“We’re the best of our kind [university and state museum] in this hemisphere. I truly believe that.”

— J.C. Dickinson

This year (2006) marks the centennial of the Florida Museum on the University of Florida campus. Such a big number inspires reflection, and this combined with the 90th birthday of former director Joshua Clifton (J.C.) Dickinson prompted us to peer into our past. Over the summer, I had the pleasure of unearthing some of the archives and conducting a series of oral history interviews with J.C. This brief story recounts some of that interaction, the full transcripts of which will become available through the university’s Oral History Program archives. During Dickinson’s 20-year tenure as director, the Museum underwent unprecedented growth in research and education programs, built its first signature building (Dickinson Hall) and became the national powerhouse that it is today.

Although not officially chartered by state law until 1917, the Museum had a much earlier identity. Our records indicate that collections were first assembled as a teaching resource in 1891 by Frank Pickel, a natural science professor at the Florida Agricultural College in Lake City. The collections grew by donations from other professors until the school closed in 1905. In 1906, the collections were transferred to the new University of Florida campus, and thus began the genesis of our museum. Displayed first in dormitory Thomas Hall, the collection moved to the basement of Science Hall (later named Flint Hall) in 1910. Thompson Van Hyning was named Museum director in 1914.

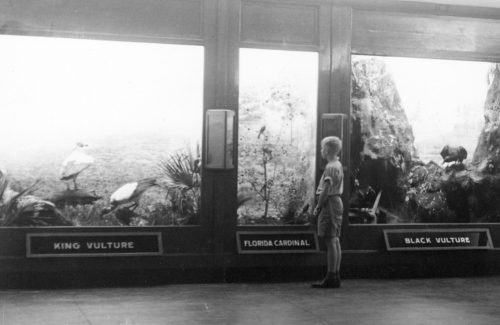

Van Hyning oversaw the early years virtually unassisted, with a secretary and later a preparator. Connections to the Zoology department led to collections growth and use, and the Museum also was open to the general public. Van Hyning worked toward an exciting plan for a prominent new museum building to be sited at the northeast corner of campus – one of Gainesville’s busiest intersections, University Avenue and SW 13th Street. A change in administration brought this dream to a close, and a frustrated Van Hyning instead moved the Museum downtown to the Seagle Building. The new museum opened to the public in 1939, and busloads of school children enjoyed the exhibits for years. Displays that now look old-fashioned were comparable to those at other university museums such as Harvard and Yale. Cases displayed objects by subject matter, and dioramas featured mounted animal specimens in their natural habitats.

Upon Van Hyning’s war-time retirement in 1946, UF President Tigert asked preparator Nile Schaffer to serve as acting director until a university task force named biologist Arnold Grobman director in 1951. Grobman began to professionalize the Museum, and initiated three departments – Natural Sciences, Social Sciences and Exhibits – and hired three employees to head the departments. The Natural Science hire was biologist J.C. Dickinson. State Archaeologist Ripley Bullen headed up Social Sciences and Gilbert Wright from the Illinois State Museum led Exhibits.

Dickinson was no stranger to the Museum. In 1933 he moved from his boyhood Tampa home to attend UF as an undergraduate. The Zoology department shared Science Hall with the Museum, and Dickinson reports a strong rivalry between the groups. His first contribution to the Museum was inadvertent – a donation to Zoology of 33 lots of native Florida fish, later absorbed by the Museum. Dickinson remained at UF, interludes aside (at the University of Virginia for some undergraduate studies, and during World War II as an instructor for the U.S. Army Air Corps and a Coast Guard officer) and received bachelor’s (Zoology), master’s (Aquatic Biology) and doctorate (Ornithology) degrees.

The new hire jumped into action and with Grobman grew the department. When Grobman left on sabbatical in 1959, Dickinson was named acting director. In 1961 Grobman decided not to return, and Dickinson was named director.

The Museum by then was bursting at the seams. Collections and staff had long outgrown the Seagle Building and Dickinson began earnestly working toward a new building. After clever negotiations he earned the University’s support and sited the new building in the pine forest next to the relatively new Zoology building. Dickinson reflects: “I was bound and determined to get us back on campus…I began to put together some ideas… I went to the administration and said I really need you to put a star on the campus map…and told them I wanted to tie in with the Zoology department… I got my star on the corner where it is now… I thought it was going to be an awful fight.”

A $1.1 million dollar grant from the National Science Foundation (then NSF’s largest museum construction grant) launched the project, and funds from the state, county, and city weighed in along with private funds. The drive to raise private funds was emboldened by a 1963 private gift for purchase of the Pearsall Collection of Native American Art. Dickinson recalls: “For the first time, the people in administration realized they could get private money. They never had done it before. And, oh goodness, Wayne [Reitz] told me one time it was just so much fun to go ask for money. It was a new experience.”

The new $2.3 million project was officially underway. Dickinson and colleague Walter Auffenberg had developed a building concept based on detailed space calculations, which as rendered by an art department colleague was a typical 1960s institutional structure. But Gov. Kirk appointed Jacksonville architect William Morgan to the job, and he created an award-winning design inspired by Florida’s ancient Native American mounds.

“Those were the days when building architects were part of the governor’s patronage…The next thing I knew Bill Morgan, the architect, walked into my office downtown and said “I’m Bill Morgan, I’m your architect.” I didn’t know Bill Morgan from nothing. Turned out we were lucky…He and I got on the train and went to Washington and saw the new [Smithsonian] wing…and the new state museum in Harrisburg…On the way home he was sketching on the back of an envelope and said “I’ve got an idea” …he had done a crude sketch of the building we built…I thought it was great.”

Staff and collections moved into the building in 1970, and the Museum was dedicated with fanfare in 1971. Today our exhibits and education functions have moved to Powell Hall, but Dickinson Hall is still the heart of the Museum, housing most of the collections and research staff.

J.C. Dickinson catapulted the Museum into the national limelight. His conviction that the Museum must grow to be great in both the research and education arenas, and his efforts to insert the Museum into national and international networks, have paid off. Now the largest collections-based museum south of the Smithsonian, and the largest university natural history museum in the country, our collections and research programs and our exhibits and education efforts are widely respected. As growth once again strains our available collections space, we have begun discussions about a new building, 100 years after that first move to campus. When I asked J.C. what he thinks about the Museum today, he replied, “We’re the best of our kind [university and state museum] in this hemisphere. I truly believe that.”

Darcie MacMahon is assistant director for exhibits at the Florida Museum of Natural History. An anthropologist by training, she has worked in the museum field for more than 25 years and at the Florida Museum since 1989.

Unless otherwise noted, photos from Florida Museum Archives.