species). Which is right? To understand what is happening in this particular case, in the next months, I am going to look at what nuclear genes have to say about it. Remember, mitochondrial genes only show a small part of the story as they are transferred only through the mothers. Nuclear genes, in particular those accumulating mutations faster than the barcode gene, could help explain what we observed in the mitochondrial DNA, and in turn, help us understand whether the pink sausage, the éclair and the gray one are the same species.