Wilson Cut is the only boat channel connecting the shallow waters of Pineland with the deeper waters of Pine Island Sound. In 1925, Graham and Mary Wilson bought property at Pineland, built up the shoreline with material from midden mounds at Pineland plus off -shore sediment, and constructed their home. Today it is known as the Tarpon Lodge.

At about the same time, Graham Wilson hired local men to dig a boat channel. A resident of Pineland, Ted Smith, worked on that channel as a young man. He said, “We dug nine feet of solid rock out of that channel, to make the channel thirty feet wide. Under that nine-foot layer of rock we dug up pine trees that big around [indicating about three feet] with bark on them.”

Where did the trees come from and how long were they there? How much time does it take for nine feet of limestone to solidify? Perhaps we can find a clue by looking at the geology of Pine Island Sound.

The Geology of Pine Island Sound

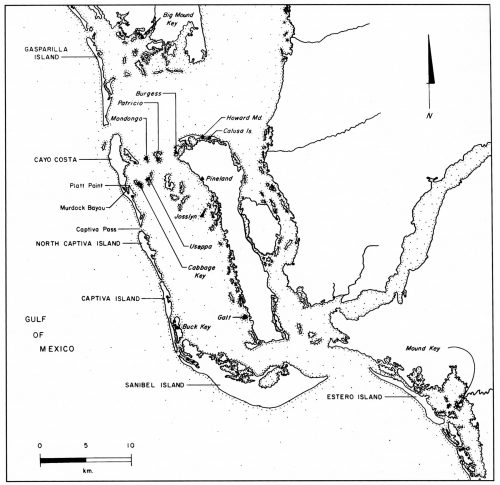

Visitors to the Calusa Heritage Trail at Pineland are treated to a magnificent panorama of Pine Island Sound from the summit of the Randell Mound. Distant gray-green islands frame the view of the Gulf of Mexico through Captiva Pass, six miles away.

The Gulf of Mexico is 150 million years old. It submerses more than half of the gently sloping west side of Florida’s continental shelf before it reaches Pine Island. This continental shelf was rifted from the margin of the African continent (at Senegal) during the Triassic period about 200 million years ago. Then in the early Jurassic, the Gulf of Mexico opened as North America separated from South America. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans fl owed together near the Gulf until the Isthmus of Panama closed about two million years ago. Then elephants, camels, horses and other animals spread from continent to continent, leaving interesting fossils in the Peace River valley. On rare occasions today, worked fossils are found in the archaeological sites of Pine Island Sound; for example, fossilized sharks’ teeth, drilled by indigenous people, and a fossilized dugong rib with wear marks indicating use as a grinder or pounder.

About 14500 B.C. the water level of the Gulf of Mexico was low, and the dry land mass of Florida was twice as wide as it is today. Upland forests grew along the ancient riverbeds and tributaries of what are today the Peace and Myakka Rivers. The highest points on Useppa Island, Cabbage Key, Patricio Island, and Burgess Island were once high sand dunes along these rivers. The Gulf was at least another 100 miles to the west. Early Paleo-Indian people hunted on these ridges. A stone spear point dating to between 8000 and 6500 B.C. was found in 1987 on a high part of Useppa, deposited before it was an island.

As the Ice Age came to an end and ice sheets melted, sea levels rose throughout the world. By 4500 B.C. Florida had taken on the shape with which we are familiar today. The water table filtered up through the limestone of Florida. The present day Lake Okeechobee filled and became the largest lake in Florida. For the first time in history, the Caloosahatchee River flowed.

Long, narrow, wave-dominated islands grew as turbulence of tides lifted shoaling sediment at the river channels, creating the first sand bars and spits. Over the next five hundred years the western edge of what would become Pine Island Sound accumulated several beach ridges. These became the islands of Sanibel, Captiva, Cayo Costa, and Gasparilla.

At high tide, the salt water in the passes met the fresh water from three rivers, the Peace, the Myakka, and the Caloosahatchee. Thus was born the estuary, where salt water mixes with fresh water. It is one of the most biologically productive environments in the world.

The calm, shallow waters of the Sound maximized the rate of sedimentation. As drowned trees fell and the logs sank in the muck, layer upon layer of sediment covered the tree trunks. Geologists say that different types of limestone can form in either decades or centuries. The lime- stone in Wilson Cut may have solidified either rapidly or slowly over several thousand years, depending on its rate of accretion, its molecular structure, and pressure.

Dynamic forces today continue to shape the barrier islands. The approximate dates of openings and closings of the passes and the physical status of the islands in precolumbian times are inferred from evidence provided by geologists and zooarchaeologists. Species that prefer high or low salinity and live in dense populations at particular locations at given times provide clues. For example, the evidence suggests that Boca Grande Pass and San Carlos Bay were the two most ancient passes. Captiva Pass is hypothesized to have opened between A.D. 650 and 1350. Buck Key, east of today’s Captiva, may have been a barrier island until the southern end of Captiva developed a seaward promontory between A.D. 500 and 1000. Blind Pass, separating Sanibel and Captiva, may not have existed before A.D. 1340.

In more recent times, Captiva and North Captiva were united until a hurricane opened Redfish Pass in 1921. An old inlet called Packard Pass opened midway along North Captiva and was later obscured with accreted sediment. In 2004 North Captiva split again (further south) during Hurricane Charley, creating Charley Pass, which refilled within five years.

All of the west coast barrier islands are oriented north-south with one exception, Sanibel Island, which is oriented east-west. Seismic surveys show that this orientation was influenced by bedrock formations differing from that of the other islands.

All of the beach barrier islands have sand dune cores, as well as their immediate inland neighbors such as Punta Blanca, Mondongo, Patricio, Burgess Island, Cabbage Key, and Useppa. The highest sand ridges on the latter three islands may not have been submerged at all since before the last ice age.

Some of the islands of Pine Island Sound may have begun as oyster bars that grew on mud flats or sediment over limestone. For example, Part Island, about 2.5 miles due west of Pineland is the northernmost of a group of islands that appear to have been colonized by mangroves over oyster bars. The group includes Josslyn Island, and extends south to Panther Key off Pine Island Center.

Each of these islands and the estuary of Pine Island Sound have a diverse geologic, archaeological, and historical past. What Ted Smith observed was just one small part. More of this story will be told in future articles in this series.

This article was taken from the Friends of the Randell Research Center Newsletter Vol 11, No. 2. June 2012.