¡Hola! It’s Adam, and I’m excited to share a bit of what I’ve learned with my first post.

It’s been nearly a month since I stepped into the swampy air of the Panama night. Since then, I’ve gotten used to the heat, but I also realized that the humidity now is nothing compared to what will come. We’re now between the dry and the wet seasons, and each day in the field brings a hotter sun than the last.

These are the good days, as far as hunting fossils is concerned. Dry weather keeps the rock brittle and easy to pick, but as soon as moisture creeps into the sediment, you end up trying to squeeze bones out of a goopy mess. Especially when the matrix (the rock that encases the fossils) is full of clay.

Today, I thought I’d write a bit about what we’ve been up to. I’ve tried to spell things out, in case some of this blog’s followers aren’t well versed in geology or evolutionary biology.

The rocks we work are all between 21 and 19 million years old, from a geologic period called the Miocene, however, these rocks represent a diversity of species and environments that existed in Panama at that time.

But fossils can be tricky – like when you find whole tree trunks a few meters away from tiny crab fossils! Are you on land or at sea?

We encountered this situation at a locality of the Culebra Formation just the other day. So, how do you solve this puzzle?

Based on the many characteristics of the rock unit, we can gain an understanding of what environment we’re seeing when we search through these rocks. The field of sedimentology asks questions like, “What minerals are present? Is it made of cobbles, sand, or mud? Are these pieces jagged or smooth? How is the sediment layered?” These observations narrow down the possible scenarios that led to what we see today.

In the area we visited, research has shown that these rocks formed off the coast, close enough for plants to wash in from the land. They were probably carried by rivers that emptied into shallow seas.

In the area we visited, research has shown that these rocks formed off the coast, close enough for plants to wash in from the land. They were probably carried by rivers that emptied into shallow seas.

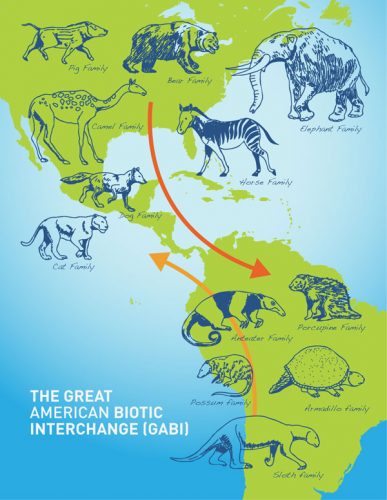

Understanding this area’s geology and stratigraphy (the patterns of layering, both at small and large scales) is crucial to interpreting Panama’s past and the biological diversity of the Americas as a whole. The isthmus is the only land connection between these two continents, and scientists have shown that this region has played a very important role in the broader development of ecosystems in both North and South America.

It’s exciting to be part of such a fascinating project! Hope you enjoyed this info. Stay tuned for more!

P.S. If you want to get to know the new field interns, check out the most recent PCP-PIRE eNewsletter.

que genial adam por tu descubrimiento de cangrejo… a mi me gustan mucho fosiles ..

saludos desde el salvador