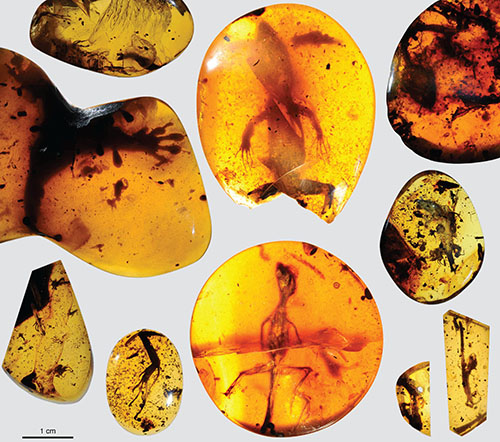

Photo courtesy of David Grimaldi

Editor’s note: New fossil discoveries show this specimen is an amphibian known as an albanerpetontid, not a chameleon. Even though one is an amphibian and the other a reptile, albanerpetontids and chameleons share some features, including large eye sockets, scales, claws and — we now know — a rapid-fire tongue.

About 100 million years ago an infant lizard’s life was cut short when it crawled into a sticky situation.

The early chameleon was creeping through the ancient tropics of present-day Myanmar in Southeast Asia when it succumbed to the resin of a coniferous tree. Over time, the resin fossilized into amber, leaving the lizard remarkably preserved. Seventy-eight million years older than the previous oldest specimen on record, the dime-size chameleon along with 11 more ancient fossil lizards were pulled—encased in amber—from a mine decades ago, but it wasn’t until recently that scientists had the opportunity to analyze them.

In “Jurassic Park,” fictional scientists cloned dinosaurs with blood extracted from amber, but these real-life fossils hold snapshots of “missing links” in the evolutionary history of lizards that will allow scientists to gain a better understanding of where they fit on the tree of life, said Edward Stanley, a postdoctoral researcher in herpetology at the Florida Museum of Natural History on the University of Florida campus.

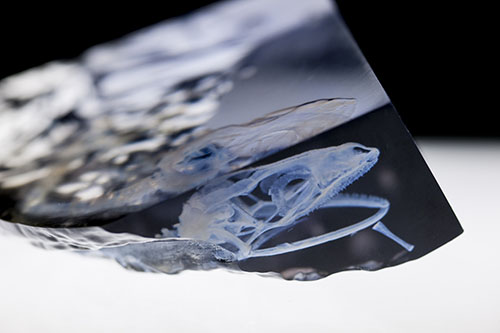

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Of the 12 lizard specimens, three—a gecko, an archaic lizard and the chameleon—were particularly well-preserved. The new species will be named and described in a future study.

“These fossils tell us a lot about the extraordinary, but previously unknown diversity of lizards in ancient tropical forests,” said Stanley, co-author of a new study that first appeared online March 4, 2016, in the journal Science Advances. “The fossil record is sparse because the delicate skin and fragile bones of small lizards do not usually preserve, especially in the tropics, which makes the new amber fossils an incredibly rare and unique window into a critical period of diversification.”

Stanley first encountered the amber fossils at the American Museum of Natural History after a private collector donated them. He knew the fossils were ancient, but it was a combination of luck and micro-CT technology that allowed him to identify the oldest chameleon.

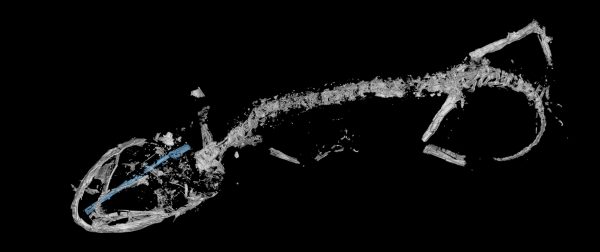

Florida Museum scan by Edward Stanley

“It was mind-blowing,” he said, to see the fossils for the first time. “Usually we have a foot or other small part preserved in amber, but these are whole specimens—claws, toepads, teeth, even perfectly intact colored scales. I was familiar with CT technology, so I realized this was an opportunity to look more closely and put the lizards into evolutionary perspective.”

A micro-CT scanner made it possible for study researchers to look inside the amber without damaging the fossils and digitally piece together tiny bones and view internal soft tissue. Scanned images of the detailed preservation provided insight into the anatomy and ecology of ancient lizards, Stanley said.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

The amber gecko, for example, confirms the group already had highly advanced adhesive toe pads used for climbing, suggesting this adaptation originated earlier. As for the Southeast Asia chameleon, the find significantly pushes back the origins of the group and challenges long-held views that chameleons got their start in Africa. Stanley said it also reveals the evolutionary order of chameleons’ strange and highly derived features. The amber-trapped lizard has the iconic projectile tongue of modern chameleons, but had not yet developed the unique body shape and fused toes specially adapted for gripping that we see today.

Stanley said the fact that these incredibly ancient lizards have modern counterparts living today in the Old World tropics speaks to the stability of tropical forests.

“These exquisitely preserved examples of past diversity show us why we should be protecting these areas where their modern relatives live today,” Stanley said. “The tropics often act as a stable refuge where biodiversity tends to accumulate, while other places are more variable in terms of climate and species. However, the tropics are not impervious to human efforts to destroy them.”

Learn more about the Herpetology Collection at the Florida Museum.