There is perhaps some subtle irony in that studying animals that can weigh several kilograms and can be longer than a loaf of French bread require a microscope to study. Yet this is the case with sea cucumbers as their ‘skeleton’ is made up of bony plates called ossicles and these ossicles are the main character used to distinguish closely related species.

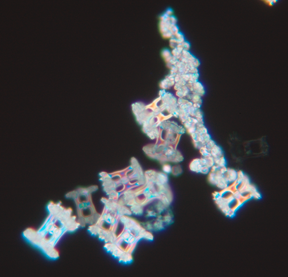

Just to add another layer of difficulty to the proposition of looking at these wee bones, most of them are also clear. On the right is an image of ossicles from a Stichopus species taken with a standard compound microscope using polarizing filters. Light is passed up through a slide with ossicles on it and it is then possible to observe the image through the eyepiece or take a photograph.

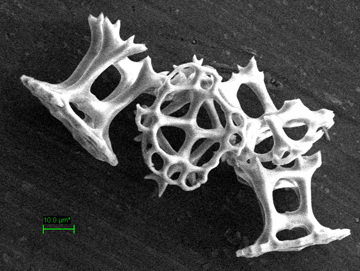

Now trying to visualize, let alone illustrate, something that is tiny, clear and in many cases three-dimensional is challenging. Think of trying to take a photo of a glass with someone standing behind it shining a flashlight at you! Happily, here at the University of Florida several departments have scanning electron microscopes (SEMs). Now SEMs bounce electrons off the surface of objects and the imaging system provides an opaque view of the object- imagine the image you would get spray painting the glass from our previous example with white paint before taking a photo.

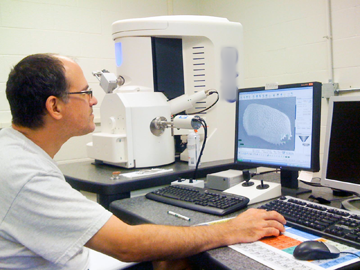

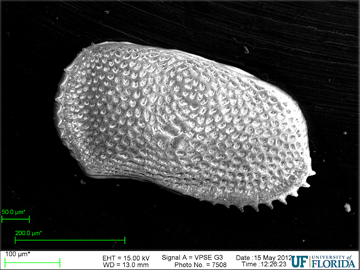

What does an SEM look like? Below is a picture of George Hecht, FLMNH’s resident ostracodologist, using the UF Geology Department SEM to image a valve of one of the tiny crustaceans he studies. Below that is an image of George’s ostracod and it is followed by an example of sea cucumber ossicles.

The Stichopus ossicle SEM above provides a much clearer representation of the three-dimensional nature of the ossicles compared to the light micrograph image that started this article. Look for more photos in coming weeks as we expect to do quite a bit of imaging of not only of ossicles, but other tiny organisms, or at least tiny pieces of larger organisms, over the course of this summer.