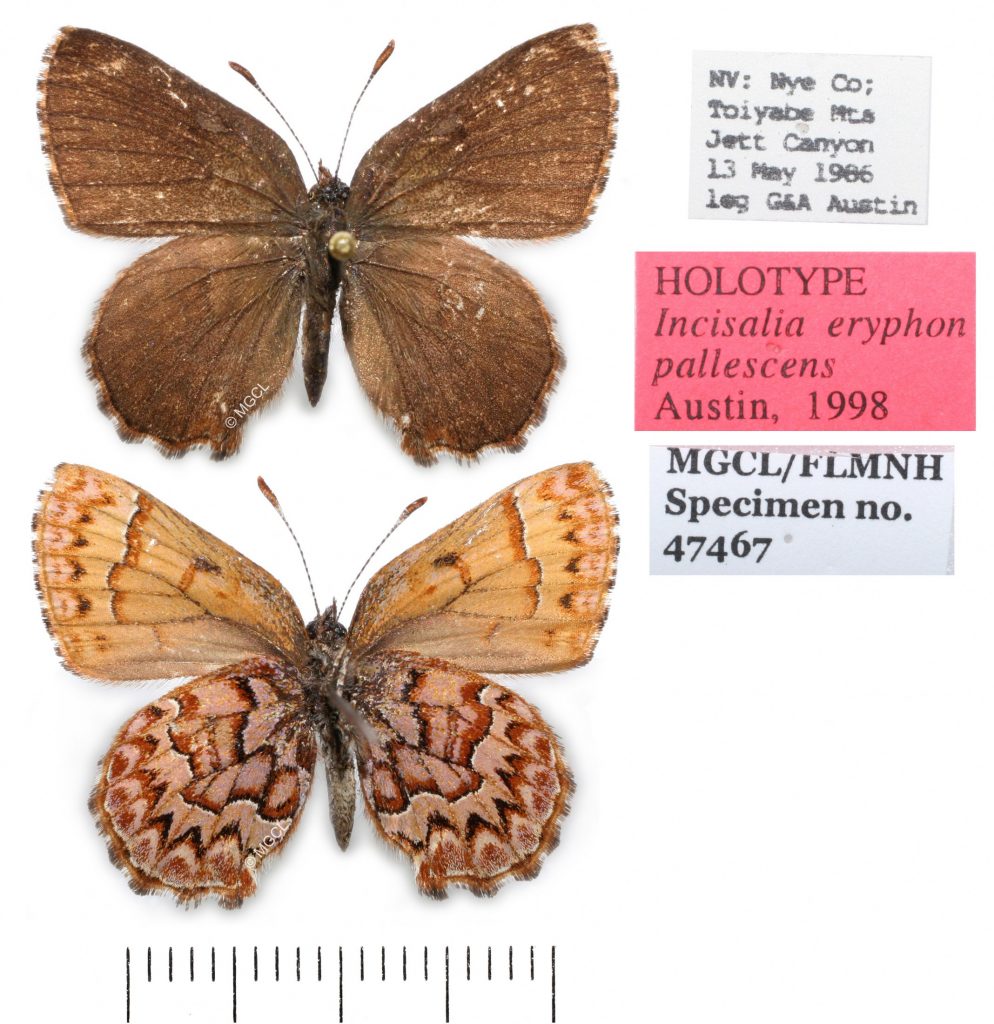

The McGuire Center Lepidoptera collection includes a modest number of what are known as “type specimens.” When researchers name and describe a new species or subspecies of butterfly or moth, they have a set of specimens before them that are closely examined in order write a verbal description and illustrate the distinguishing morphological and anatomical features of the new taxon. Sometimes there is only one specimen to work with; usually there are several and the researcher chooses a single representative specimen to be the holotype. When the description and name are published, the holotype then becomes the name-bearing specimen for the new species or subspecies and the rest of the specimens in the series examined become paratypes. The holotype is thus extremely important and scientifically valuable for comparisons. Other specimens that match the holotype in visible features or DNA can then be determined to belong to the same species as the holotype. Animal names and type nomenclature follow rules set by the International Code of Zoological Nomencature, while algae, fungi and plants follow a different code.

There are many kinds of types in both realms. For animals, up until the the last century a single type was not always chosen, and instead a set of syntypes (sometimes improperly referred to as cotypes) were used to describe a species. In these cases, later researchers may choose to formally (in a scientific publication) designate one of these syntypes to become the single name-bearing specimen, called a lectotype. In the event that the holotype is lost or destroyed and there are no existing paratypes, a new name-bearing specimen may be selected to be the neotype. Name-bearing types (holotypes, syntypes, lectotypes, and neotypes) are considered primary types and these specimens receive special treatment in our collections.

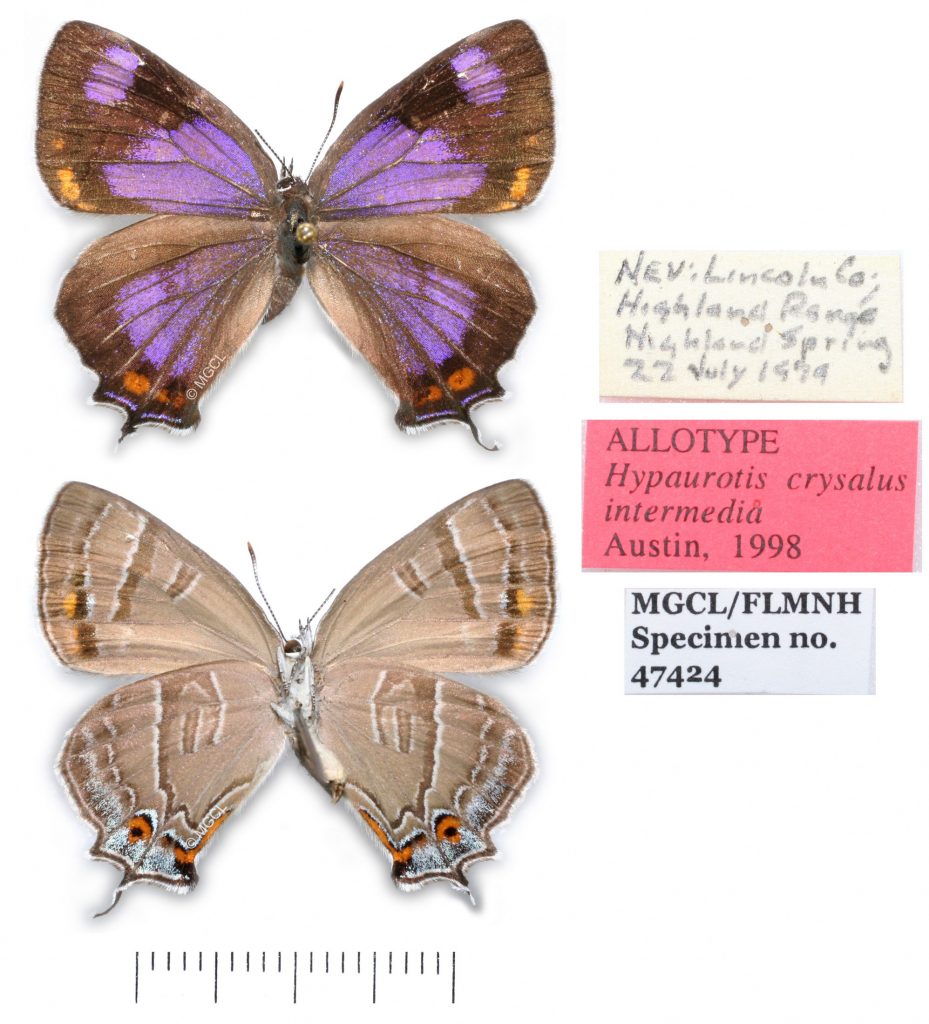

The McGuire Center currently houses more than 1,362 primary types of Lepidoptera, including those from our partner institution, the Florida State Collection of Arthropods. These types are kept in tight-fitting drawers in a designated area of closed cabinets separate from the main collection ranges. Each specimen may be given a separate unit tray for extra protection. Color-coded labels with the species or subspecies name are typically placed on type specimens by the describer. Red is used for holotypes, while blue is usually used for paratypes. When describing new species or subspecies, some researchers also elect to designate allotypes. An allotype is a specimen selected from the series of specimens examined that is the opposite sex as the holotype. While not considered primary types, the McGuire Center also separates and stores allotypes within our type cabinets. Many examples of species and subspecies with allotypes were described by our late Collection Manager, George T. Austin. Allotypes are particularly useful when species or subspecies display sexual dimorphism, in other words, the wing patterns of males and females are noticeably different.

In addition to the steady accumulation of holotypes from publications by the Center’s staff and associates, our type collection is especially rich in type material from historic collectors like Eugène Le Moult and William James Kaye. Many of these types were part of the Allyn Museum of Entomology collections which were moved to Gainesville in 2004.

The advancement of molecular techniques has sparked keen interest in the utility of not only mitochondrial DNA ‘barcoding’, but also sequencing across the entire genome from type material. McGuire Center Research Associate Nick Grishin makes frequent visits to the Center in order to obtain tissue samples for DNA extraction from our collections. His lab at the University of Texas Southeastern Medical Center and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, through techniques perfected by researcher Qian Cong, has been able to obtain genomic sequences from type specimens collected more than 150 years ago!

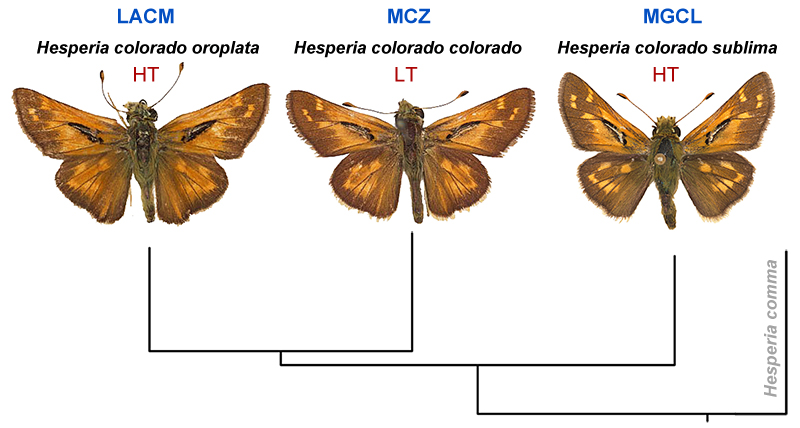

In a particularly fascinating study published in 2021, Grishin’s lab teamed up with McGuire Center Senior Collection Manager Andy Warren, and McGuire Center Research Associate John Calhoun, to unravel mysteries surrounding type localities (the place where a type specimen was collected) and subspecies distributions of the Western Branded Skipper, Hesperia colorado. The location where the lectotype of H. colorado was collected was not indicated on the specimen label, just the date “7-13”. Because several H. colorado subspecies look very similar, figuring out where the lectotype was collected was critical to determining how to apply different names to geographic populations. By comparing genomes of recent populations to that of the lectotype of H. colorado, and researching the 1871 expedition travels of the collector, Theodore Mead, the team was able to pinpoint the collection locality to a 15km diameter area in Lake County, Colorado. Having this type locality established for the first-named (or nominotypical) subspecies (H. colorado colorado) allowed them to further analyze two other somewhat isolated river basin populations, as well as a nearby but higher elevation alpine population, and confirm the genetic parameters of these previously described subspecies, H. colorado idaho, H. colorado ochracea, and H. colorado sublima. The team similarly established the separate species-level status of North American H. colorado from its Eurasian counterpart, Hesperia comma, correcting prior erroneous classifications of H. colorado as a subspecies of H. comma. The scope and impact of the Hesperia study is one of many in-depth projects demonstrating the scientific value of type specimens.