This week we had an exciting time in the field, specifically at our site under Puente Centenario. Under the shadow of the bridge and nestled among tall stands of elephant grass lies a locality deposited there some 14 to 17 million years ago. These fluvial deposits contain the remains of Panama’s Miocene animals and plants: The ancient river or stream carried teeth, bones, leaves, and other remnants, then gently buried them in sediment. After millions of years entrapped in the rock, these fossils are exhumed by our field team.

Our first excursion to this site yielded several teeth from crocodiles, fish, and even one carnivore molar.

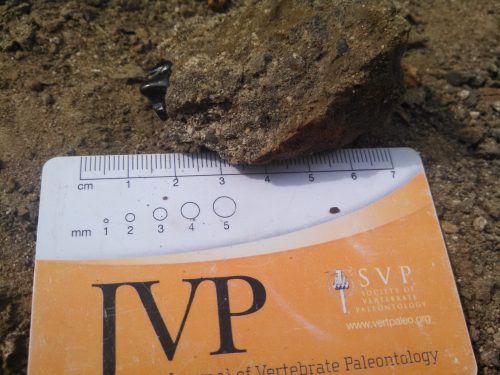

Teeth are common finds in the field because they are composed of durable enamel that preserves well over time. The enamel also lends a sheen to the fossil which makes it easy to pick out among the dark pebbles and sediment. The color of the fossil tooth is not white, as it was when the animal was alive. When the tooth gets buried, minerals in the surrounding water infiltrate the porous bone and replace the original material, resulting in a darker color.

As our field day was ending, I brushed around the area where I collected the carnassial molar and found something surprising.

We returned the next day to carefully excavate this bone. Not knowing how large this bone was, we systematically removed all the rock above and around it until we approached the bone. To strengthen and stabilize it, Jorge covered the exposed bone in paraloid, a type of thin glue that absorbs into the fossil. Using chisels and brushes, we finally freed the bone from the rock and discovered it to be a large astragalus, or ankle bone.

We are excited to send these finds to the University of Florida for further study, and to head back to the field to find more fossils!

-Dipa Desai