These days, climate change is center-stage. Understandably most of the attention is on global warming and sea-level rise. Many wonder what a warmer future will be like in places around the world, including southwest Florida.

But what would life in coastal southwest Florida be like if the opposite happened? Pineland’s ancient residents, a fishing people, likely discovered the answer to that question.

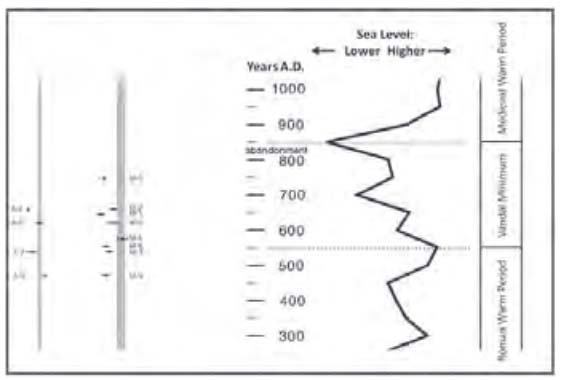

By A.D. 500, a lot of people were living at Pineland and rather profitably. But beginning about A.D. 550, a disruptive cascade of three cooling events and sea-level falls may have occurred there, ending around A.D. 850. This, a working hypothesis, is based on regional climate and sea-level records paired with Pineland’s archaeology. Much of this time span is often referred to as the “Dark Ages” in European history in part because it was a time of cold climate, drought, famine, and plague (“Vandal Minimum” is another name). People in many places in the world experienced similar hardships. A famous example is that of the Mayan people, who were impacted by a series of droughts culminating in the ninth century. Were these centuries also a “Dark Age” for Pineland’s residents?

Much of the excavated archaeological evidence says “yes.” While some of us instantly think that a little cooling off in subtropical south Florida surely was a good thing (and maybe it was initially), we must consider that the associated conditions of sea-level fall and possibly drought might have been problematic, especially for people who depended on the shallow waters of Pine Island Sound for fish and shellfish. The evidence is varied:

- a sudden and sustained availability and use of migratory ducks for food (indicating cooler temperatures);

- a shift from black-mangrove firewood to pine, and a reduction of available ribbed mussels (both suggesting a drying of wetlands);

- a shift in house locations from higher, landward areas to lower, seaward elevations (suggesting lowered water levels);

- deposition of middens on dry land at elevations that are below twentieth-century mean sea levels;

- an overall reduction in diversity of aquatic foods and low numbers of the salt-loving, non-food crested oyster (both indicating sustained lowered salinities suggestive of lowered sea level);

- a reduction in available food oysters, an increase in marine snails (especially crown conch), and a decrease in available fish (all suggesting lowered water levels);

- and perhaps most dramatically, the absence of archaeological deposits dating to A.D. 800-900 (indicating Pineland’s temporary abandonment).

While these puzzle pieces have fallen neatly into place, we wanted to test our working hypothesis with an additional, more direct line of evidence for climate change at Pineland. Because there is no existing local paleoclimate record, we decided to develop one based on the geochemistry of archaeological shells of southern quahog clams (Mercenaria campechiensis) and otoliths of marine catfish (Ariopsis felis), both plentiful at Pineland. Both shells and otoliths record chemical signatures of the water in which the clams and catfish lived. The signatures are preserved in archaeological specimens and they can be “translated” into ancient water temperatures and relative precipitation measures.

With support from the National Science Foundation, we began the project first by studying modern estuarine water conditions along with a modern population of quahog clams and a few catfish specimens (see Friends of Randell Research Center newsletters Vol. 1, No. 3 and Vol. 2, No. 3). The results of this work were used by paleoclimate scientist Donna Surge and her graduate students as a comparative baseline. Mean – while, the Florida Museum’s Austin Bell systematically organized and curated the extensive collection of Pineland clam-shell and otolith specimens, and environmental archaeologist Karen Walker researched those collections, selecting specimens to send to Surge’s laboratory at the University of North Carolina. There, graduate student Ting Wang prepared the specimens and then extracted carbonate powder from multiple shell/otolith layers using a computerized micromill. Samples of powder from the first group of specimens, those dating to the A.D. 450- 850 period, were then analyzed.

Briefly, here are the results. Specimens M-9 and A-9 (M = Mercenaria clam, A = Ariopsis catfish) come from Surf Clam Ridge and date to A.D. 450- 500; A-9 recorded the warmest temperature of all specimens, correlating well with a time just prior to the first sea-level fall. M-7, A-7, M-6, and M-4 from Old Mound indicate cool and mostly dry conditions correlating with the A.D. 500-550 fall. From Brown’s Complex (BC), M-8 and A-8 date to the A.D. 600-650 increment and indicate relatively warm and wet conditions, which supports a temporary recovery of wetlands (indicated by ribbed mussel shell and black mangrove wood counts) and correlates with a rebound in sea- level. M-2, A-2, and M-1, also from BC, date to A.D. 650-700 and indicate the coldest and driest conditions, corresponding to the second fall in sea level. M-5 is from the latest midden of this period in BC and dates to A.D. 700-750. It indicates a continuation of dry conditions.

The geochemical results support the earlier archaeological findings. A picture emerges of a people adjusting to episodic, deleterious changes in their land and estuarine environments. But with the final punctuated drop in water translating into a largely dry Pine Island Sound, Pinelanders left their home site. Ultimately, people dependent on fish and shellfish must follow their livelihood. We speculate that they moved to the far western part of Pine Island Sound. One possible relocation site is Useppa Island, where a midden dense with high- salinity molluscan shells dates to the ninth century A.D. Wang will be analyzing a clam shell and a catfish otolith from this context in the coming months. The Pinelanders later returned to their ancestral home, but it was not until about A.D. 900, when sea water once again filled Pine Island Sound, bringing with it teeming populations of fish and shellfish.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 9, No. 2. September 2010.