In 1831, John James Audubon (1785-1851) arrived in Florida to collect water birds for the third volume of his great illustrated book, Birds of America. After disembarking at St. Augustine on November 20, he traveled on foot and by pony over log roads and trails.

Audubon explored the east coast of Florida and the Florida Keys for the next six months. He followed the waterways by canoe, skiff, cutter, and schooner, and the mosquitoes followed him. “Reader,” he wrote, “if you have not been in such a place, you cannot easily conceive the torments we endured.”

Audubon was born on April 26, 1785, at Les Cayes, Santo Domingo. His father was an affluent French sea captain and planter; his mother was a Creole. His father’s French wife raised young Audubon in France, but despite later claims, he received little formal education. From 1803 to 1805, the youth lived on his father’s estate outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After a brief sojourn in France, Audubon returned to the United States and operated a lead mine near Philadelphia.

In 1808, Audubon married Lucy Bakewell. The couple moved to Kentucky, where Audubon operated stores in the frontier towns of Louisville and Henderson. An unsuccessful merchant, he began drawing birds. In 1819, his ill-advised grist mill and lumber operation failed. From 1819 to 1826, Audubon made ends meet as an itinerant portrait painter throughout the Mississippi river valley, a taxidermist in Cincinnati, Ohio, and a drawing teacher in New Orleans and St. Francisville, Louisiana. An accomplished fiddler and lady’s man, he also gave dancing lessons. While he traveled, wife Lucy worked as a governess to support their two sons, Victor and John.

A chance meeting with the pioneering American ornithologist Alexander Wilson in Kentucky gave Audubon confidence in his abilities to draw birds, and, in 1820, he decided to undertake a massive publishing project, life-size illustrations of the birds of America. He spent the next six years seeking support, but meeting little encouragement. took his project to Great Britain. After 1826, he procured publishers, first in Scotland and then in England capable of printing large enough plates. While the monumental Birds of America was in production, Audubon traveled as a celebrity throughout Europe and sold $1,000 subscriptions to his book. He also made several trips to the United States.

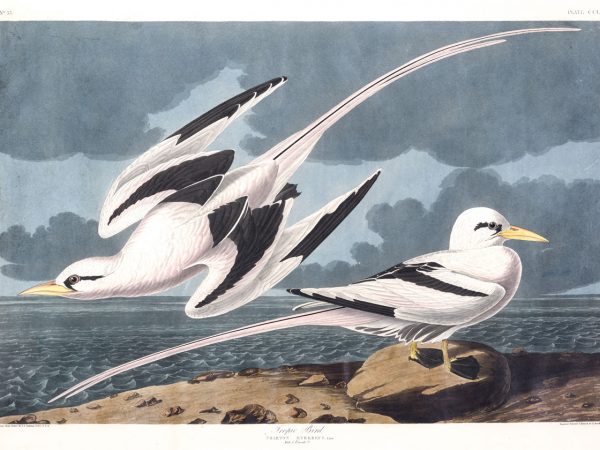

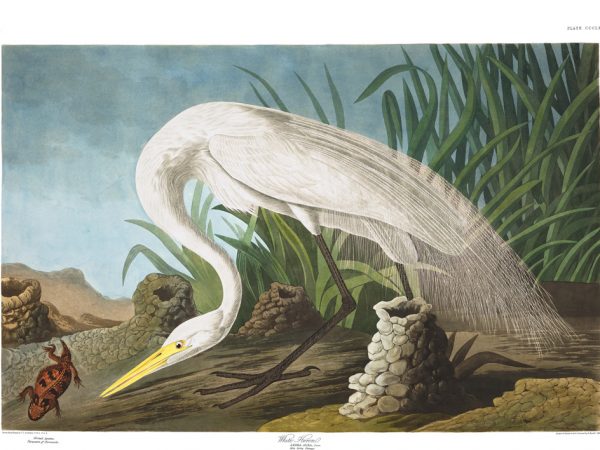

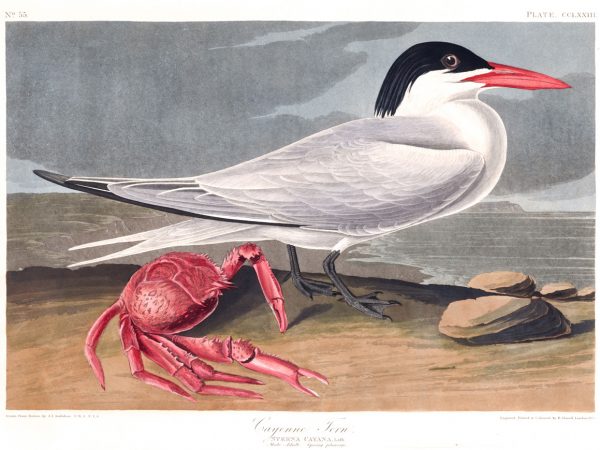

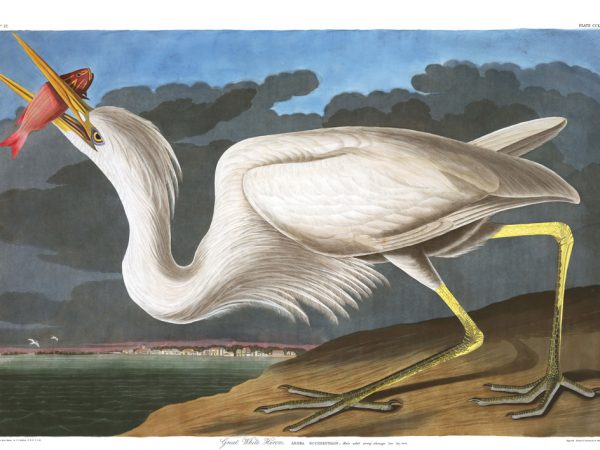

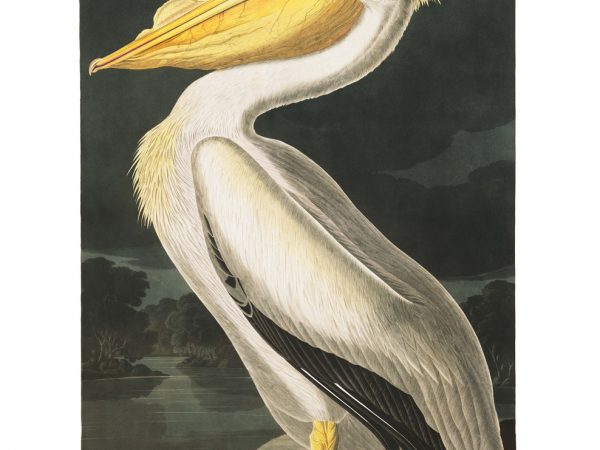

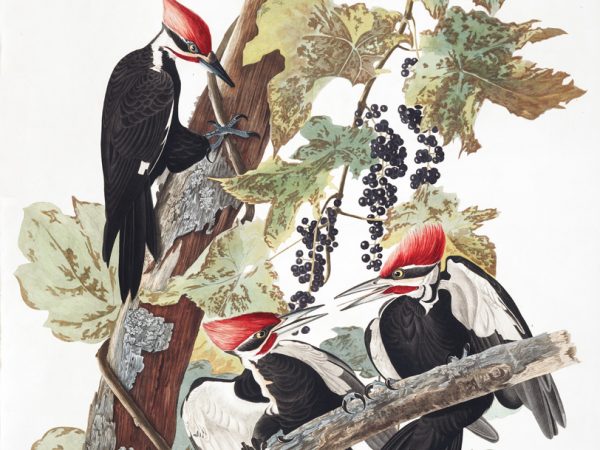

Audubon explored the Middle Atlantic states in 1829; two years later, he explored the Southeast to the Florida Keys. After he left Florida in 1832, Audubon continued north to Labrador and west to Texas to search for new birds for his last volumes. Birds of America was literally the biggest bird book the world had ever seen. Audubon portrayed 1065 birds, representing 489 species. The 435 magnificent engravings made from his watercolor drawings show birds life-size in natural habitats. Edge to edge, the grand elephant folio plates would paper one quarter of a mile.

The large and elaborate illustrations required the talents of more than one artist. Audubon first drew his specimens in watercolor. Joseph Mason, a gifted young painter whom Audubon met in 1820, provided the floral details which give many of the plates their grace. In Florida, George Lehman, a professional Swiss landscape artist accompanied Audubon. Lehman also composed one of the finest Florida plates, plate 321, which shows the “beautiful and singular” roseate spoonbill. Other details for later plates were the work of Maria Martin, the sister-in-law of Audubon’s later collaborator, the Reverend John Bachman, whose two daughters married Audubon’s sons.

Audubon’s hand-colored illustrations are beautiful, but are they “Drawn from Nature” as claimed on the bottom of each plate? In fact, Audubon and other nineteenth-century bird artists did not draw living birds. They sketched mounted birdskins. Audubon preferred to wire recently shot birds in life-like positions and to draw them immediately. To create the illusion of flight, he hung birds upside down so that the wings opened. He did not keep these specimens.

In Florida, Audubon discovered 52 types of birds new to him. His letters home and other published writings also recorded the scenery, settlements, and colorful inhabitants. Some of these descriptions were published in his Ornithological Biography, and several of his bird plates illustrated frontier conditions.

Despite troubles with Creeks and Seminoles, in 1831, Florida was enjoying a period of peace from oversea invasion, and plate 269 showed the old Spanish cannon lying unused on the beach below the Castillo de San Marco in St. Augustine. Audubon, however, did not enjoy his stay in this lovely old city. “St. Augustine,” Audubon wrote Lucy on November 23, 1831, “resembles some old French village” with “streets about 10 feet wide and deeply sanded.”

Audubon boarded at a tavern for $4.50 a week. Although he dined upon “hare, fish and venison” three times a day, he complained about the company, “principally poor Fisherman,” and he grumbled about supplies: “I wish thee to forward me,” he wrote his wife, “some good socks…the salt marshes through which I am forced to wade every day are the ruin of everything.”

Although timber on public land was reserved for the United States Navy, the federal government was unable to police cutting in Florida. The timber thieves, whom Audubon called “live-oakers,” came from the northeastern states during the winter months and cut down live oaks like those shown in plate 247, the “Hooping” crane. Audubon’s humor was more consistent than his spelling. “Their provisions,” he wrote with some envy, “consist of beef, pork, potatoes, biscuit, flour, rice, and fish together with excellent whiskey.”

“This is the way in which we spend the day,” Audubon reported of his Florida work in 1831. “We get into a boat, and after an hour of hard rowing, we find ourselves in the middle of most extensive marshes, as far as the eye can reach. The boat is anchored, and we go wading through mud and water, amid myriads of sand-flies and mosquitoes, shooting here and there a bird.” Audubon wanted to hire some helpers, but the “residents of St. Augustine,” he found were “all too leazy [sic] to work, or if they work,” their high prices “put it out of the question to employ them.” Plate 387, the glossy ibis, shows the simple wooden buildings and split-rail fences typical of the surrounding countryside.

By late winter, grey wetland Florida had defeated Audubon’s spirit: “We are surrounded by thousands of Alligators and I dare not suffer my…good Newfoundland Dog Plato to go in the River.” Disappointed, he returned to Charleston, South Carolina, but decided to give Florida a second chance. Audubon by now was a celebrity, the “American Woodsman,” and the federal government assisted his efforts with sea passage to the Florida Keys on the U.S. Cutter Marion.

Audubon arrived in the Florida Keys in late April of 1832. As the Marion approached safe harbor at Indian Key, Audubon recalled that his “heart swelled with uncontrollable delight.” “The air,” he wrote Lucy, “was darkened by whistling wings.” Audubon’s enthusiasm was contagious, and he collected liberally with the aid of a pilot, cook, and “sturdy crew” armed with guns. The “mass of birds” obtained, Audubon boasted, looked like a “small haycock.” On Sandy Key, nests were so numerous that “ere long we had a heap of eggs that promised delicious food.”

Although Audubon was a worldly man who desired fame and fortune, in Florida, he found himself “increasingly amazed at the appearance of things.”

Audubon certainly viewed nature with the eye of an artist, but was he a true naturalist or simply an opportunist? In 1827, Noah Webster published the first American dictionary. That very same year, Audubon published the first volume of his spectacular bird book. Both works reflected American interest in words, in Audubon’s case, new names for new species-as well as news, numbers, and lists of all kinds.

Audubon was a gifted writer, and his adventures recounted in his Ornithological Biography appeased a reading public eager for exciting books by Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper. But was Audubon’s art good science? During his lifetime, some naturalists criticized his illustrations as too “flamboyant” for science, too “unrestrained and painterly.”

In his eagerness, Audubon was bound to make mistakes; for example, his illustration of mockingbirds shows a rattlesnake attacking the nest. Rattlers, his critics correctly claimed, do not climb trees, and furthermore, they do not feed on bird eggs. Poor preservation techniques also compromised Audubon’s ability to save specimens as proof of his finds. Cleaning birds in the hot Florida sun and storing them without the benefit of refrigeration were not pleasant tasks, and Audubon was not able to save his specimens for others to examine and substantiate his claims. Furthermore, some species of North American birds were becoming scarce in Audubon’s time.

There were no laws protecting endangered species. Too the contrary, laws mandated the destruction of agricultural pests. Songbirds were commonly sold in city markets for food. Although Audubon, a good marksman, enjoyed shooting birds, he also strove to create a public awareness of birds. His reputation, if not his hardworking wife’s household accounts, benefited from this attention.

Retiring to New York, Audubon built a comfortable house called “Minnie’s Land” on the banks of the Hudson River. Done with birds, he began a major illustrated work on North American mammals with the help of his two sons. When Audubon died in 1851, a reporter for Harper’s Magazine remarked that Audubon had “linked himself with the undyingness of nature.” Today Audubon’s name is linked with the conservation movement through the society that bears his name.

Does Audubon deserve this association? Audubon published the first volume of his Birds of America at just the time when Andrew Jackson was successfully campaigning for the presidency of the United States. Under Jackson, the earlier ideal of preserving a virtuous republic gave way to the ideal of preserving individual opportunity and ensuring that the United States would remain a nation of self-made men. A self-made man like Jackson, Audubon quite literally embodied the Jacksonian ideal. When an artist friend, John Vanderlyn, painted a famous full-length portrait of Jackson he drew the Indian fighter’s face from life, but persuaded Audubon to model for the body. Like Jackson, Audubon mastered the politics of opportunity. In Florida, he did not hesitate to purchase natural history specimens from “wreckers,” men lured ships onto rocky reefs to salvage their cargos.

In the mid-nineteenth century, wildlife was abundant: “there are so many birds they will never be missed, any more than mosquitoes!” By the 1880’s, observers noted dramatic decreases in the numbers of small birds. Birds of all sizes had become targets of plume hunters. Feathers from orioles and warblers to herons, sandpipers, and even crows appeared on fashionable ladies’ hats.

“Nearly all the ladies wear bird skins or heads or wings,” wrote Dr. George Bird Grinnell, an ornithologist who published Field & Stream Magazine in New York. Grinnell was especially concerned that trade in egret feathers was exterminating whole populations in south Florida.

In February 1886, Grinnell spearheaded an organization for the protection of birds: “The land which produced the painter naturalist John James Audubon will not willingly see the beautiful forms he loved so well exterminated.” Florida bird populations were the focus.

By August 1886, 11,000 members had pledged not to harm birds, destroy eggs or nests, or “make use of feathers for dress or ornament.” By February 1887, one year after its founding, the Audubon Society had 39,000 members. In April, Dr. Grinnell published the first issue of The Audubon Magazine. The magazine’s contents included articles on the life and works of John James Audubon, natural histories of birds, stories for young readers, and an occasional lecture such as “Man the Destroyer” on extinction, a poorly understood concept.

A woman from Boston published a brave article with the title “Woman’s Heartlessness.” “When the Audubon Society was first organized,” she confessed, “we flattered ourselves that the tender and compassionate heart of woman would at once respond to the appeal for mercy. But after many months of effort, we are obliged to acknowledge ourselves mistaken … Not one in fifty is found willing to remove at once the birds from her … hideous headgear.”

“Flit, sand piper,” she warned, “from the sea’s margin to some loneliness remote and safe from the noble race of man! Year after year you come back to make your nest in the place you know and love, but you shall not live your humble, blissful, dutiful life, you shall not guard your treasured home, nor rejoice when your little ones break the silence with their first cry to your for food. You shall not shelter and protect and care for them with the same divine instinct you share with human mothers. No, some woman wants your corpse to wear on her head!…Yet how refreshing is the sight of the birdless bonnet!”

Thanks to early voices of outrage, today, the Audubon Society is one of the largest private conservation organizations in the world.

Click on any link below to listen the recording.

Representative Paintings by John James Audubon by Dr. John Hardy (6:08)

All images below via the National Audubon Society.

Image Gallery

As you travel, enjoy these images in museums throughout the United States.

All images below via the National Audubon Society.

via Audubon Society

via Audubon Society