Andrea De Renzis and Justy Alicea | PCP PIRE Museum Interns

Recently, we traveled to Duke University to learn how the micro-CT scanner at the Shared Materials Instrumentation Facility (SMIF) works and to scan fossils collected from the Panama Canal. The main focus of our trip was to scan a set of 71 tiny rodent teeth. Traditional specimen-based research in paleontology sometimes requires destructive sampling in order to obtain measurements of features to identify specimens or understand ancient environments. Micro-CT scanning uses x-rays to create high-resolution virtual slices that, when layered together, form a three dimensional model that can be manipulated and measured. These digital models can also be shared with other researchers, educators and the public, giving more people access to fragile, rare or scientifically valuable fossils.

Before we left for Duke, we spent time preparing the specimens. They had to be removed from the pins on which they were mounted in the museum collections, and then packed into gelatin capsules. Once we had the rodent teeth ready to go, we also selected other important specimens to scan including some fossil fruits and fossil crabs. These were pilot studies to see how well the scanner could handle the fossils of tissues other than bone or enamel.

When we arrived at the SMIF lab, we met the resident technician, Jimmy Thostenson. He showed us how to set up the specimens inside the scanner. We were able to scan multiple gel caps at a time by stacking them in a tube, using foam to separate each one. Once the specimens were mounted Jimmy switched on the x-rays and we could view the live image on the computer. The SMIF lab has in-depth instructions on setting up the scanner available for free on their website. The scanner both turns the specimen and lowers it in increments as fine as 5 microns, or about 1/3 the width of a human hair. Later, as these scan slices are layered over one another, the internal and external anatomy of the object can be reconstructed in 3 dimensions. Although much of the scanning process is automated, there are some scans that still need to be manually adjusted afterwards. This happens sometimes when the scanner misaligns the center of rotation as the specimen turns during the scan.

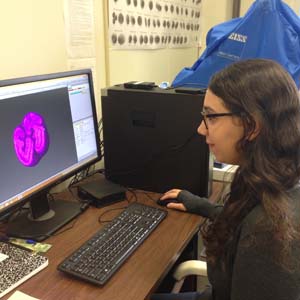

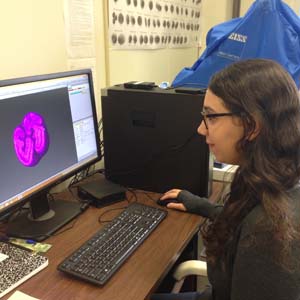

After we finished the scanning with Jimmy’s help, we began the post-processing to build the 3D model out of the files generated by the scanner. We already had some practice with this. Before our trip to Duke, we processed the data for horse teeth, shark teeth, and the bones of both an anaconda and Titanaboa. Using Avizo, we compiled the x-ray slices and then selected the specimen to separate it from the surrounding packing material. This is a challenging part of the process because it is important to select the right amount of threshold to accurately capture the surface. The computer/program does not know the boundaries of what you are selecting, so if a specimen of the same density is touching the one you are trying to select, it will show in the scan as the same gradient and select both. Teasing these elements apart can be frustrating and painstakingly time consuming. Thoughtful planning beforehand of the scanning being done is the best way to avoid kicking yourself later.

The shark, horse and snake bones have been archived online at MorphoSource and have already been used as parts of lessons in k-12 classrooms through GABI-RET. Our 3D images have even been 3D printed for use in classrooms as well. Seeing how our processing work has been put to use has made it all the more rewarding and we hope to continue using micro-CT scans to not only help scientists collect valuable data, but also to help teachers incorporate paleontology/earth science into their classrooms.

We are still processing all the data from the rodent teeth, as well as the crabs and fruits. Once these are done they will be used in ongoing research projects and eventually used in lesson plans. It may sound like a highly technical process, but the procedure is straightforward once you know what you are looking for. Great resources for further information on specific steps can be found at UT Austin and Duke University‘s digital imaging websites.

Justy Alicea and Andrea De Renzis are Museum Interns with PCP PIRE. They also regularly post about their research on the blog [Andrea; Justy]. For a more in-depth description of the scanning preparation and process, see the unabridged article there.

Andrea De Renzis and Justy Alicea | Practicantes del PCP PIRE

Recientemente viajamos a la Universidad de Duke para aprender cómo funciona el escáner micro-CT en el Centro de Materiales e Instrumentación (SMIF) y para escanear fósiles colectados en el Canal de Panamá. El objetivo principal de nuestro viaje fue el escanear un conjunto de 71 dientes de pequeños roedores. La investigación tradicional en paleontología a veces requiere un muestreo destructivo con el fin de obtener mediciones de características que permitan identificar especímenes o entender los ambientes antiguos. El escaneo de micro-CT utiliza rayos X para crear rebanadas virtuales de alta resolución y al juntar las capas se forma un modelo tridimensional que puede ser manipulado y medido. Estos modelos digitales también pueden ser compartidos con otros investigadores, educadores y el público, permitiendo a más personas acceder a fósiles frágiles, raros o científicamente valiosos.

Antes de que partiéramos hacia Duke, pasamos un tiempo preparando las muestras. Se tuvieron que retirar los pines en los que fueron montados en las colecciones de los museos, y luego empaquetados en cápsulas de gelatina. Una vez que tuvimos los dientes de roedores listos, seleccionamos otros especímenes importantes para escanear los cuales incluyeron algunas frutas y cangrejos fósiles. Estos representaron estudios piloto para ver qué tan bien el escáner podría manejar los fósiles de tejidos distintos de hueso o esmalte.

Cuando llegamos al laboratorio SMIF, conocimos el técnico residente, Jimmy Thostenson. Él nos mostró cómo configurar las muestras dentro del escáner. Fuimos capaces de escanear varias cápsulas de gel a la vez apilándolas dentro de un tubo, utilizando espuma para separar cada muestra. Una vez las muestras montadas, Jimmy encendió las radiografías y pudimos ver la imagen en directo desde la computadora. El laboratorio SMIF tiene instrucciones detalladas sobre cómo configurar el escáner disponible de forma gratuita en su página web. El escáner convierte al espécimen y lo reduce en secciones tan finas como 5 micrones, o alrededor de un tercio de la anchura de un cabello humano. Luego, ya que estas rebanadas están ordenadas en capas una sobre otra, la anatomía interna y externa del objeto puede ser reconstruida en 3 dimensiones. Aunque gran parte del proceso de escaneado está automatizado, hay algunos escaneos que deben después ser ajustados manualmente. Esto ocurre a veces cuando el escáner desalinea el centro de rotación mientras la muestra gira durante el escaneo.

Después de haber terminado el escaneo con la ayuda de Jimmy, empezamos el proceso posterior para construir el modelo 3D a partir de los archivos generados por el escáner. Ya teníamos un poco de práctica con esto. Antes de nuestro viaje a Duke, procesamos datos correspondientes a dientes de caballo, dientes de tiburón y huesos de tanto una anaconda como de una Titanaboa. Usando Avizo, compilamos las capas de rayos X y luego seleccionamos la muestra para separarla del material de embalaje de los alrededores. Esta es una parte difícil del proceso, ya que es importante seleccionar la cantidad correcta de umbral para capturar con precisión la superficie. El equipo/programa no conoce los límites de lo que uno está seleccionando, por lo que si un objeto de la misma densidad está tocando lo que uno está tratando de seleccionar, se mostrará en el escaneo como el mismo gradiente y se seleccionará ambos. Separar estos elementos puede ser frustrante y consumir mucho tiempo. La cuidadosa planificación de la digitalización es la mejor manera de evitar cometer errores más tarde.

Los huesos de tiburón, caballos y serpientes han sido archivados en línea en MorphoSource y ya se han utilizado como parte de lecciones para clases de inicial y primaria a través del proyecto GABI-RET. Nuestras imágenes 3D, incluso se han impreso en 3D también para su uso en las aulas. El ver cómo nuestro trabajo de procesamiento ha sido tan bien usado ha hecho que el trabajo sea más gratificante por lo que esperamos seguir realizando escaneos micro-CT, no sólo para ayudar a los científicos a recopilar datos valiosos, sino también para ayudar a los maestros a incorporar la paleontología/ciencias de la tierra en sus aulas.

Todavía estamos procesando todos los datos de los dientes de roedores, así como de los cangrejos y de las frutas. Una vez que estos se finalicen serán utilizados en proyectos de investigación y posteriormente en lecciones escolares. Puede sonar como un proceso muy técnico, pero el procedimiento es sencillo una vez que se sabe lo que se está buscando. Muy buenos recursos para obtener más información sobre los pasos específicos se pueden encontrar en sitios web de imágenes digitales de las Universidades de Austin en Texas y en la Universidad de Duke.

Justy Alicea y Andrea De Renzis son practicantes del PCP PIRE. Ellos publican regularmente sobre sus investigaciones en el siguiente blog [Andrea; Justy]. Para una descripción más detallada sobre el proceso de preparación y escaneado, consulte el artículo íntegro allí.