This post was written by guest blogger Noah J. D. DesRosiers, a research colleague who accompanied the FLMNH team on the KAUST Red Sea cruise. You can read more from him at www.naturenoah.com.

“Thousands of miles from home, hundreds of miles from our institution, and thirty miles from any solid land, I am falling slowly into darkness. Checking my life support system, I find my breathing gas cylinder is fully charged, its valves are open, my facemask is cleared, and the needle on my depth gauge is steadily rising as the twisted crags of a monstrous limestone wall climb ever higher over my head. I break the silence with periodic Vader-esque respiration. At nearly a hundred feet down I push a button to halt my descent, which leaves me hanging motionless in the depths. Feeling around my shoulder, my fingers recognize and unclip a bag of sampling equipment from my rig and I kick forwards towards the wall. I am crossing over a thousand feet of liquid blackness that falls further still beneath me, a murk laden with swirling creatures staring upwards that I’ll never know. The light I’ve carried with me beats back shadows to reveal a gnarled jungle of swaying and crawling non-terrestrial life on the wall’s surface. Bejeweled green, yellow, red, and silver eyes flash on and off from numerous tiny caves. While sweeping my light across the deep reef’s surface, the apparition of a nightmarish creature stops me suddenly, and my breath catches. With a steady gaze I reach for a jar, unscrew its lid, and cautiously move it towards the creature. Bright red claws sway from side to side as the jar draws nearer; mysterious green eyes appear locked on mine. Using the beam of light alone, I herd the photo-phobic creature backwards into my jar, using my last ounce of breathless concentration to carefully screw on the lid. With the cover in place, I exhale jubilantly, relieved to respire again. I bring the jar close to study my mysterious prize; flecked with yellow, blue, purple, and white, the almost clear body of this potential new species broods within its flimsy cage of plastic, issuing an occasional defiant CLICK! A flash of light from a camera draws me from my reverie; Dr. Paulay is nearby. Looking over, I see him in a similar struggle with the strange, his dive light silhouetting his head in a dim halo. Craning my head upwards to the distant surface, the distorted outline of the moon is surrounded by the eery contours of the midnight reefscape. I take a deep breath before returning to the search for undiscovered life, and think that surely not even astronauts feel like this.”

The above account, of a thrilling night dive I made with FLMNH’s Dr. Gustav Paulay on a deep offshore reef wall, comes from my log of a recent expedition to the Saudi Arabian Red Sea (in Arabic, Al-Bahr Al-Ahmar). The two week cruise, organized by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), was planned as the first of five such cruises to make a rigorous survey of the region’s marine biodiversity. Crossing nearly four degrees of latitude, our journey took us to points south in the Red Sea around the Farasan Islands (click to see our cruise map). 17 scientists (including professors, researchers, and students) from various institutions around the world participated, including various taxonomic specialists (Dr. Arthur Anker, shrimps; Dr. Sancia van der Mejj, gall crabs; Dr. Terry Gosliner, sea slugs; and Dr. Howard Choat, parrotfishes, to name just a few). And while coral reefs are always beautiful places to survey, the Red Sea’s elevated temperature, consistently calm weather, and exceptional water clarity made our expedition particularly breathtaking.

As soon as the sun was up each morning, we’d gather around the dining/lounging/data entry area of our floating home, the 85-foot liveaboard vessel Dream Master. Over eggs, toast, and Spam we discussed the previous day’s events, laughed at each other’s morning appearances, and planned the objective for the current day’s dives. You wouldn’t know from our appearance that we were actually a room full of professionals with years of schooling, madly pumping out written records of our sub-sea discoveries; salt, scales, and slime are the field researcher’s haute couture. Assuming we weren’t hastily steaming south (local operators prefer not to navigate at night) we’d be suiting up and ready for our first dive by 9:00 AM.

The scientists were loosely organized into two working groups – those collecting fishes, and those surveying and collecting invertebrate animals. Some researchers, like our cruise organizer Dr. Michael Berumen, managed to assist all teams at one point or another in their collecting needs. Your humble narrator attempted the same, only to realize when bogged down with spears, jars, vials, bags, clips, camera, forceps, bottles, brushes, and nets – that it had been too long since I’d last hunted a fish. Avoiding the ridicule of my quarry (I swear fish laugh at you when you miss) I decided to focus on the invertebrate collecting, which offered interesting new sampling techniques of its own.

As a prospective student, I had heard of Dr. Gustav Paulay’s legendary collecting ability. Now, I watched it unfold before me each evening when, after two or three dives, the sun deck of our vessel was turned into a seething menagerie of abducted marine life. Most of the other invertebrate biologists on board had worked with Dr. Paulay before, and they prepared themselves for specimen processing like dancers stretching before an arduous performance. Certainly the work required poise; night after night workstations arose for specimen identification, labeling, relaxation (for the specimens, that is – science is too fun to take breaks), photography, DNA subsampling, and ethanol fixation. And the star of the show each evening was Dr. Paulay; pirouetting past each plastic container, identifying every squirming specimen, and occasionally shouting with glee, “Ah, ha! Oh ho!” The professor’s strength is his lasting excitement, carrying us all forward, as if every night were opening night in the biodiversity ballet.

While the upper deck was awash with invertebrates each evening, the dive platform at the stern was being covered with scales. There, fish researchers measured, weighed, dissected, and at least once “subsampled” with lemon and soy sauce, their day’s catch. A central theme of their research focused on evolutionary phylogenies; DNA from collected rare, native, or wide-spread species will be used to determine relatedness between species or populations, and thus aid in constructing part of the timeline of evolution. With no railings around the dive platform, they could clean up with a quick dip in the sea – and enjoy the best view!<

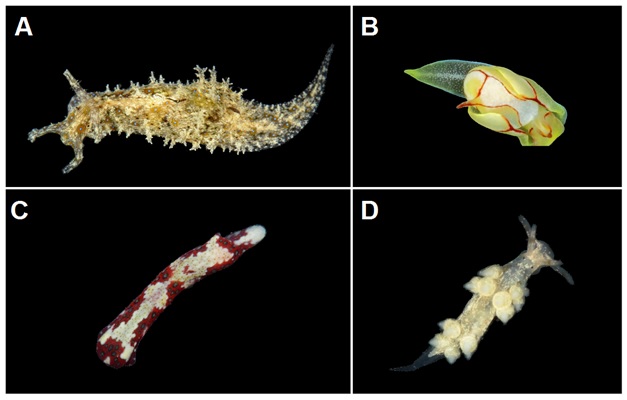

Your narrator, once also a mere fish biologist, now spent his time primarily chasing sea slugs. Dr. Terry Gosliner and I ended up collecting 88 different species! Since their colors are so charismatic, it is actually common for a species to be known from a locality (from divers’ photographs or generic collections) before it has been given a scientific name. Though we found plenty of known species, we also found others that have never been documented before! The area is rich for discovery; I found four species crawling over rocks on the jetty the night before Dream Master even left port, and one of those was a new species!

Of course, no reef research trip would be complete without studying the corals, the ecosystem’s architects! KAUST doctoral candidate Jessica Bouwmeester assisted Dr. Francesca Benzoni of the University of Milano-Bicocca to establish a specimen reference collection of Red Sea coral species. After just two weeks, they believe their collection represents 80% of the Red Sea coral diversity, and can now be used by all visiting scientists for further study! Dr. Sancia van der Mejj of the Netherlands’ Naturalis Biodiversity Center worked right alongside the pair, as her study organisms burrow into live coral (the gall crabs). Dr. Michel Claereboudt of the Sultan Qaboos University in Oman meandered through the group, occasionally helping with local species identification, while pursuing his own questions on the marine biodiversity of the Arabian Peninsula. The reef is an interwoven network of life; so too the efforts of those who toil to know its secrets.

Overall, it was a very productive trip for everyone. Much work remains to be done studying all those new samples! But those are stories for another time. For now, I will end this post with an MVP award. Without hesitation, the coveted title(s) go to Dr. Art Anker and his faithful sidekick Norby. The pair achieved museum-quality photography of most of the identified specimens – over 3,000 individuals – after each full day’s diving, on a rocking boat in windy seas without a tripod, often until 2 in the morning. Though nary a (serious) complaint was heard, poor Art spent more time talking to alpheid shrimps than people, and we do all so hope that his return to Singapore included “liquid re-integration therapy” lest he begin growing antennae of his own! ♠

(Many thanks to Tane Sinclair-Taylor, field technician at the KAUST Red Sea Research Center, whose exceptional photographs bring this story to life; our hard-working Filipino captain and crew, who navigated, cooked, cleaned, and kept us afloat; and Jean-Paul Hobbs, a fish researcher on this cruise whom, despite being a strikingly handsome young fellow from the University of Western Australia, I could not work into this narrative. Better luck next time, mate!)

This is wondrous!