For more than 140 years, Mixodectes pungens, a species of small mammal that inhabited western North America in the early Paleocene, was a mystery. What little was known about them had been mostly gleaned from analyzing fossilized teeth and jawbone fragments.

But a new study of the most complete skeleton of the species known to exist has answered many questions about the enigmatic critter — first described in 1883 by famed paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope — providing a better understanding of its anatomy, behavior, diet and position in the Tree of Life.

The study, co-authored by Yale anthropologist Eric Sargis, demonstrates that the mature adult Mixodectes weighed about 3 pounds, dwelled in trees and largely dined on leaves. It also shows that these arboreal mammals — an extinct family known as mixodectids — and humans occupy relatively close branches on the evolutionary tree.

“A 62-million-year-old skeleton of this quality and completeness offers novel insights into mixodectids, including a much clearer picture of their evolutionary relationships,” said Sargis, professor of anthropology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, curator of vertebrate paleontology and mammalogy at Yale Peabody Museum and the director of the Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies. “Our findings show that they are close relatives of primates and colugos — flying lemurs native to Southeast Asia — making them fairly close relatives of humans.”

The study was published on March 11 in the journal Scientific Reports. Stephen Chester, associate professor of anthropology at Brooklyn College, City University of New York, is its lead author.

Illustration by Andrey Atuchin

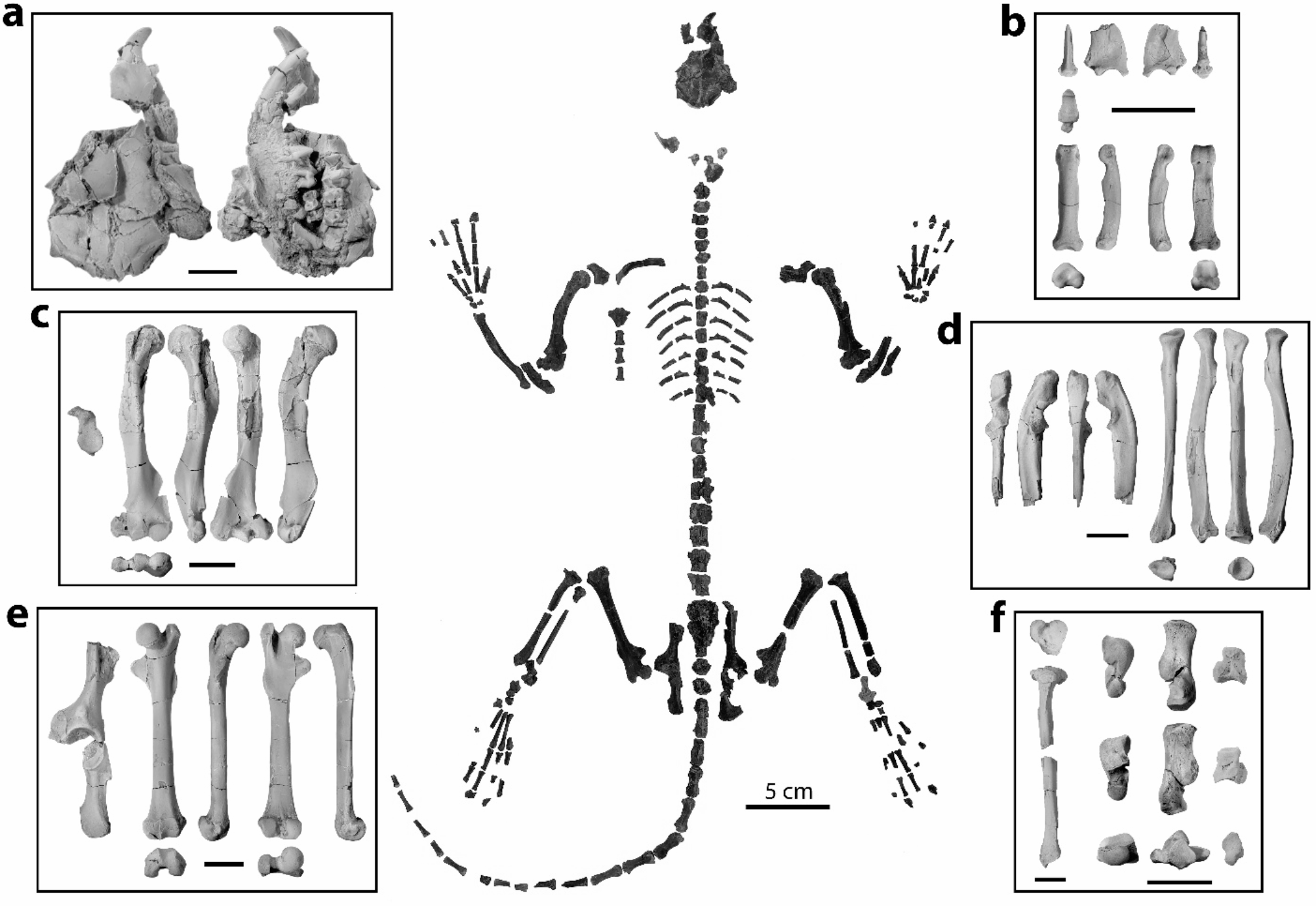

The skeleton was collected in New Mexico’s San Juan Basin by co-author Thomas Williamson, curator of paleontology at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, under a permit from the federal Bureau of Land Management. It includes a partial skull with teeth, spinal column, rib cage, forelimbs and hind limbs.

The researchers determined that the skeleton belonged to a mature adult that weighed about 1.3 kilograms, or 2.9 pounds. The anatomy of the animal’s limbs and claws indicate that it was arboreal and capable of vertically clinging to tree trunks and branches. Its molar teeth had crests to break down abrasive material, suggesting it was omnivorous and primarily ate leaves, the study showed.

“This fossil skeleton provides new evidence concerning how placental mammals diversified ecologically following the extinction of the dinosaurs,” said Chester, a curatorial affiliate of vertebrate paleontology at the Yale Peabody Museum. “Characteristics such as a larger body mass and an increased reliance on leaves allowed Mixodectes to thrive in the same trees likely shared with other early primate relatives.”

Mixodectes was quite large for a tree-dwelling mammal in North America during the early Paleocene — the geological epoch that followed the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that killed off non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the researchers noted.

For example, the Mixodectes skeleton is significantly larger than a partial skeleton of Torrejonia wilsoni, a small arboreal mammal from an extinct group of primates called plesiadapiforms, that was discovered alongside it. While Mixodectes subsisted on leaves, Torrejonia’s diet mostly consisted of fruit. These distinctions in size and diet suggest that mixodectids occupied a unique ecological niche in the early Paleocene that distinguished them from their tree-dwelling contemporaries, the researchers said.

“This animal was its own unique experiment in the evolution of early-primate-like animals,” said co-author Jon Bloch, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “It’s also just a beautiful specimen. Usually, you only get bits and pieces of these early primate-like things. You’re lucky if you get anything below the head. This skeleton is remarkably complete.”

Image by Chester et al. (2025) CC BY

Two phylogenetic analyses performed to clarify the species’ evolutionary relationships confirmed that mixodectids were euarchontans, a group of mammals that consists of treeshrews, primates and colugos. While one analysis supported that they were archaic primates, the other did not. However, the latter analysis verified that mixodectids are primatomorphans, a group within Euarchonta composed of primates and colugos, but not treeshrews, Sargis explained.

“While the study doesn’t entirely resolve the debate over where mixodectids belong on the evolutionary tree, it significantly narrows it,” he said.

Jordan Crowell of the City University of New York and Mary Silcox of the University of Toronto Scarborough are also co-authors on the study.

The study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation, the Leakey Foundation, the City University of New York, the Bureau of Land Management and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

This story originally appeared in YaleNews.

Source: Jon Bloch, jbloch@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Mike Cummings, michael.cummings@yale.edu

Media contact: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@floridamuseum.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452