Although Nuttall, Say, and Peale disengaged their science from Romanticism, their public continued to picture them as Romantic figures exploring Romantic spaces. In 1831, a reviewer noted with obvious disappointment that Audubon described only one dangerous episode, and that the earlier ornithologist, Wilson, did not “tell us of any danger of life or limb encountered – except on one occasion and then it was but a dream.”1

In truth, unlike Estwick Evans, their contemporary from New Hampshire, these naturalists did not don buffalo robes to experience the American wilds.2 They did not welcome pathlessness; rather, later in their careers, they joined military surveys mapping the West.3 They were not seeking primitivism outside the city settings in which they grew up and to which they would return; nor were they anticipating spiritual sanctuary. To the contrary, their purposes were scientific.

Uninterested in developing Romantic themes, what did exploring naturalists hope to accomplish with their frontier descriptions? Recording unknown geography was certainty consistent with their task of scientific observation and collection. Moreover, they were interested in the impact of white settlement upon frontier landscapes, distribution of species, and welfare of Indian peoples.4 Popularizing these ideas was difficult because the full biological meaning of survival and extinction was unclear in the decades before the publication of Charles Darwin’s ideas about the origin of species by natural selection.5

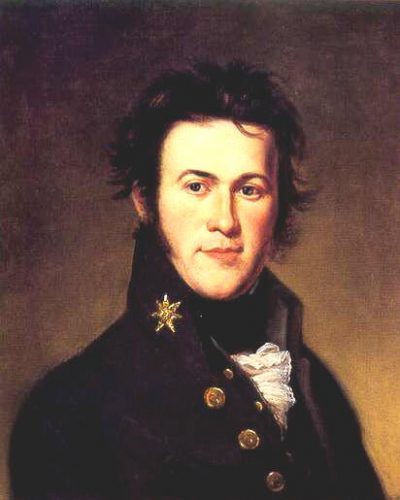

The handsome figure of Alexander Wilson best fulfilled Romantic expectations for the American naturalist. One reviewer speculated that had Wilson lived beyond 1813, “his original genius” and his opportunities to wander might have made him “like Wordsworth’s Peddlar, a good Moral Philosopher.”6 This insertion of Wilson, himself Poet, into the landscape of British Romantic poetry was not whimsical, even if subsequent Philadelphia naturalists were intellectually uncomfortable in the same terrain. Wordsworth had been impressed with Bartram’s Travels. The Youth from Georgia’s shore” in Wordworth’s poem “Ruth” owes much to Bartram’s descriptions of lush southern flora.7

He told of the magnolia, spread

High as a cloud, high overhead!

The cypress and her spire;

-Of flowers that with one scarlet gleam

Cover a hundred leagues, and seem

To set the hills on fire.

A year after Wilson’s much publicized death, Wordsworth may well have had Bartram’s great protege in mind when he composed “The Excursion,” the poem in which the Peddlar appeared.

Given Wilson’s popularity and esteem, one may well wonder how nineteenth-century natural history remained free of the Romanticism part of the American intellectual response to nature from William Cullen Bryant to Henry David Thoreau. Bartram’s relative, Thomas Say certainly seemed “to wander with an easy mind,” to use a phrase from Wordsworth, but casual disregard for frontier surroundings was not what readers expected.

Critics recognized that naturalists learned much from their frontier experiences. They agreed that their published passages were “all excellent – and some sublime.” Yet, they missed the sense of sustained elevation and physical involvement found in Bartram’s Travels.