Most of us set a little money aside in case of unexpected needs. In Florida, during hurricane season, some of us stash some extra water and food, just in case there’s no electricity for a spell. In a way, this is storage of surplus – setting aside some resources in case of need.

But now think of surplus at a broader scale. Suppose you are a farmer who has a bumper crop in corn or beans this year. You could sell it at a cheap price, or just let it rot, or you could share it with friends or kinfolk elsewhere whose crops didn’t do as well as yours. Next year, if their fields are productive and yours aren’t, they will return the favor. By cooperating, everybody is better off in the long run. This is called reciprocity, and it is a step above the “rainy-day fund” kind of surplus with which most of us are familiar. Now imagine an even more complex kind of surplus exchange. In this situation, surpluses are brought to a central place, where they are redistributed by a leader, who gains status and power by virtue of this position.

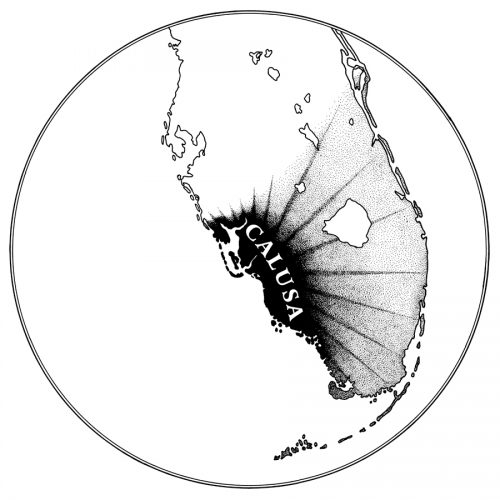

In fact, surplus production is often linked to social development and the rise of politically complex societies. Largely, however, anthropologists have focused on agricultural societies, and few scholars have considered how surpluses were produced and managed by non-farming societies. We all know that the Calusa Indian people of Southwest Florida were politically powerful and socially complex in the 1500s, and we also know that they were fisherfolk, not farmers. How, then, were they able to support their own people and control most of south Florida without producing agricultural surpluses?

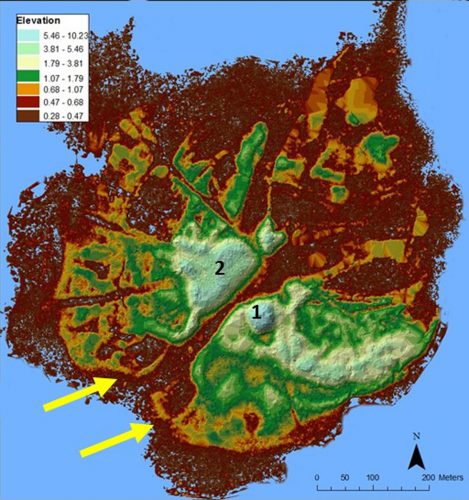

With support from the National Science Foundation, Bill Marquardt (Florida Museum of Natural History), Victor Thompson (University of Georgia), and Michael Savarese (Florida Gulf Coast University), along with Lee Newsom (Flagler College), Elizabeth Reitz (University of Georgia), Amanda Roberts Thompson (University of Georgia), and Karen Walker (Florida Museum of Natural History) will conduct research at the Mound Key and Pineland archaeological sites to investigate the role of surplus production among the Calusa, the most powerful group in peninsular Florida in the 1500s. The Calusa king collected tribute from a population in excess of 20,000 distributed among 50 to 60 Calusa communities and extending to many other towns, from the northern reaches of Charlotte Harbor to the Florida Keys. However, unlike the farming people of the interior river valleys of the southeastern U.S., the Calusa relied primarily on fi sh and shellfish for protein, collecting wild plant foods and using only a handful of plants from home gardens.

Most importantly, they did not grow maize (corn), which formed the basis of surplus production and political complexity for many groups across the Southeast. Few archaeologists have examined surplus production among fisher-gatherer-hunters, especially those in the sub-tropics. We hope to shed light on long-term sustainability of fisheries, a topic of considerable world-wide interest, and address the potential impact of over-harvesting shellfish. We also want to determine if the Calusa purposely developed ways to produce more food as their population increased and competition with Indian people in the Tampa Bay area became more significant.