Numerous new arthropods show up in Florida every year with several of them becoming invasive pests that potentially threaten food crops, landscapes, and native habitats.

For a new pest to thrive and establish, it needs suitable host(s) and environmental conditions. When these conditions are met, the pest population often explodes and the chance of spreading to new areas is almost automatic.

This scenario is common and usually for the first several years pest populations can be devastating. The lack of competitors and natural enemies contribute to pest explosions. As a result the pest population increases rapidly but will also often decrease after several years as a natural balance of the pest is established for its optimal survival. A decrease in population can be associated with an increase in natural enemies and competitors as well as with other management strategies. However, it may not decrease to the point that no management is necessary.

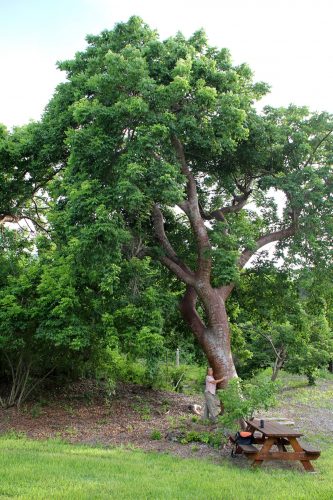

The Rugose spiraling whitefly was first identified in Miami-Dade County in 2009 (Fig. 1) and was verified at the RRC’s Calusa Heritage Trail in August 2011. It has since spread to numerous counties in south and central Florida; particularly up the coasts. This whitefly feeds on many native and non-native host plants. Those most significantly infested at the RRC were gumbo limbos and strangler figs. However, the female will lay eggs on most plants as well as walls or other structures. This whitefly can cause damage to plants, especially those experiencing other stressors such as drought or impacts from cold weather. One of the biggest issues is the excessive white wax it produces, the excessive honeydew it excretes, and the subsequent black sooty mold that grows on the honeydew.

Because the Calusa Heritage Trail offers a landscape of diverse insects and plants, a group of infested trees became part of a small study to compare pesticide treated trees to those with no treatment. The trees with no treatment were evaluated for the presence of natural enemies. And, in November 2011, a tiny predatory beetle, Nephaspis occulatus, and a parasitic wasp, Encarsia guadeloupe, were released.

There have been several natural enemies attacking the whitefly. It now appears that another parasitic wasp, Encarsia noyesi (Aphelinidae) seems to take over and have the greatest impact on the whitefly. This parasitic wasp is very tiny and will not sting people; in fact, you will likely never notice it is there. It was first collected in 2012 and appears to be following the whitefly population. In addition to its natural movement, the University of Florida has been collecting, rearing, and releasing it to new areas. Once the parasitic wasp is well established in an area, the population of whitefly drops dramatically. Currently in Monroe, Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach Counties where whitefly infestations were extremely heavy, there is very little Rugose spiraling whitefly. And, as of this writing, the same is true at the Calusa Heritage Trail. No pesticide treatments are occurring and staff are keeping a close eye on the vitality of the trees. Some trees have been trimmed by an expert service to encourage new leaf and branch growth and discourage breakage of heavy older limbs.

The good news for the home or landowner with Rugose spiraling whitefly infestation is that you can likely expect to see a decline in this whitefly. It is even more important now that each infestation be evaluated to determine if a pesticide is necessary (i.e., is there sufficient whitefly) as well as to use the most appropriate products and methods to protect natural enemies. If you have been using pesticides on a regular schedule to control this whitefly, now is the time to evaluate whether continued pesticide application is the best approach. These pests, in general, do not go away completely but with the natural enemies can be maintained at very low populations that require little or no management.

Now, here is the bad news related to the decline in Rugose spiraling whitefly and specifically gumbo limbo trees. Before the whitefly became a problem, there was another pest, croton scale (Phalacrococcus howertoni), infestingmany gumbo limbo trees. This scale insect can feed on numerous types of plants, but in the landscape is often on gumbo limbo trees and crotons. When the Rugose spiraling whitefly started infesting gumbo limbo trees, we began to see less croton scale. Now that we are seeing less whitefly, we are seeing more scale again. The croton scale is found on the stems and underside of the leaves. The adult female is oval, relatively fl at, and greenish-yellow with some dark spots or striations. The immature stages are smaller, yellowish, and also oval and fl at. Like the Rugose spiraling whitefly, the croton scale produces excessive honeydew. So the problems associated with honeydew such as the growth of sooty mold could still be happening on gumbo limbo trees due to a different insect.

In 2009, a ladybird beetle predator, Thalassa montezumae, was found feeding on the croton scale. This was the first time this predator had been reported in Florida. It was likely introduced with the croton scale. The species is known from Mexico, Arizona, and Texas and appears not to feed on many other insects other than croton scale. The adult is small (less than 6 mm), a dull, metallic blue with two yellow or red spots. The larvae of this ladybird beetle resemble mealybugs because they are covered in a white, waxy substance. Often, until the excessive honeydew becomes a problem, the croton scale goes unnoticed because it blends well into the stems and leaves. By the time a problem is noticed, there are often predatory beetles already feeding on the scale. However, the adult is very small and also not very noticeable. The beetle larvae, on the other hand, are much more noticeable but are often mistaken as a pest. Treating these beetle adults and beetle larvae with care will allow them to be part of the arsenal to protect gumbo limbo trees from the croton scale.

Many invasive pest populations do ultimately decline, and although they do not go away completely, do not require constant and extensive management. The importance of natural enemies in this decline is vital, which is why it is extremely important to know them, conserve them and protect them.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 13, No. 3. September 2014.