Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos) Project

Going on 10 breeding seasons of 2005-2014 and continuing we have studied different aspect of the incubation and nestling phase of the Northern Mockingbird. Our study site is at the University of Florida campus, and during these breeding seasons we captured and color banded more than 400 adult birds and more than 1000 nestlings. We also monitored more than 700 nests. We used data loggers to measure time on the nest and conducted direct observation to estimate nestling feeding rates by the adult birds. The Northern mockingbird is a species where only the female incubate (male does not provision food while the female is on the nest) and both parents feed the nestlings. Mockingbird clutch size can varied between 2 and 5 eggs but the average is three. We want to thank D. DeSantis, J. Jankowski, W. Schelsky. and A Savage, for helping with data collection during the first two breeding seasons. Find out more below.

Mockingbird Field Crew 2009

Mockingbird Field Crew 2006-2008

Effect of food availability and temperature on incubation behavior

Avian incubation behavior is thought to be influenced mainly by ambient temperature and food availability. Field studies, however, have generated contradictory results and no general agreement about the relative importance of food and temperature influence and on how different components of incubation behavior are affected by each. To date, no studies have manipulated both food availability and temperature in a controlled experiment, which has made it impossible to assess any interaction among these variables. Therefore, we experimentally increased both food availability and ambient temperature during incubation in the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos). Our results demonstrated that both food availability and temperature influence incubation behavior. Increasing food availability enabled females to spend more time on the nest and in self-maintenance activities when off the nest. Increasing heat caused females to spend less time on the nest and to make more trips to and from the nest. When both food and temperature were increased, their effects on incubation time offset each other. These changes in incubation patterns had little effect on fitness, although embryo mass was lowest in the treatment in which only heat was increased, suggesting that heat may stress embryos, but not when extra food is also provided. Perhaps the reason why previous studies present contradictory results is because food and temperature offset each other in complex ways that could obscure their effects on incubation behavior. Indeed, our experiment shows that food and temperature both affect avian incubation behavior, but that different tradeoffs apply to each environmental factor. Londoño et al in press

Behavioral decision throughout the breeding season

The Northern Mockingbird experience a long breeding season on our field site. The breeding season begin late February and ends late July. There are two main factors that change during this long breeding season, ambient temperature and rain fall. Ambient temperature and rain fall increases as the breeding progress. Throughout the breeding season individual female can have up to five nesting attempts (if nest are prey upon) and up to two nesting attempts if individual females are successful. Usually re-nesting takes more than two weeks, during this time environmental variables can change significantly. This means that females have to make reproductive decision to adjust their energy investment according to the new environmental condition. We investigate change on Clutch size, egg mass, and nest mass, incubation behavior and female body mass.

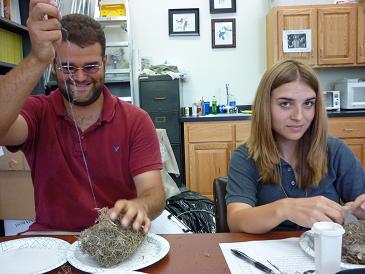

Does variation in nesting material affect egg heat retention during female incubation recess?

Although bird nest shape is highly constraint by phylogeny, the type and amount of nest material is an individual base decision. The main function of bird nest is to retain heat when the incubating bird is on the nest and during incubation recess. If the nest main function is heat regulation, the individual that participate on the nest construction should select the best type and appropriate amount of material. Although both Northern mocking genders participate on nest construction, the male is mainly in charge of the support material (mainly sticks) and female is the one that built the nest cup (fine grass fibers). The nest inner cup regulates egg temperature. We found that the amount of inner nest material provide by the female decrease as the breeding season progress. For this reason we conducted a lab experiments with three nest masses to evaluate the influence of nest mass material on egg heat retention time.

Is ambient temperature a good predictor for change on avian incubation behavior?

Many studies have showed that bird incubation behavior is affected by change in ambient temperature. Although, these studies demonstrated that ambient temperature affect avian incubation behavior, they only explain a small proportion of the variation on incubation behavior. These studies did not take in to account the ability of birds to locate their nest on different place; the temperature around the nest may not reflect the ambient. For this reason we evaluate explore if incubating female Mockingbirds are changing their incubation behavior base on the temperature around the nest or the ambient temperature.

Why birds eat fecal sacs (Monique Hiersoux)

Although coprophagy is widely spread among vertebrate, it is not well known why and when animals eat feces. We are using the Northern Mockingbird to have a better understanding of why and when birds eat their nestling fecal sacs. Moreover, we are exploring the possible mechanism that adult birds may use to know when they should eat or remove their nestling feces. We are experimentally testing one of the hypotheses (nutritional), which suggest that incubating birds eat fecal to restore energy loss during incubation. It is known that fecal sac nutritional quality decrease with nestling age. However it is unlikely that birds are able to asses this by just looking at the fecal sacs, so the must be using other indication to know when to eat or remove their nestling feces. Download poster [PDF]

Although coprophagy is widely spread among vertebrate, it is not well known why and when animals eat feces. We are using the Northern Mockingbird to have a better understanding of why and when birds eat their nestling fecal sacs. Moreover, we are exploring the possible mechanism that adult birds may use to know when they should eat or remove their nestling feces. We are experimentally testing one of the hypotheses (nutritional), which suggest that incubating birds eat fecal to restore energy loss during incubation. It is known that fecal sac nutritional quality decrease with nestling age. However it is unlikely that birds are able to asses this by just looking at the fecal sacs, so the must be using other indication to know when to eat or remove their nestling feces. Download poster [PDF]

Effects of brood size on nestling growth (Judit Ungvari-Martin)

The Northern Mockingbird have clutch that varied between two and five eggs (three been the most common one). However during the nestling phase the Northern Mockingbird experience brood reduction, creating a large brood size variation among nesting pairs. These create two different types of survival and energetic costs one is on the feeding adults and on the other one on the nestlings. From the adult perspective they should increase their feeding effort with brood size enlargement, which increase current reproductive effort and in the long term may reduce survival. Similarly, competition for food among nestling should increase with brood size; therefore adults should increase food rate delivery. Our study is study the nestling survival; growth and immune system trade-off when brood size increase. Download poster [PDF]

The Northern Mockingbird have clutch that varied between two and five eggs (three been the most common one). However during the nestling phase the Northern Mockingbird experience brood reduction, creating a large brood size variation among nesting pairs. These create two different types of survival and energetic costs one is on the feeding adults and on the other one on the nestlings. From the adult perspective they should increase their feeding effort with brood size enlargement, which increase current reproductive effort and in the long term may reduce survival. Similarly, competition for food among nestling should increase with brood size; therefore adults should increase food rate delivery. Our study is study the nestling survival; growth and immune system trade-off when brood size increase. Download poster [PDF]

Natural history of the Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos): How much do we know about females? (Molly Phillips)

Although many studies have been conducting on the Northern Mockingbird, most of this studies investigate male behavior and ecology (i. e., territoriality, mating system, survival), but specially singing behavior. Thus, female behavior and ecology have been overlooking. For this reason we are documenting female behavior and natural history especially during the breeding season, we are specifically looking at nest placement, clutch size, diet, territoriality, and length of incubation and nestling period.

Although many studies have been conducting on the Northern Mockingbird, most of this studies investigate male behavior and ecology (i. e., territoriality, mating system, survival), but specially singing behavior. Thus, female behavior and ecology have been overlooking. For this reason we are documenting female behavior and natural history especially during the breeding season, we are specifically looking at nest placement, clutch size, diet, territoriality, and length of incubation and nestling period.