During the first half of the nineteenth century, the observations of naturalists such as the Bartrams, Titian Ramsay Peale, Thomas Say, and John James Audubon made Florida a destination point for those interested in outdoor recreation-hunting, fishing, and bird-watching.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the natural beauty of Florida attracted real estate developers, railroad magnates, artists, photographers, game hunters, sports fishermen, naturalists, and their wives. After the Civil War, tourists traveled to see the natural sights, especially the springs, in steamboats, buggies, and railways. Natural history was part of their expectations.

Commercial image-making was important to the early success of Florida tourism. Real-estate developers invited well-known photographers to take pictures of their hotels to attract tourists. Artists, enjoying the tourist trade, sought the patronage of developers and also helped them design tourist attractions.

Distant publishers, many in mid-western cities, printed photographic images of Florida. To meet the needs of tourism, the United States Post Office permitted a new mailing piece called the penny postcard. Many hand-colored postcards have become collector’s items.

Published in such national magazines as Harper’s, photos became promotional media for Florida.

Another offshoot of black and white photography were penny postcards, especially hand-colored postcards. Printed in a useful format, postcards became popular tourist souvenirs, sent to relatives and friends around the world with that famous remark, “wish you were here.”

In the print shops, workers, (many immigrants from Central Europe) who had never been to Florida, selected the bright colors and omitted both insects and shadows in these durable images of the Sunshine State. Ironically, many of these postcards show introduced species, such as orange trees, banyan trees, and camellias.

One of the most famous photographers in Florida was William H. Jackson (1843-1942), a veteran photographer of the government surveys of the western territories, especially of the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone. Jackson’s photographs of Yellowstone, taken in 1871, were largely responsible for the establishment of the national park.

Jackson’s camera opened new vistas of the American frontier, and he hauled 100 lbs of equipment to get this view of Mount of the Holy Cross, one of Jackson’s most famous photographs, taken in Eagle County, Colorado, in 1873. This image secured his national reputation and made landscape photography into a viable commercial enterprise.

After the Colombian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1892, Jackson began photographing northeastern Florida for a Detroit postcard company. He later changed careers and spent the second half of his long life as a landscape painter and muralist of public buildings in Washington, D.C.

Besides photographic images, other important considerations in the development of Florida nature tourism were:

- Game hunting, including ‘gator wrassling

- Fishing

- Plume hunting for hats

- Captive birds, especially pet mocking birds

- Springs with benefits of hydrotherapy

- Railroads

- Steamboat traffic

- Citrus groves

- Archaeological pursuits

- Hotels

Hotels, some with artist’s studios, photographic dark rooms, swimming facilities, and tennis courts, marked tourists’ inroads in northeastern Florida.

Image Gallery

Images obtained from the State Library and Archives of Florida.

Jessie Dakin, pole fishing along the railroad tracks, Georgetown, 1888, in a photograph taken by her husband, Leonard Dakin. Note the rowboats and different attire of the two men with Mrs. Dakin. The houses across the St. John’s River are large estates.

Jessie Dakin, pole fishing along the railroad tracks, Georgetown, 1888, in a photograph taken by her husband, Leonard Dakin. Note the rowboats and different attire of the two men with Mrs. Dakin. The houses across the St. John’s River are large estates.

Tea Time under a live oak tree draped with Spanish moss in Racemo, 1887. In this photograph, taken by Leonard Dakin, a pet dog joins George Dakin, his wife Anne Maria, and daughter Florence as they take tea outdoors on a table set with a linen cloth.

Tea Time under a live oak tree draped with Spanish moss in Racemo, 1887. In this photograph, taken by Leonard Dakin, a pet dog joins George Dakin, his wife Anne Maria, and daughter Florence as they take tea outdoors on a table set with a linen cloth.

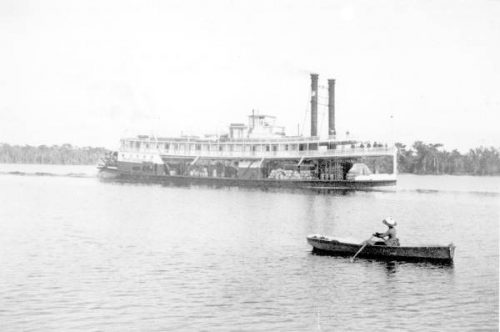

In this photo taken off Racemo in 1888 by Leonard Dakin, the steamboat “Chattahoochee” travels upriver, or to the north, to Jacksonville and passes the athletic Mrs. Dakin rowing on the St Johns River.

In this photo taken off Racemo in 1888 by Leonard Dakin, the steamboat “Chattahoochee” travels upriver, or to the north, to Jacksonville and passes the athletic Mrs. Dakin rowing on the St Johns River.

Businessmen exchange news on the dock in Jacksonville. Stopping at landings upriver, local steamers like this one, carried housewares, lumber, and farm animals on the first deck and passengers on the upper deck.

Businessmen exchange news on the dock in Jacksonville. Stopping at landings upriver, local steamers like this one, carried housewares, lumber, and farm animals on the first deck and passengers on the upper deck.

A photograph attributed to C. Seaver, Jr., c. 1873 shows the home in Mandarin, Florida, of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-96), author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Here she sits with her husband and daughters. Steamers carried crowds of visitors to this house, situated within shouting distance of the landing pier. In 1873, Mrs. Stowe published Palmetto Leaves, a book of letters to women friends about her life in north Florida.

A photograph attributed to C. Seaver, Jr., c. 1873 shows the home in Mandarin, Florida, of Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-96), author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Here she sits with her husband and daughters. Steamers carried crowds of visitors to this house, situated within shouting distance of the landing pier. In 1873, Mrs. Stowe published Palmetto Leaves, a book of letters to women friends about her life in north Florida.

Two women swing in a hammock as they enjoy leisure time at the Magnolia Springs Hotel, 1891, in this photograph by O. Pierre Havens. Note the river landing. Visitors arrived by steamboat on the St Johns River or via railroad from Jacksonville (28 miles to the north). Hotel rates were $6.00 a day with meals. This hotel boasted an early dark room for photographers and tennis courts, later used for tournaments.

Gail Borden’s Home and Park, Green Cove Springs, 1892. Five years earlier, John G. Borden, founder of “Borden’s Milk” (at first, a condensed milk product) purchased 400 acres around the springs, which he landscaped with parks, courts, and drives.

Gail Borden’s Home and Park, Green Cove Springs, 1892. Five years earlier, John G. Borden, founder of “Borden’s Milk” (at first, a condensed milk product) purchased 400 acres around the springs, which he landscaped with parks, courts, and drives.

Spring Bath Houses, Green Cove Springs, c. 1874. Steaming up the St Johns River from Jacksonville, tourists stopped to bathe at the springs and dine at the nearby Clarendon Hotel or its rival, the Palmetto House.

Spring Bath Houses, Green Cove Springs, c. 1874. Steaming up the St Johns River from Jacksonville, tourists stopped to bathe at the springs and dine at the nearby Clarendon Hotel or its rival, the Palmetto House.

Men’s Time in the Pool, Green Cove Springs, April 3, 1883. Gone are the simpler facilities of earlier decades. These gents, wearing their birthday suits, have paid 25 cents to swim in the improved spring pool, an area 25 x 60 ft and 4 ft deep. Men and women used the pool at different hours.

Two men wait in a large and comfortable rowboat near Astor (Alexander Spring Run) on the St Johns River, perhaps to ferry in tourists from a river steamer to the beautiful Alexander Springs, now the site of a state park. This photo was taken in February of 1896.

Waterfront, Palatka, 1892. A crowded excursion boat leaves the dock for Silver Springs, the last stop on the Ocklawaha River. Before the Civil War, fallen logs, low limbs, and floating plants made the Ocklawaha impassable beyond Silver Springs.

The St Johns Hotel, c. 1873, in a photograph by Rufus Morgan. This small hotel in Palatka charged guests $3.50 a day. Look closely: the men standing below with their wives crowded in the balcony above have come to visit Silver Springs.

Although mounted bands of rowdies frequently disturbed the peace in this frontier town, by 1870, Palatka could boast a band of sorts, and

The popular tourist spot of Palatka boasted wedding facilities at two hotels and two churches, as well as two steam mills, two sawmills, horse-drawn streetcars, and a newspaper named the Florida Rambler, happy to run announcements and ads for all from 1873-75.

In a word, Palatka was a tourist trap, the gateway town for travelers from the St. Johns River to springs in central Florida and for hunters. In this photograph by Irving Haas, at Heiss’s Old Curiosity Shop, c. 1875, everything, including the “Centennial” alligator, was for sale. The place was literally filled with living and dead animals, stuffed specimens, and odd body parts.

Here folks gathered round the front of a shell shop for a photo op, along with a trophy ‘gator. This group, including many well-dressed children, look fresh and crisp and may have just arrived on a steamer for a Florida outing.

The steamer Astatula navigates the narrows of the Ocklawaha River in this 1893 photograph by Jonas G. Mangold. Leaving Palatka at 10 o’clock in the morning, tourists to Silver Springs made a memorable river trip of some 100 miles before entering the famous 8-mile spring run. They returned to Palatka by train.

Steaming on the Ocklawaha River in smaller often overloaded vessels, tourists were literally face to face with nature.

One tourist to Silver Springs wrote: “innumerable paraquets, alarmed at our intrusion scream out their fierce indignation, and then, flying away flash upon our admiring eyes their green and golden plumage.” These birds, illustrated by John James Audubon (1785-1851) in his great book, Birds of America, were the now extinct Carolina parakeet.

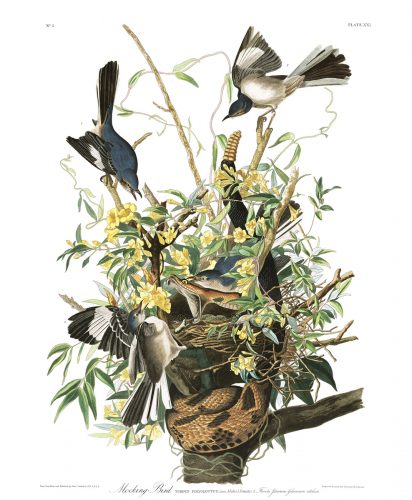

The garrulous mockingbird, state bird of Florida, illustrated here by John James Audubon, was popular among tourists, in part because of Audubon’s famous image of the birds attacked by a rattlesnake. In 1875, the price for live mockingbirds in Jacksonville ranged from $10 to $500, depending upon how good a mocker the bird proved to be.

As tourist steamers approached Silver Springs, they left the muddy waters of the Ocklawaha and entered the clear waters of Silver River, an upside-down world, in a detail of a ca.1888 photograph attributed to William H. Jackson, an influential photographer of the American West.

As tourist steamers approached Silver Springs, they left the muddy waters of the Ocklawaha and entered the clear waters of Silver River, an upside-down world, in a detail of a ca.1888 photograph attributed to William H. Jackson, an influential photographer of the American West.

Tourists who arrived by train could stay at the conveniently located Silver Springs Hotel, shown here in a 1886 photograph by Stanley J. Morrow. A state-of-the-art hotel, fitted out with gas lights and Thomas Edison’s newly invented electrical call bells, opened on January 25, 1886. Guests also enjoyed the musical orchestra and day trips by stage to Ocala and Gainesville.

This view of the Great Sink, or Disappearing Lake, just south of Gainesville, photographed ca.1902, shows the north rim of present-day Paynes Prairie State Preserve, located south of Gainesville in Alachua County. In 1774, the naturalist William Bartram (1739-1823)visited this great sinkhole as a guest of the Creek mico, Cowkeeper, whose people resided in the adjacent area then known as the Alachua Savanna. Note the photographer at work in the lower right and raised camp beds covered with mosquito nets in the center.

This view of the Great Sink, or Disappearing Lake, just south of Gainesville, photographed ca.1902, shows the north rim of present-day Paynes Prairie State Preserve, located south of Gainesville in Alachua County. In 1774, the naturalist William Bartram (1739-1823)visited this great sinkhole as a guest of the Creek mico, Cowkeeper, whose people resided in the adjacent area then known as the Alachua Savanna. Note the photographer at work in the lower right and raised camp beds covered with mosquito nets in the center.

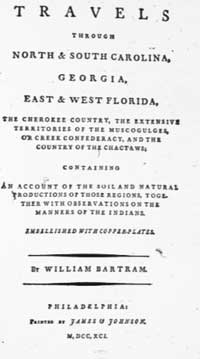

The naturalist, William Bartram, for whom Bartram Hall at the University of Florida is named, published the first description of the Alachua Savanna in 1791 in his famous book of Travels.

The naturalist, William Bartram, for whom Bartram Hall at the University of Florida is named, published the first description of the Alachua Savanna in 1791 in his famous book of Travels.

This map of the St Augustine region published in William Bartram’s book of Travels and his route from the Carolinas, south through Georgia to North Florida beckoned many later naturalists and artists, from Titian Ramsay Peale and Thomas Say to John James Audubon and John Muir.

This map of the St Augustine region published in William Bartram’s book of Travels and his route from the Carolinas, south through Georgia to North Florida beckoned many later naturalists and artists, from Titian Ramsay Peale and Thomas Say to John James Audubon and John Muir.

For late nineteenth-century travelers along the St Johns River, side trips were possible. A photograph taken near Barberville, ca.1890, by William Henry Jackson, shows one of many beautiful spring runs, rich with birds and other wildlife. John James Audubon visited nearby Spring Garden and the Bulow Plantation in 1831 to collect specimens for his Birds of America.

The steamer Marion, with Captain Gray, approaches Iola Landing, on Ocklawaha River, ca.1875, in a photograph by Jerome N. Wilson. Small tourist steamers, no wider than 21 feet, could travel beyond Silver Springs up the Ocklawaha as far as Orange Springs, in present-day Marion County. Crowded and cramped as the quarters were on board, many ventured overnight passage. In May of 1874, the poet, Sidney Lanier (1842-81) booked overnight passage on the steamer Marion to Silver Springs. In 1875, in Florida: Its Scenery, Climate, and History, he wrote that he awoke next morning and felt “as new as Adam.”

The steamer Marion, with Captain Gray, approaches Iola Landing, on Ocklawaha River, ca.1875, in a photograph by Jerome N. Wilson. Small tourist steamers, no wider than 21 feet, could travel beyond Silver Springs up the Ocklawaha as far as Orange Springs, in present-day Marion County. Crowded and cramped as the quarters were on board, many ventured overnight passage. In May of 1874, the poet, Sidney Lanier (1842-81) booked overnight passage on the steamer Marion to Silver Springs. In 1875, in Florida: Its Scenery, Climate, and History, he wrote that he awoke next morning and felt “as new as Adam.”

In 1875, Sidney Lanier’s book about Florida included many fine illustrations, including a picture of the Alachua Sink, or Great Sink in Payne’s Prairie. Lanier was a Confederate veteran, whose identification with the South and Reconstruction recommended his descriptions of Florida’s natural beauty to many readers.

Lanier also had training in natural history. Before the Civil War, he attended Oglethorpe University in Midway, Georgia, where he met Professor James Woodrow, a student of the great naturalist, Louis Agassiz (1807-73) at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Mass.

Louis Agassiz adamantly opposed Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, but Woodrow’s views on evolution, influenced also by German Romanticism, made a lasting impression upon the poetic Lanier. Interesting enough, an important collection of Louis Agassiz’s books have been transferred to Special Collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, at the University of Florida.

Captain Rise navigates the Okahumkee to Fort Brooke on the Ocklawaha River, April 17, 1876, photograph by Jerome N. Wilson and O. Pierre Havens. Fort Brooke, settled by small land holders displaced by the Civil War, had been the site of a Seminole attack in March of 1841. This landing, about 2 miles below Orange Springs, had a sulfur spring, but no accommodations. From Orange Springs, the end of the line, adventuresome tourists took a pole-barge with the mail up Orange Creek to Orange Lake in present-day Marion County.

Tourists enjoyed miles of fragrant orange groves, here at the unidentified community of Seville, in a ca.1890 photograph by William Henry Jackson

Tourists enjoyed miles of fragrant orange groves, here at the unidentified community of Seville, in a ca.1890 photograph by William Henry Jackson

Photographers could not resist posed pictures like this Message Box at Sharpe’s Ferry, ca. 1875, photograph by Jerome N. Wilson. “Swampers” like this man left letters in the cigar box nailed to a tree for any passerby to take to town. Many tourists enjoyed these rustic touches.

Photographers could not resist posed pictures like this Message Box at Sharpe’s Ferry, ca. 1875, photograph by Jerome N. Wilson. “Swampers” like this man left letters in the cigar box nailed to a tree for any passerby to take to town. Many tourists enjoyed these rustic touches.

ID Spring, ca.1895, photograph by J. A. Enseminger. Note the unusual hemmed garments of some members of this excursion party, posed like a Winslow Homer painting. Travelers arriving at Live Oak or Wellborn by rail took a daily stage to springs along the Suwannee River.

ID Spring, ca.1895, photograph by J. A. Enseminger. Note the unusual hemmed garments of some members of this excursion party, posed like a Winslow Homer painting. Travelers arriving at Live Oak or Wellborn by rail took a daily stage to springs along the Suwannee River.

In Gainesville, Civil War veterans posed for an unidentified group portrait.

In Gainesville, Civil War veterans posed for an unidentified group portrait.

Survivors of yellow fever, a real killer in dirty military camps of the South, were glad to be alive.

Survivors of yellow fever, a real killer in dirty military camps of the South, were glad to be alive.

Waters from Paynes Prairie drain into the Great Sink of Bartram’s Alachua Savanna and travel through porous limestone underground to the Suwannee River.

Bartram’s Alachua Savanna, Paynes Prairie, shown here in dry conditions, as a landscape of flowers with a resident population of sandhill cranes.

Bartram’s Alachua Savanna, Paynes Prairie, shown here in dry conditions, as a landscape of flowers with a resident population of sandhill cranes.