On April 2, 2020, I began to worry that I needed more milkweed. I found three large monarch caterpillars in their fourth instar and several tiny caterpillars just in their second instar on our scraggly volunteer milkweed, which was decimated. I knew the littles weren’t going to make it, and maybe not even the big ones. Working from home and caring for my kids for over two weeks due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I had more time to closely observe the biodiversity in my yard, otherwise it may have been survival of the fittest for these garden friends.

I reached out to a colleague who works in the Florida Museum “Butterfly Rainforest” exhibit. Rainforest staff had been preparing for our Spring Plant Sale, one of our biggest plant sales and most popular events of the year. The plant sale had been postponed due to the Coronavirus, and staff members were dealing with an abundance of plants. I needed milkweed and they needed fewer plants to care for, so I was able to secure more food for these hungry little larvae.

Some of the plants came to me with tiny, almost microscopic, caterpillars and a few eggs on them, and over time, we ended up with 22 caterpillars! It became a project – a classroom – now that I was helping my children at home with their education, and a much-needed distraction of beauty and wonder during an unsettling pandemic.

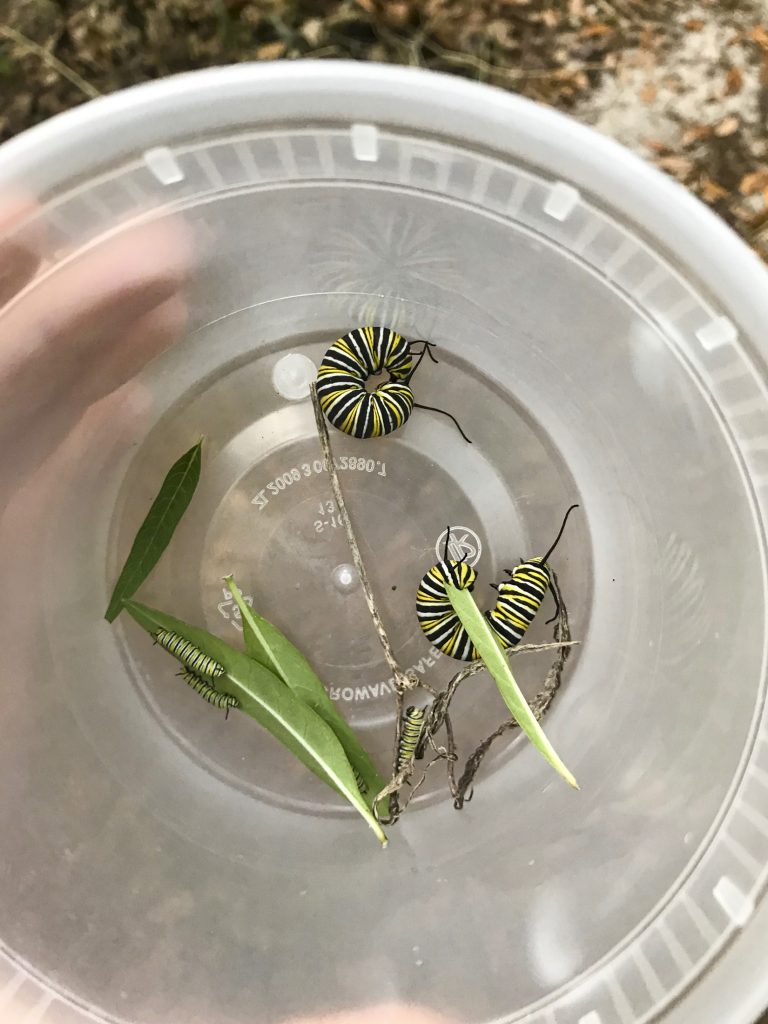

My daughters (ages 11 and 7) and I set the potted milkweed from the Museum on a table on our back patio. I went around to all the stripped milkweed in our yard and gathered all the caterpillars we could find. We placed them on the new milkweed and they began munching away.

Not long after, we noticed the biggest caterpillar crawling away. After several attempts to put it back on the milkweed we’d find it crawling away again. It was at this point we realized that it was crawling away because it was ready to pupate.

If we wanted to watch the whole process, we needed to somehow contain the caterpillars. After a little convincing, Ella, my oldest daughter, agreed to let us use her hanging bower as a makeshift butterfly house. This worked well.

Every day we checked on the caterpillars. My daughters made observations by counting and measuring caterpillars and taking notes as part of “science class.” We were excited that almost immediately the first caterpillar that kept crawling away pupated. Then the two other larger ones followed suit. We waited anxiously for butterflies and observed all the other little caterpillars grow fat and happy. My girls and I squealed with excitement when finding newly hatched itty-bitty caterpillars as we counted.

Unfortunately, the first butterfly never emerged from its chrysalis. We think it had “black death,” however the second emerged perfectly. This monarch would be our first to release.

Little did this butterfly know she would become an ambassador for monarchs, and she could not have picked a better time to emerge. She emerged on a Saturday afternoon, and the following day, Josie, my youngest, had a virtual Girl Scout meeting. She and I did a 30-minute monarch presentation.

I read a book on monarch butterflies to about seven Girl Scouts via Zoom, then shared our experience raising monarchs by showing the butterfly house we made, the many caterpillars and chrysalides we had and the butterfly. One caterpillar even began pupating, live, for all the girls to see!

The following weekend six or seven emerged.

There were five more chrysalides that looked ready Sunday. Then things got weird. We had a butterfly that never successfully emerged from its chrysalis, and three that emerged without legs. One was so severely deformed that it didn’t last more than a few hours. I held each of them, watched them struggle and sat with one as it died. My kids cried. The other two I helped eventually flew away. How long they lasted, I’m not certain.

This was not the first of the monarch drama. There were storms. We brought the hanging structure into the house and tucked away the plants that had caterpillars on them. One late evening my family of four huddled in one room with tornado alerts pinging our phones while the chrysalides hung safely in our foyer.

A day or two after releasing our first monarch, we had an adult visit our milkweed. (Had she returned?) At this point, most of our caterpillars had pupated, so I moved several of the milkweed plants out of the hanging bower.

We watched as she laid eggs.

A female monarch lays an egg on milkweed. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum

A female monarch lays an egg on milkweed. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum A monarch egg on a milkweed leaf. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum

A monarch egg on a milkweed leaf. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum Newly hatched monarch caterpillars are very small. They face many challenges of survival from food sources to environmental factors to parasites and diseases. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum

Newly hatched monarch caterpillars are very small. They face many challenges of survival from food sources to environmental factors to parasites and diseases. Kristen Grace/Florida Museum

A few days later we found 12 more tiny monarch caterpillars, and I asked myself “Do I do this again?” I decided to just observe these caterpillars in the garden and turned my focus back to the ones in the bower.

After the lot with the missing limbs there were five chrysalides remaining. I was so nervous and couldn’t help but think that the rest of the butterflies would have issues. To my relief, they all emerged normally.

Friday, May 8, two days before Mother’s Day, our last chrysalis finally looked ready to emerge. I watched it for 12 hours with my camera in an attempt to capture the emergence on video. This pupa was on a potted milkweed, so I was able to bring the plant inside and control the environment to get good footage. I watched and waited until 11:30 p.m. when it finally emerged, and on camera!

After the butterfly emerged, I put it and the plant back in the bower to release the next day. I wanted my girls to be a part of the culmination of this accidental five-week project. Saturday morning was beautiful. We released the monarch, a male, and wished him well on his new journey as an adult butterfly.

It was bittersweet, but at least I still have a couple of caterpillars crawling on the recovering milkweed in our garden.

A lepidopterist at the Museum informed me the monarch survival rate in the wild is 2% to 4%. We had 22 and released 20.That is a very satisfying survival rate well over 80%.

In many ways, this journey could not have been better timed. It has opened doors to conversations about science, nature, life and death with my children. I watched them study these insects with curiosity, and witnessed their joy in interacting with and releasing these amazing butterflies. Pandemic or not, children or not, I recommend rearing butterflies at least once in your lifetime.

###

The Florida Museum Plant Sales often have milkweed available for purchase. Visit the Plant Sale website for plant and purchasing options.