If you have ever collected shells on a beach in Southwest Florida, you almost surely have a lightning whelk in your possession. This beautiful mollusk (Sinistrofulgur sinistrum) is named for the colorful, jagged lines visible on its outer surface.

It lives in marine waters of the southern Atlantic coast of the U.S., much more frequently along the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Keys to Texas, and along the Mexican Gulf coast as far as the Yucatán peninsula. The whelk grows slowly and can live for many years, with some individuals growing to over a foot long. One of the biggest lightning-whelk shells in the world can be seen on Sanibel Island at the Bailey-Matthews National Shell Museum.

There are many fascinating shells, so what’s so special about a lightning whelk? If you have a collection of seashells, get it out and find all the snails—the ones that spiral, as opposed to the bivalves, such as clams and oysters, which have two flat sides. Now lay out all the snails with their spires up (the spire is the swirly end, where the helix gets smaller and smaller until it comes to a point.) If you have a lightning whelk in your collection, you’ll quickly see that it is distinctive in one obvious way: it opens on the left, not the right. Such snails are referred to as sinistral; those that open on the right are called dextral. Another way of expressing this is to say that when viewed from the top of the spire, and then tracing the helix from the edge into the center, the lightning whelk shell spirals clockwise, not counter-clockwise as do almost all other snails in the world.

Tens of thousands of lightning whelk shells are found along with other debris in southwest Florida middens, their fleshy parts having been eaten by people, in many cases several hundred years ago. The whelks were gathered from nearby shallow-water estuaries. Although fish contributed the great majority of the protein intake for the Calusa, shellfish were always important. Sometimes the Calusa used whelk shells for making tools. They selected only the larger and thicker individuals for this purpose.

But in places far from coasts, where lightning whelks do not live naturally, the whelk shells had special ritual significance. Artifacts made from them were included with human burials between 6,000 and 3,000 years ago, especially in western Kentucky, northern Alabama, and western Tennessee. Beads, drinking vessels, pendants, gorgets (decorative items worn at the neck), and other items were made from lightning whelk shells, which came from the Gulf of Mexico, some 500 miles away.

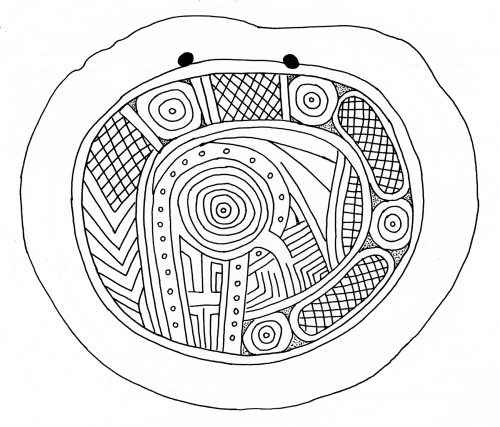

Perhaps the best known lightning-whelk artifacts are gorgets and drinking vessels made in the Southeast between 500 and 1,000 years ago. Most gorgets are circular, with two suspension holes near the edge. Some gorgets show a rattlesnake in a coil with its head near the center. The head of the snake is sometimes indicated as a series of concentric circles, with smaller sets of concentric circles elsewhere on the body and a distinctive rattle at the tail. More than 90% of all known rattlesnake gorgets show the snake moving in a sinistral spiral.

The two of us recently published a paper in which we show evidence that the spiral is a metaphor for the continuity and inevitability of time, with references to cycles of birth, death, and rebirth, and the triumph of sun/fire over darkness/death. You can read this paper in the RRC library in the Ruby Gill House, or find the article on line or in a university library (see reference below).

Historical accounts of more recent Indian people in the southeastern U.S. show that sinistral (clockwise) spirals are associated with the sun and its movement. Fire represented sun on the earth. For example, among the Creek Indian people in the late 1700s, William Bartram observed a council meeting in which a fire had been laid in a sinistral spiral around the central pillar of the council structure. Lit from the exterior end, it burned slowly but steadily “with the course of the sun,” until the fuel was consumed. For Creek people, the sinistral spiral represented the daily path of the sun and traced the direction of life, from birth toward death, imitating how the sun is born in the east and dies in the west each day. A similar council fire spiraling around a central post was a feature of the Cherokee council house.

Spirals also take on ritual significance in community dances. The most frequent dance direction among the tribes east of the Mississippi River was counter-clockwise. Certain dances were performed only by men, others only by women. Most southeastern dances were named after animals. Some animals named in dances were associated with the path toward death, as were warriors. Others were associated with the path toward life, as were women. Some animals received special attention because they were important foods. Two animals in particular—snakes and owls—were associated with illness or death.

Legends indicate that snakes are capable of dealing death, often tricking or trying to kill people. Southeastern peoples avoided killing snakes in order to avoid retribution from other snakes. Rattlesnakes typically coil in a spiral with the head in the center. This further associates snakes with the spiral, death, and war, as in the Cherokee Warrior’s Mask, which has an image of a coiled rattlesnake on top of the warrior’s head.

Image courtesy McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture

Snake and Owl dances are both clockwise and counter-clockwise. The most detailed description of the Snake Dance is from the Cherokee, but it also occurs among the Choctaw, Alabama, and Chickasaw. Participants first dance counter-clockwise toward the center, forming a spiral. At the center, they reverse direction and file outward in a clockwise direction. Then they move to another part of the dance ground and dance into another spiral, this time clockwise toward the center, and again reverse their steps in a counter-clockwise spiral. The Horned Owl dance among the Creek was performed in a similar manner, and was always in September. In the longer paper, we bring several lines of evidence to bear on these interpretations, demonstrating, we believe, the significance of the sinistral spiral in Native American symbolism, and the role of the lightning whelk in representing that spiral.

Lightning whelk artifacts are found in archaeological sites from Florida to Manitoba, Canada, and from Oklahoma to New York State, and almost all of them came from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico. Beautiful though they are when fresh, and useful though they were to the Calusa for food and tools, we think it is neither color, nor size, nor ease of acquisition that motivated Indian people to seek out lightning whelks for artifacts. It is the specific left-handed (sinistral, clockwise) coiling direction that makes this whelk so valuable and sacred outside of Gulf coastal Florida. In short, the sinistral spiral was an icon of eastern Native American spirituality, and the lightning whelk served as a physical reminder of this very important principle.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 15, No. 3. September 2016.