In May and June of 2013 and 2014, with funds from the National Geographic Society and the University of Georgia’s Office of Sponsored Programs, as well as logistical assistance from the Randell Research Center/Florida Museum of Natural History and the collaboration of Karen Walker, Amanda Roberts Thompson, Lee Newsom, Elizabeth Reitz, and Michael Savarese, we conducted research at Mound Key, an island in Estero Bay near Fort Myers Beach.

The 2014 field season was enhanced by the assistance of archaeological field school students from Florida Gulf Coast University (FGCU), under the direction of Alison Elgart and Mike McDonald.

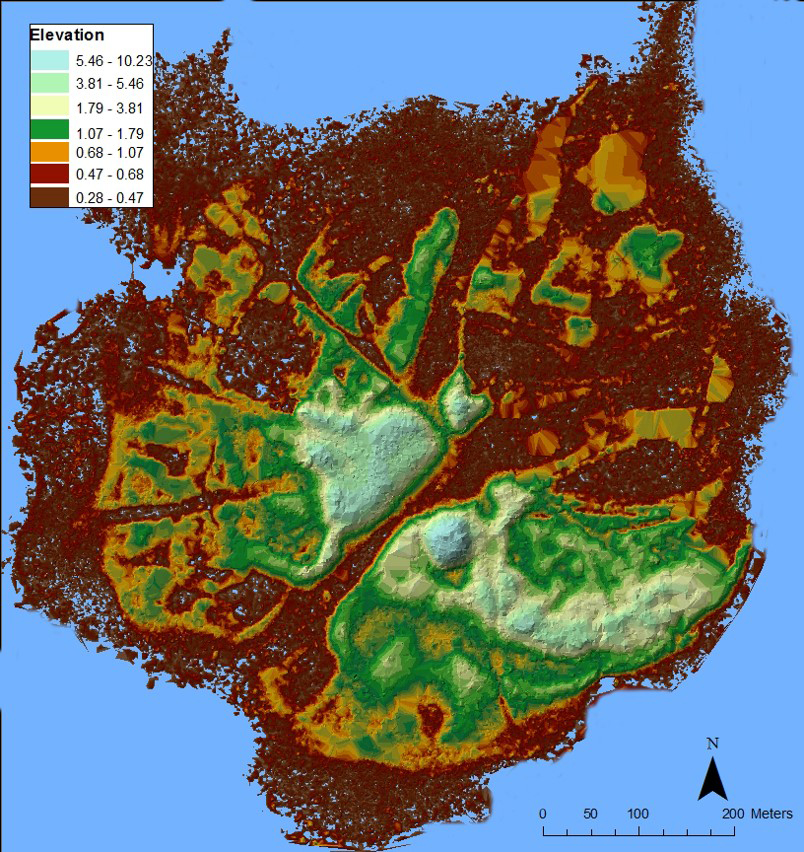

When the Spaniards first sailed into Southwest Florida waters in the 1500s, Mound Key was the capital of a vast Calusa domain that stretched throughout South Florida. Then known as Calos, the site is today a complex of mounded middens (ancient refuse deposits), one of which rises over nine meters high and is adjacent to a canal that bisects the island. Much of what we know about this Calusa town comes from documents, including the account of Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, who spent 17 years among the Calusa before being returned to Spain by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. In 1566, Menéndez established Fort San Antonio at Calos and within a year the first Jesuit missionaries in North America arrived there. A later attempt to convert the Calusa took place in the late 1600s, this time by Franciscans, but both missions were failures. Documents concerning the Spaniards’ time on Mound Key describe both the fort and the Calusa king’s house, which was said to be large enough to hold 2,000 people. We reasoned that the two largest mounds at the site are the likely locations for these structures, so we applied both new and old technologies to find and investigate them.

Remote Sensing

To help plan the excavations, we created a detailed topographic map of the site using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data available through the state of Florida. Then we conducted a shallow geophysical survey on both of the large mounds—the possible locations of the fort and the king’s house. The best results were from the ground penetrating radar (GPR).

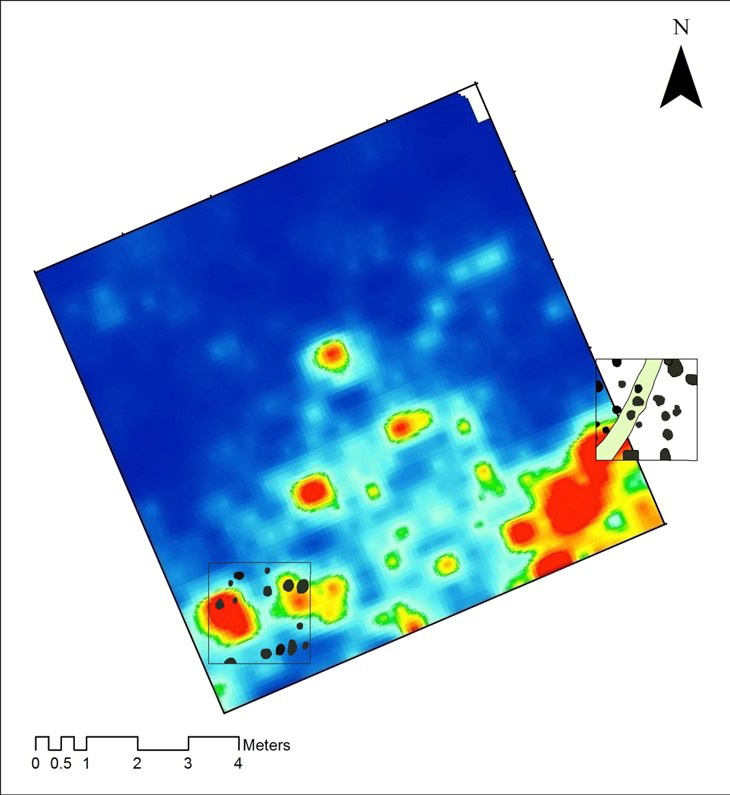

We reasoned that if the king’s house was located on Mound 1 and was even close to the size reported by the Spaniards, then it likely encompassed the entire summit. Therefore the walls of such a structure would be located near the edge of the mound summit. Indeed, the GPR results indicated a curvilinear pattern along the edge of the mound.

On Mound 2, we ran GPR over a 20-x-20-meter area where we predicted the fort would be located, based on Spanish descriptions, previously recorded Spanish artifacts in the area, and prior research done by Bill Marquardt, Corbett Torrence, and Sam Chapman in 1994. Here the GPR results showed linear patterns that appeared to represent a structure or walls.

Excavations

Based on the GPR results, we excavated in the vicinity of the patterns we had detected on both Mounds 1 and 2. We excavated using hand tools in 10-cm (4-inch) arbitrary levels, with careful attention to changes in soil color and compaction. All materials were sieved through 1/8-inch-mesh screens.

In both units evidence of structural remains is abundant. On Mound 1, the excavation revealed that instead of a wall, the signals were detecting what could be termed a “builder’s trench.” On either side of this “trench” there is a line of post molds. While the post molds vary in size, many are large (about 25 cm, or 10 inches, in diameter), suggesting substantial support posts of a large structure.

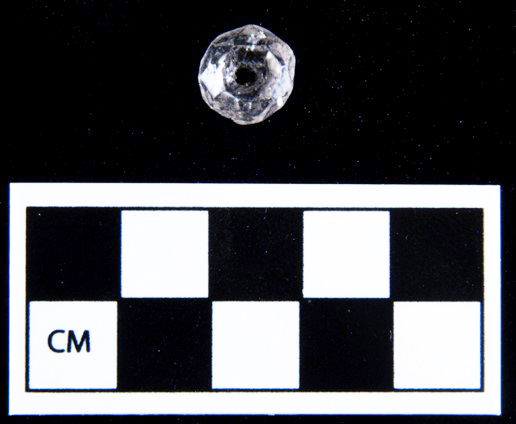

The excavation on Mound 2 was placed in the vicinity of the rectangular pattern of high-amplitude reflections revealed by GPR. Similar to Mound 1, there were numerous posts identified in the excavation, but these contained many more Spanish-period artifacts, including majolica sherds, olive jar fragments, and other historic artifacts. Radiocarbon dates on two of the posts suggest that some of these may be related to structural remains associated with San Antonio de Carlos.

Radiocarbon Dates

To date a total of seven radiocarbon dates have been run on Mound Key materials. The earliest dates on these materials come from the general midden deposits in both of these units, but the posts are much younger than the surrounding midden, in some cases by several hundred years. There are two possible explanations. First, areas of Mound Key may have been abandoned or unoccupied for some time before posts were placed into the older midden. Second, and more likely, the Calusa were mining and recycling older midden as part of their construction technique to build houses. Currently, we are in the process of running an additional 30 radiocarbon dates from the various excavations at the site. These new dates will aid in our understanding of how long the site was occupied and how quickly the various shell accumulated over time.

Zooarchaeology

Under the supervision of Elizabeth Reitz, Shelby Jarrett conducted limited analysis of a sample of the animal bones at the University of Georgia Zooarchaeological Laboratory. Although we recovered animal bones from both Mounds 1 and 2, our analysis focused on samples from Mound 2. Unfortunately, because we believe that much of what we excavated represents repurposed midden (see above), we cannot be sure to what degree these samples are the remains of food eaten by Calusa people at these specific areas of the site. That is, these remains may be brought in for construction from other areas of the site. Again, we are working on testing this hypothesis. Nonetheless, at least some of the uppermost levels in the unit may represent animal remains associated with the Spanish fort occupation. At least one bone identified as representing sheep/goat shows butchering marks from a metal tool. Neither sheep nor goats nor metal tools would have been available to the Calusa before Spanish contact.

Oyster Shell Analysis

Mike Savarese and his Conservation Paleobiology students at FGCU did a pilot study of oyster (Crassostrea virginica) shells from Mound Key. In collaboration with Karen Walker, samples from several time periods were selected for study. For comparison, a much earlier sample from Useppa Island and a modern one from Estero Bay were included. The oysters were sorted into categories based on the amount of biocorrosion and encrustation within the interior surfaces of the oyster shells. Length and widths of the shells were also measured.

They found that each of the archaeological samples was near pristine (that is, no biocorrosion/encrustation) whereas the modern sample was significantly more fouled. In other words, the archaeological sample represents oysters that were collected alive (unopened shells would not have accumulated barnacles and other animals on their interiors). This means that the archaeological oysters were initially collected for consumption rather than merely for mound-building material.

The measurements show that the older oysters from Useppa were the largest, and that the oysters at MoundKey became smaller through time. This shows that the Calusa people had an impact on the local oyster population. The largest oysters are the modern ones from Estero Bay, much larger than the ones from Mound Key, and also even larger than the much older Useppa ones. This is not surprising because no commercial harvesting has occurred in Estero bay since the mid-1950s.

Paleoethnobotany

A sample of the carbonized botanical remains was sent to Lee Newsom of the Department of Anthropology at Pennsylvania State University for analysis. Pine was the most common species identified and most likely represents the type of tree chosen for posts. Other types of wood were likely brought to the site along with the post material. It also appears that pine was cut down away from the site and brought in to construct the posts.

Conclusion

We believe we have good evidence of two or more structures at Mound Key that are related to the pre- and post European-contact occupations. There is tentative evidence that we have identified either the king’s house described in the sixteenth-century documents or perhaps an earlier version of that structure. Further excavation will be needed to confirm either interpretation. In addition, we also have evidence of possible structures associated with the fort on Mound 2. Although the posthole patterns in these excavations are less clear, the associations between these posts, Spanish period artifacts, and radiocarbon dates place these features within the sixteenth-century occupation of the site and possibly the fort itself. In addition to locating these structures, our excavations indicate possible construction techniques that involved the recycling of midden in the construction of large buildings. More dates will be needed to confirm these interpretations.

Mound Key is a significant site, but has not received the attention it deserves from archaeologists. Up to this point, the identification of Mound Key as the capital has been based on historical documents. Our research has, for the first time, provided some architectural evidence to bolster the claims that this site was indeed the capital of the Calusa at European contact. Further, our work is shedding light on Calusa house constructions. This is a topic about which we know very little, but is an emerging area of study (see RRC Friends Newsletter for June, 2014). Further research will add to our knowledge of the nature of Calusa life and their interactions with Europeans during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 14, No. 1. March 2015.