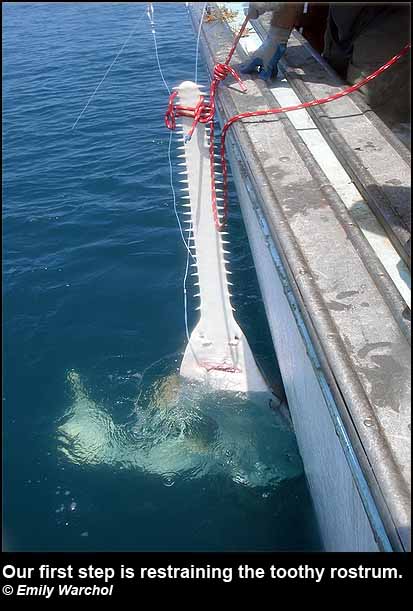

Sawfish may look somewhat like sharks, but with wide pectoral fins and flatter bodies, they are actually modified rays. Their rostrum (snout), instead of teeth, has specialized denticles which are a type of scales, that they use to stun and injure small fish before eating them. Smalltooth sawfish grow to an average of 18 feet long, 25% of which is their rostrum. They prefer bays, estuaries and rivers, but have been found in deep water and in freshwater habitats.

Habitat destruction and overfishing have succeeded in eradicating the smalltooth sawfish from the majority of its former range. The last remaining population in U.S. waters is off south Florida, a sad remnant of a population that once ranged from North Carolina to Texas. On April 1, 2003 the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service placed the smalltooth sawfish on the Endangered Species List, making it the first marine fish species to receive protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Read the entire smalltooth sawfish species profile

Habitat destruction and overfishing have succeeded in eradicating the smalltooth sawfish from the majority of its former range. Consequently, it survives in small pockets throughout its current range. The last remaining population in U.S. waters is off south Florida, a sad remnant of a population that once ranged from New York to Texas. On April 1, 2003 the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service placed the smalltooth sawfish on the Endangered Species List, making it the first marine fish species to receive protection under the Endangered Species Act. The World Conservation Union (IUCN) has also listed P. pectinata as “Endangered” throughout its range and “Critically Endangered” in the north and southwest Atlantic Ocean. Florida has also established three wildlife refuges to further protect its habitat. This new level of protection will hopefully help this unique elasmobranch recover to its previous levels of abundance within U.S. waters.

The roar of an outboard motor. The song of a humpback whale. Regardless of the source, sound waves travel five times faster underwater than they do through the air.

Scientists from the Florida Program for Shark Research (FPSR) used acoustic technology to actively track the movements of adult smalltooth sawfish, the first marine fish to be categorized as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Data gathered on behavior will better aid conservation efforts and provide insights into the life history of these elusive animals. Active tracking is one technique that provides high spatial resolution, so researchers are more confident about where sawfish are within a relatively small area.

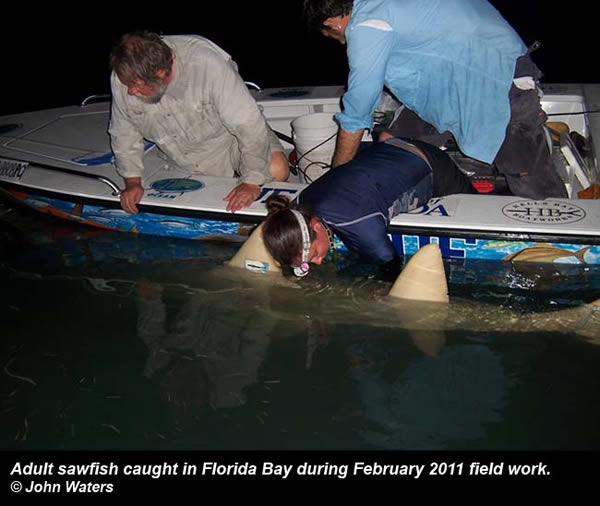

In February and March of 2011, FPSR scientists conducted two 5-day trips in Florida Bay equipping sawfish with active acoustic tags in an effort to observe short-term movements and habitat use of adult sawfish.

“No one had ever done active tracking of adult sawfish before,” said John Waters, manager of the National Sawfish Encounter Database (NSED). “It provided us with a better fine-scale resolution of their habitat use patterns.”

Active tracking requires researchers with a portable receiver, called a hydrophone, follow the tagged animal in order to collect acoustic signals. GPS points are generated in real time and researchers record the data and follow the fish as closely as possible for as long as the signal is detected. The receiver also collects information on depth and temperature.

Traditional rod-and-reel fishing was used to capture the two adult sawfish. The animals were measured and sexed before tissue samples were obtained for genetic analysis and tags were attached to the first dorsal fins. In addition to acoustic tags, dart tags (which list an animal’s ID number and who to contact if encountered) and satellite tags (to provide movement data on larger spatial and temporal scales) were used.

The signal from the first tagged sawfish was lost shortly after tagging, while the second sawfish was tracked on-and-off over a three day period.

Bethan Gillett, International Shark Attack File (ISAF) member and FPSR biologist, assisted with the tagging. “We observed that the sawfish spend more time in deeper channels during the day and then move to grass flat shallows during the night,” Gillett said. “Their eyes are a really vibrant shade of green due to tapetum lucidum- the eyes have a back like a mirror that reflects light out of the eye to add more light to the overall environment.”

According to Waters, public reports of sawfish encounters are frequent in Florida Bay and the upper Keys. This led researchers to propose locations for study that had the highest probability of capture.

In 2012, FPSR will be transitioning from active to passive tagging of sawfish. Passive tagging uses a series of underwater receivers that record acoustic feedback from tagged animals that swim within a certain distance of the receiver. Data is collected over a longer period, but with less fine scale spatial resolution.

“Active tracking is extremely labor intensive and requires researchers follow the animal continuously,” Waters said. “Passive tracking collects similar data over longer timescales and requires less involvement, and you can track more than one animal at the same time. Passive tracking is better for generating a big picture of what habitat the species inhabits, while active tracking provided higher spatial and temporal resolution.”

The reception range of both passive and active acoustic tags varies depending on underwater topography, such as hills or other landmarks, which affect sound wave movement patterns. In flat terrain, an acoustic “ping” from a tagged specimen could be picked up from a receiver as far as 500 meters-roughly a third of a mile- away.

Funding for this research was provided by a grant awarded by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

Written by MacKenzie Burger and John Waters

The smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) is an endangered marine species, closely related to guitar fish. The waters off South Florida are one of the last habitats where these remarkable creatures still thrive. Florida Program for Shark Research and Florida State University’s Marine Ecology Lab collaborate to learn more about sawfish behavior, ecology, and life history. As with many rare and endangered species, one of the biggest obstacles for those attempting to study sawfish is finding them. This month’s sampling off the Southwestern coast of Florida has been one of our most successful efforts, resulting in the capture and release of nine adult sawfish.

The team spent four days aboard “Whips N’ Fins”, a commercial shark long-lining vessel based in Key West. We set out just after day break, chopping ladyfish and baiting hooks as we moved westward towards the Marquesas. The weather was perfect to be out on the water; partly cloudy skies with calm glassy seas. Each day’s fishing consisted of 6 lines, each equipped with 100 hooks, over a distance of one mile. Soaking two lines at a time for a one hour period gives us a decent catch rate, without compromising the animals’ release condition.

Our catch consisted mostly of nurse (Ginglymostoma cirratum) blacknose (Carcharhinus acronotus), sharpnose (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae), and blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus); all common species in Florida waters. Caribbean reef (Carcharhinus perezi) and great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran), and bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) were also among the catch. There was absolutely no teleost bycatch. Once aboard, we measure, tissue sample, photograph, and dart tag all sharks, working quickly to release them alive.

The best aspect of fishing is never knowing exactly what will be caught on the line resting hundreds of meters below. The deck bustles with exhilaration as the distinctive sawfish silhouette floats up slowly towards the side of our vessel. The sawfish ranged in size from 10-14 ft long. This size class is thought to be mature, although sawfish have been known to reach lengths of up to 25 ft.

We equipped each sawfish with a high-tech satellite tag, tethered to an umbrella dart, which anchors it in the base of the dorsal fin. After several months of recording, these tags will pop off and transmit temperature, depth, and location data to a satellite. Analysis of blood, DNA, and tissue samples gives us further clues into the life history and ecology of this little known fish. Our goal is that our efforts will bring about an improved understanding of sawfish biology, with a positive influence on conservation. Thank you to all the people that continue to make this project a success. This work is conducted pursuant to Endangered Species Permit #13330.

Written by Bethan Gillett; photos by Emily Warchol