Lepidoptera species generally have different wing patterns which help identify them. Nevertheless, look-alikes and plain colored species can be a challenge, especially with tiny moths. Long before DNA barcoding became a popular identification tool, Lepidopterists relied on what is still the inexpensive gold standard – genitalia dissection.

Butterflies and moths, like all insects, have an exoskeleton made of chitinized or hardened cuticle. Their genitalia, consisting of the phallus and terminal appendages (e.g., claspers) of males and the ovipositor and invaginated mating receptacles of females, are also made of chitinized cuticle. These hidden morphological features are uniquely shaped in each species and often include elaborate ridges, knobs, and spines which are darkened or thickened with sclerotin (sclerotized). In males, the claspers and other structures help lock the male and female abdomens together during mating. This special mechanical fit, referred to in scientific literature as the “lock and key” hypothesis, together with sensory cues such as pheromones and mating dances, help ensure males and females of the same species mate.

Various techniques are used to examine and study genitalia. In some cases, this may involve using a small paintbrush or feather to brush away scale tufts at the tip of the abdomen and expose the cuticle. In other cases, the entire abdomen is removed for an actual dissection. For the latter, the abdomen is treated in a “potash,” potassium hydroxide solution to dissolve away fats and soft tissue, leaving the cuticle and sclerotized parts behind.

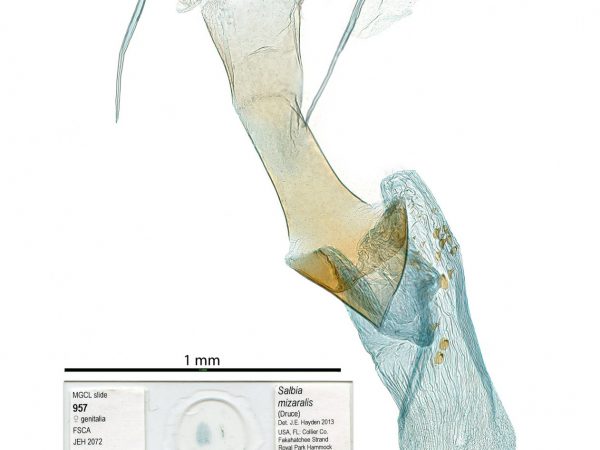

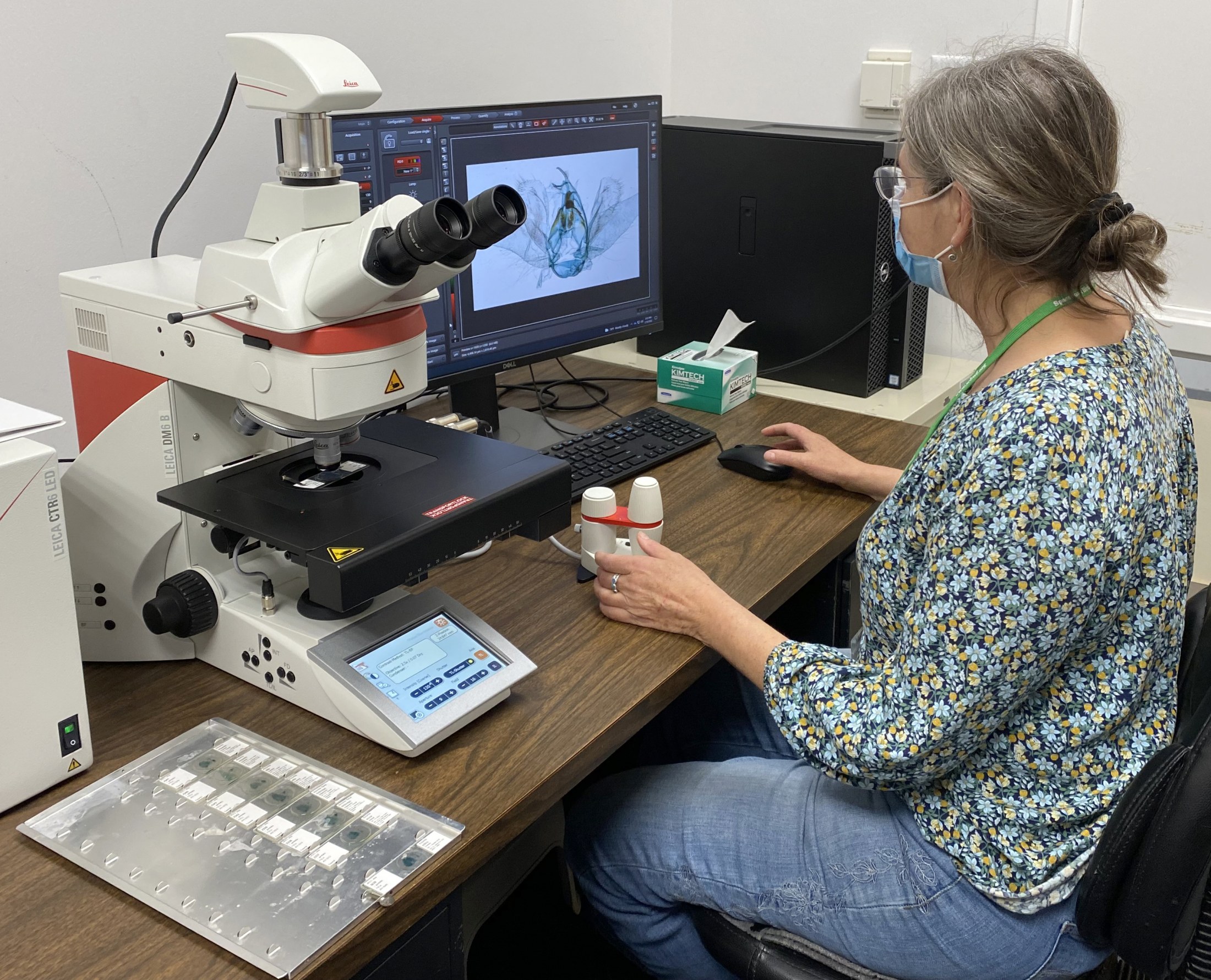

Once cleaned and stained with a dye to improve visibility, the genitalia and “pelt,” or skin of the abdomen, is permanently stored in vials containing glycerin or mounted on glass microscope slides.

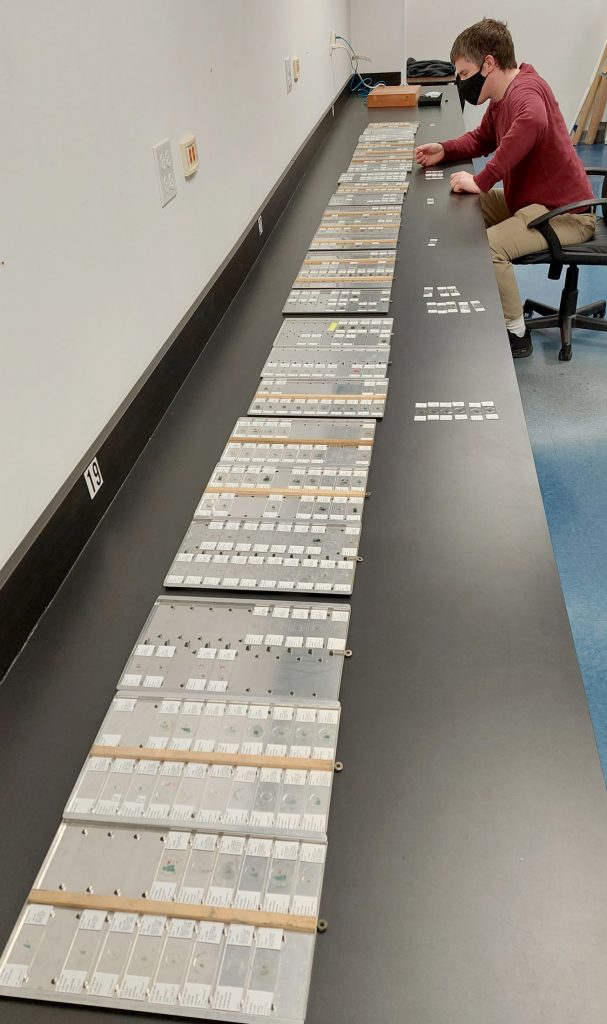

The McGuire Center has a large collection of more than 19,000 genitalia slides, each labeled and numbered to match the corresponding pinned adult from which the abdomen was removed. Dissections on slides and in vials have been contributed by generations of Museum staff and also by donors of major collections, such as T.S. Dickel, L.C. Dow, and E.C. Knudson, who dissected to identify their specimens and to discover new species. These slides are a tremendous resource which has been stashed away in boxes and various cabinets around the Center.

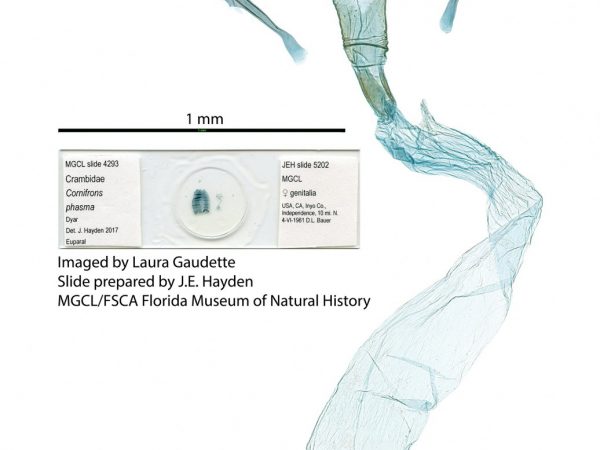

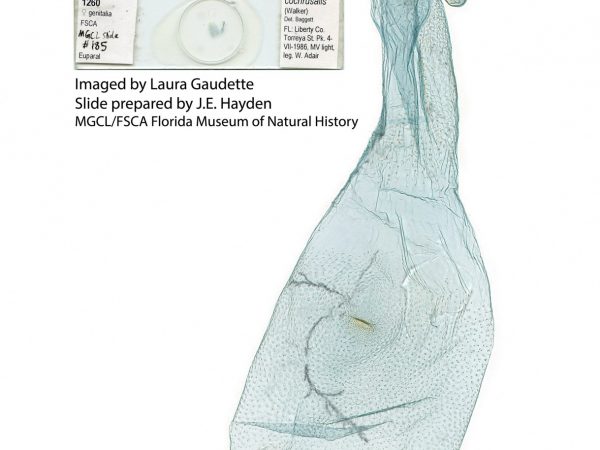

McGuire Center staff members Deborah Matthews and Jim Hayden, together with museum volunteer Laura Gaudette and technical support staff, are working on organizing and digitizing parts of this collection to make this resource accessible to all. With a focus on microlepidoptera of Florida and the southeast, as well as potential pests and invasive species, they are assembling composite images of selected slides. These images will be available through the iDigBio portal and the Moth Photographers Group website.

Although a delicate process, dissection is very low-cost tool which does not require much more than a steady hand, some basic chemicals and tools (probes, forceps etc.), and a stereo microscope.

As the need for local and regional biodiversity inventories increases, researchers and citizen scientists find that images of live moths by themselves are not always enough to identify some groups of microlepidoptera, even with help from taxonomic specialists. Many moth photographers are taking the next step and preparing dissections of difficult species. Digitization of existing slide preparations provides a ready resource for comparison.

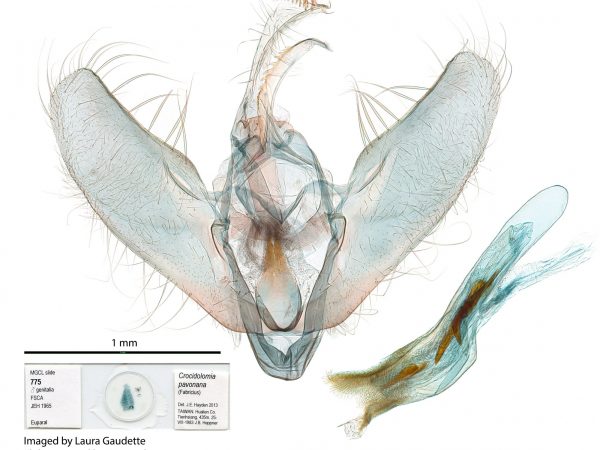

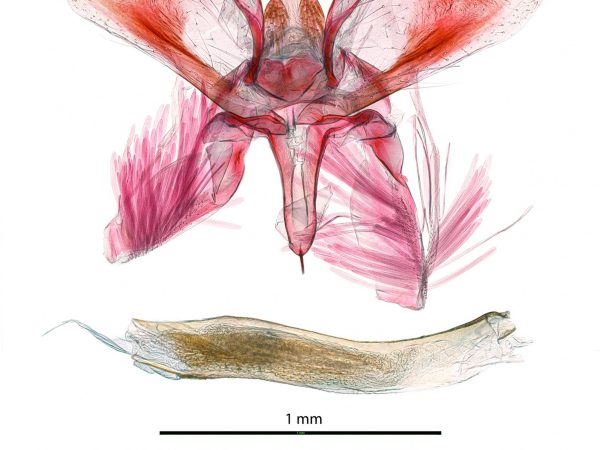

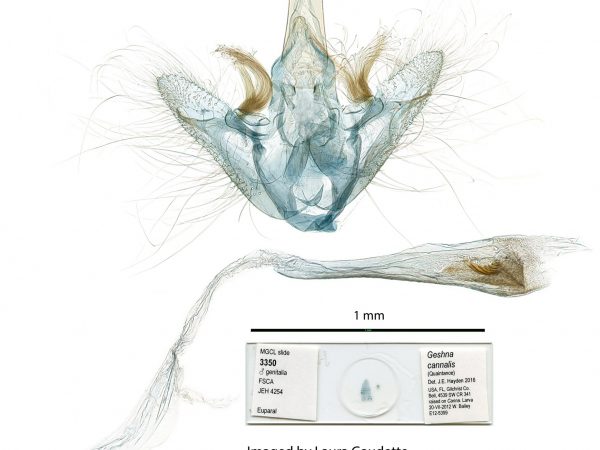

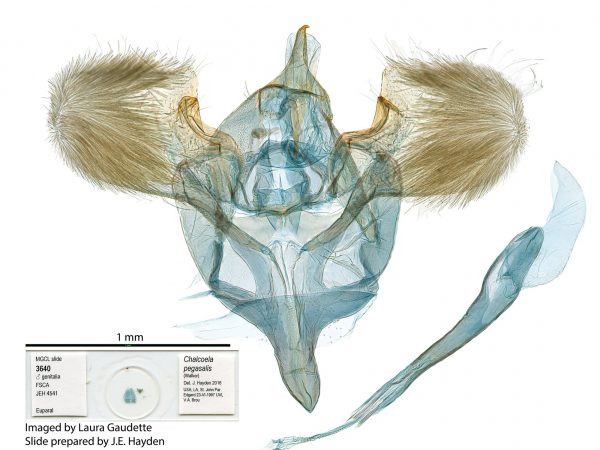

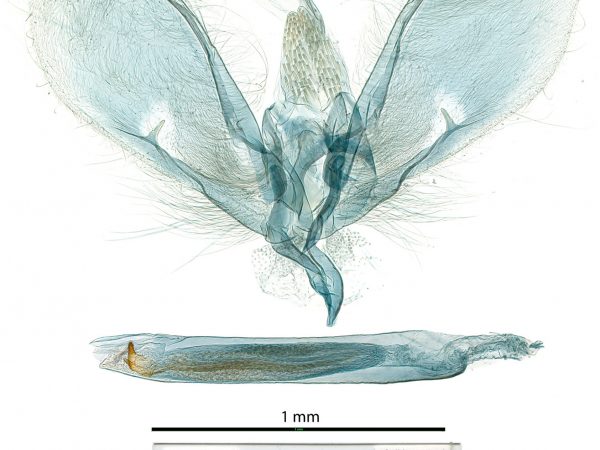

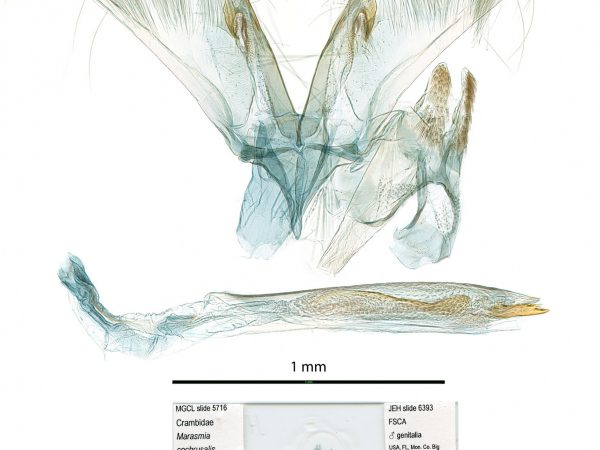

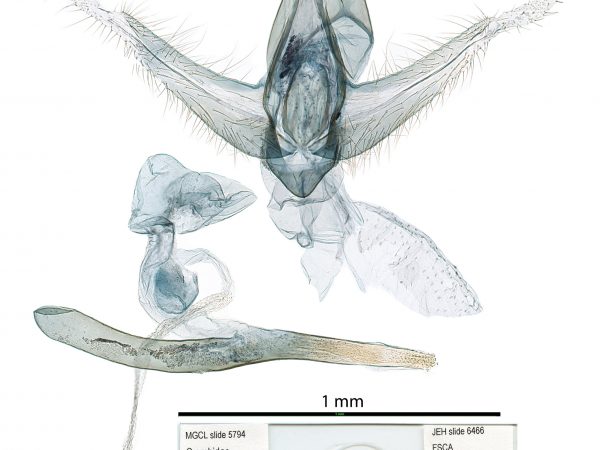

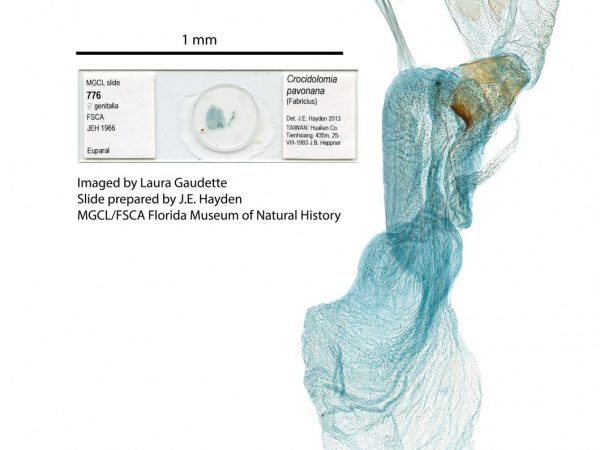

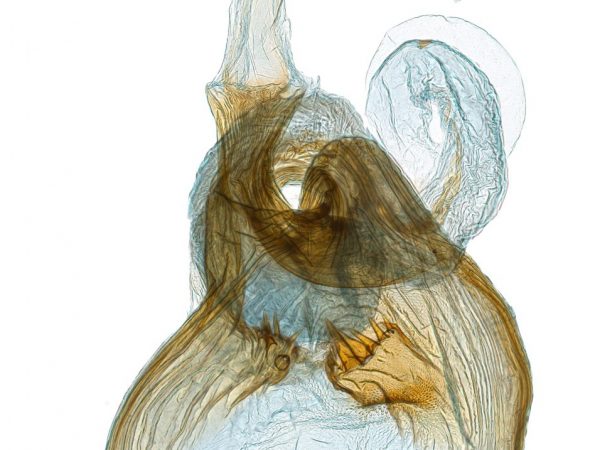

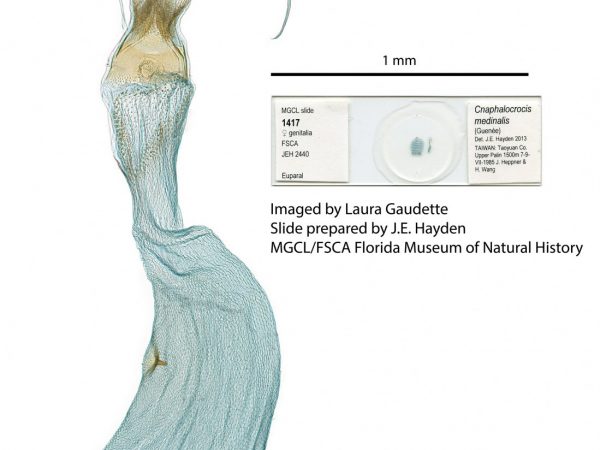

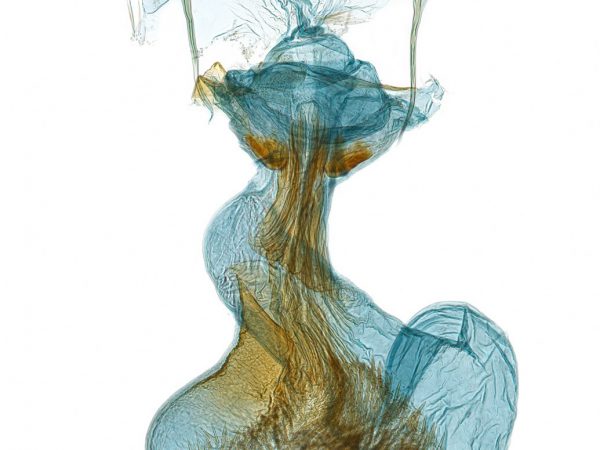

Some sample images of the moth family Crambidae are shown in the gallery below (click to enlarge).

Male genitalia of Crocidolomia pavonana.

Male genitalia of Crocidolomia pavonana. Male genitalia of Salbia melanobathrum (Crambidae)

Male genitalia of Salbia melanobathrum (Crambidae) Male genitalia of Geshna cannalis.

Male genitalia of Geshna cannalis. Male genitalia of Chalcoela pegasalis.

Male genitalia of Chalcoela pegasalis. Male genitalia of Salbia tytiusalis.

Male genitalia of Salbia tytiusalis. Male genitalia of Marasmia cochrusalis.

Male genitalia of Marasmia cochrusalis. Male genitalia of Cybalomia extorris.

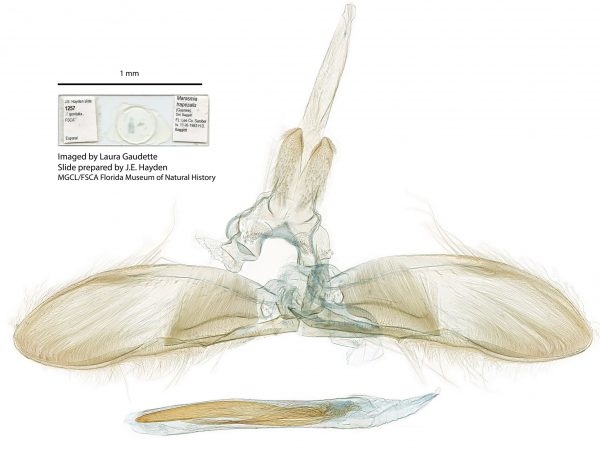

Male genitalia of Cybalomia extorris. Male genitalia of Marasmia trapezalis.

Male genitalia of Marasmia trapezalis. Male genitalia of Alatuncursia bergii.

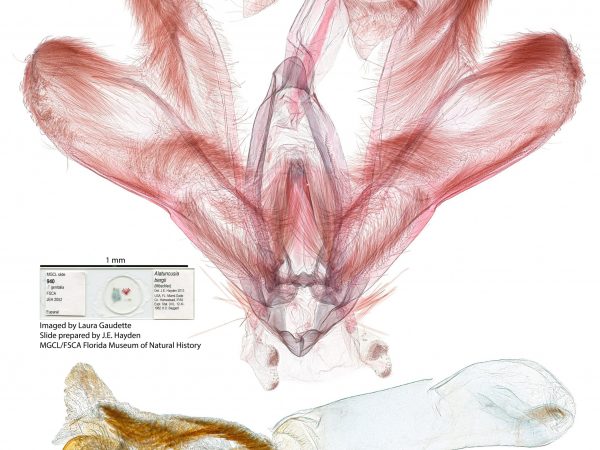

Male genitalia of Alatuncursia bergii. Male genitalia of Salbia haemorrhoidalis.

Male genitalia of Salbia haemorrhoidalis. Male genitalia of Aethiophysa delicata.

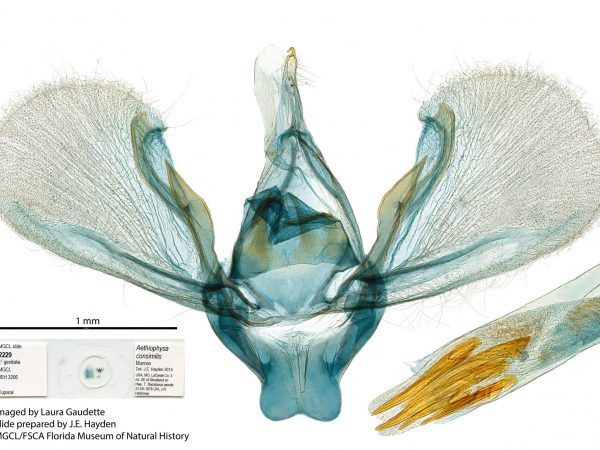

Male genitalia of Aethiophysa delicata. Male genitalia of Aethiophysa consimilis.

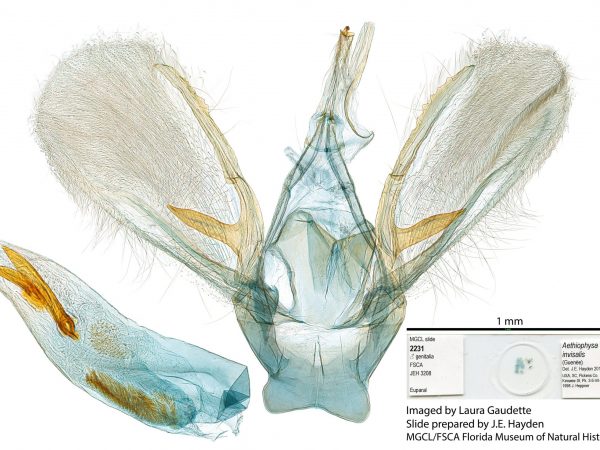

Male genitalia of Aethiophysa consimilis. Male genitalia of Aethiophysa invisalis.

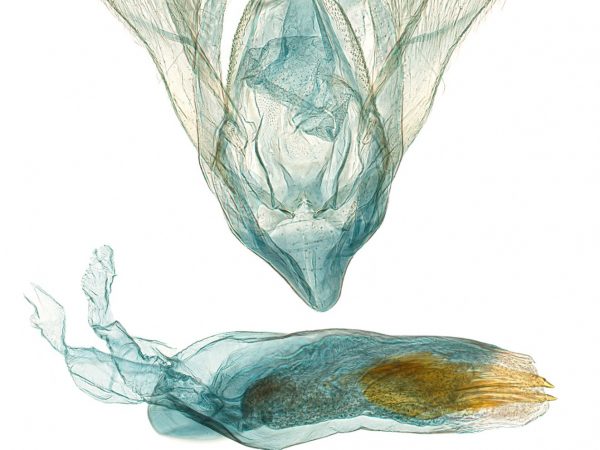

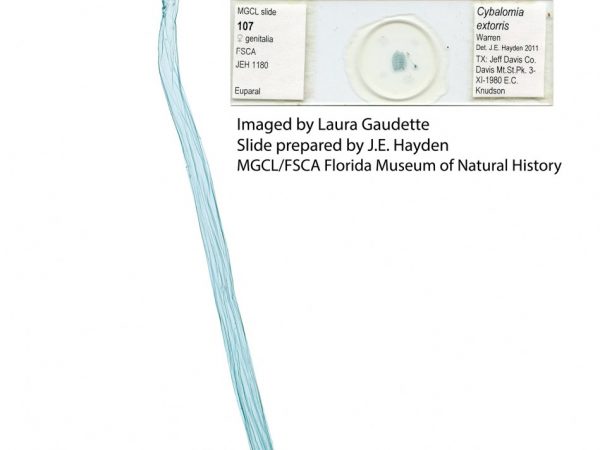

Male genitalia of Aethiophysa invisalis. Female genitalia of Cybalomia extorris (Family Crambidae).

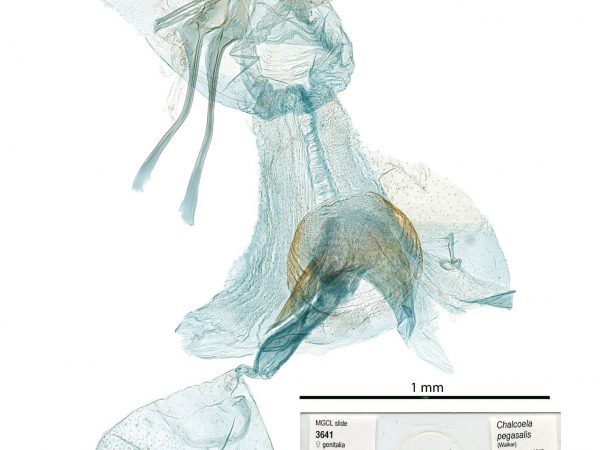

Female genitalia of Cybalomia extorris (Family Crambidae). Female genitalia of Chalcoela pegasalis.

Female genitalia of Chalcoela pegasalis. Female genitalia of Salbia melanobathrum.

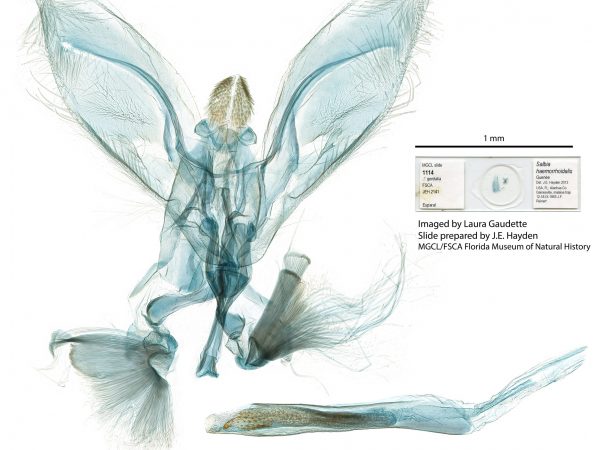

Female genitalia of Salbia melanobathrum. Female genitalia of Salbia tytiusalis.

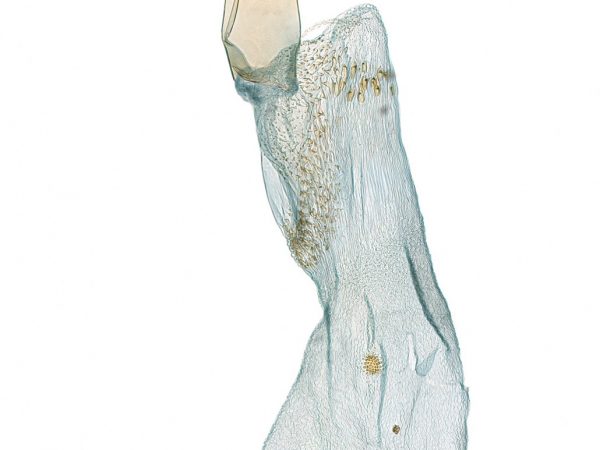

Female genitalia of Salbia tytiusalis. Female genitalia of Cornifrons phasma.

Female genitalia of Cornifrons phasma. Female genitalia of Marasmia cochrusalis.

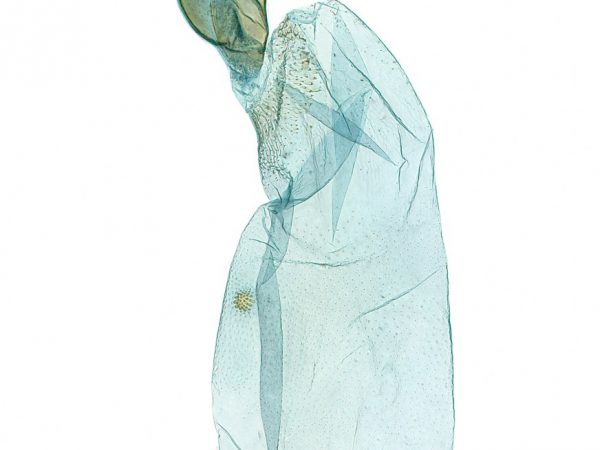

Female genitalia of Marasmia cochrusalis. Female genitalia of Crocidolomia pavonana.

Female genitalia of Crocidolomia pavonana. Female genitalia of Alatuncusia bergii.

Female genitalia of Alatuncusia bergii. Female genitalia of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis.

Female genitalia of Cnaphalocrocis medinalis. Female genitalia of Aethiophysa invisalis.

Female genitalia of Aethiophysa invisalis. Female genitalia of Salbia mizaralis.

Female genitalia of Salbia mizaralis.

For information on basic Lepidoptera genitalia dissection techniques check out the following videos by Cornell graduate Kyle Austin: