In a previous post Sonia explained the paleohistory of the isthmus, from its volcanic beginnings to recent sedimentation. This history has been pieced together by geologists interpreting the rocks wherever they poke out of the thick tropical vegetation. We look at how the rock layers are stacked, at the size of the crystals or sediment grains that compose them, at the color the rock turns where it is exposed to air and water. A limestone suggests a shallow marine setting, while a basalt is evidence of volcanism.

Geologic history is important to the paleontologist too because fossils are nearly useless to science unless their place in time and space is understood. For this reason we headed back to Empire locality Thursday, March 12, and again this Thursday, not to search for any fossils but to try to interpret the rocks encasing them. Our colleagues who visited a couple weeks ago collected many plant and invertebrate samples from these layers, so any new information about the rock ages or depositional settings will be useful.

The outcrop is a stratigraphic mess. Faults are so pervasive that it feels like we’re standing on the shards of a shattered mirror. A folded weathered siltstone swirls delicately, bewildering our sense of verticality. Gray conglomerate lenses appear for a meter or two then pinch out again, while a pretty pink quartz arenite fault block ends as abruptly as it starts. Where to begin?

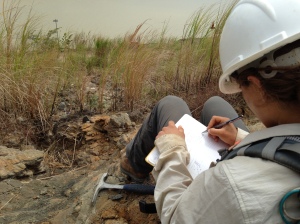

Last week we clambored all over the exposed rock, exploring. Today we picked a spot and made a rough stratigraphic column, describing the sequence from bottom to top.

We measured the dip–the angle at which these sedimentary layers are tilted–then used a Jacob’s staff to determine the actual thickness of the beds as we walked in a straight line up the section. I had never used a Jacob’s staff before but the others gave a great lesson and it turned out to be a lot of fun! We described the rock as best we could, arguing over the coarseness of a sandstone or whether the bedding could be called ‘lenticular’, and came up with some hypotheses. There are some tuff (volcanic ash) units, which we think might correspond with the upper Las Cascadas Formation, topographically above some calcareous sandstone containing oysters and other shells that reminds us strongly of other Culebra Formation outcrops. Because Las Cascadas is stratigraphically below Culebra, this would mean that the section is overturned, at least along the line we were walking. We remain puzzled by a hard, blue rock that cuts across the tuff, and we’re working on getting ahold of a higher resolution GPS so we can start to map the area. We’ll definitely be going back to try to pull a straight story from a very tangled rock.

More soon! Go Gators!