After three consecutive years of worldwide declines, the number of shark bites picked up in 2021, with a total of 73 unprovoked incidents. The data, published this week by the Florida Museum of Natural History’s International Shark Attack File, also included 39 provoked shark bites and nine fatalities that occurred throughout the year.

The number of unprovoked bites in 2021 aligns with the five-year global average of 72 annually but is in stark contrast to the 52 confirmed bites recorded in 2020, which were the lowest documented in over a decade. While the exact cause of the reversal is unclear, ISAF manager Tyler Bowling attributes a portion of the trend to beach closures associated with COVID-19 restrictions.

“Shark bites dropped drastically in 2020 due to the pandemic. This past year was much more typical, with average bite numbers from an assortment of species and fatalities from white sharks, bull sharks and tiger sharks,” Bowling said.

The number of unprovoked fatal encounters with sharks also remained high in 2021, with most taking place in the South Pacific. There were six confirmed deaths in Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand, while single incidents occurred in South Africa, Brazil and the United States. Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) were characteristically the primary culprit for unprovoked fatalities.

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

While the ISAF investigates all reported shark bites, it emphasizes those that were unprovoked, which are defined as incidents which occurred in the shark’s natural habitat without human provocation. These help researchers understand the natural behavior of the animals which can help in developing mitigation measures.

The numbers at a glance

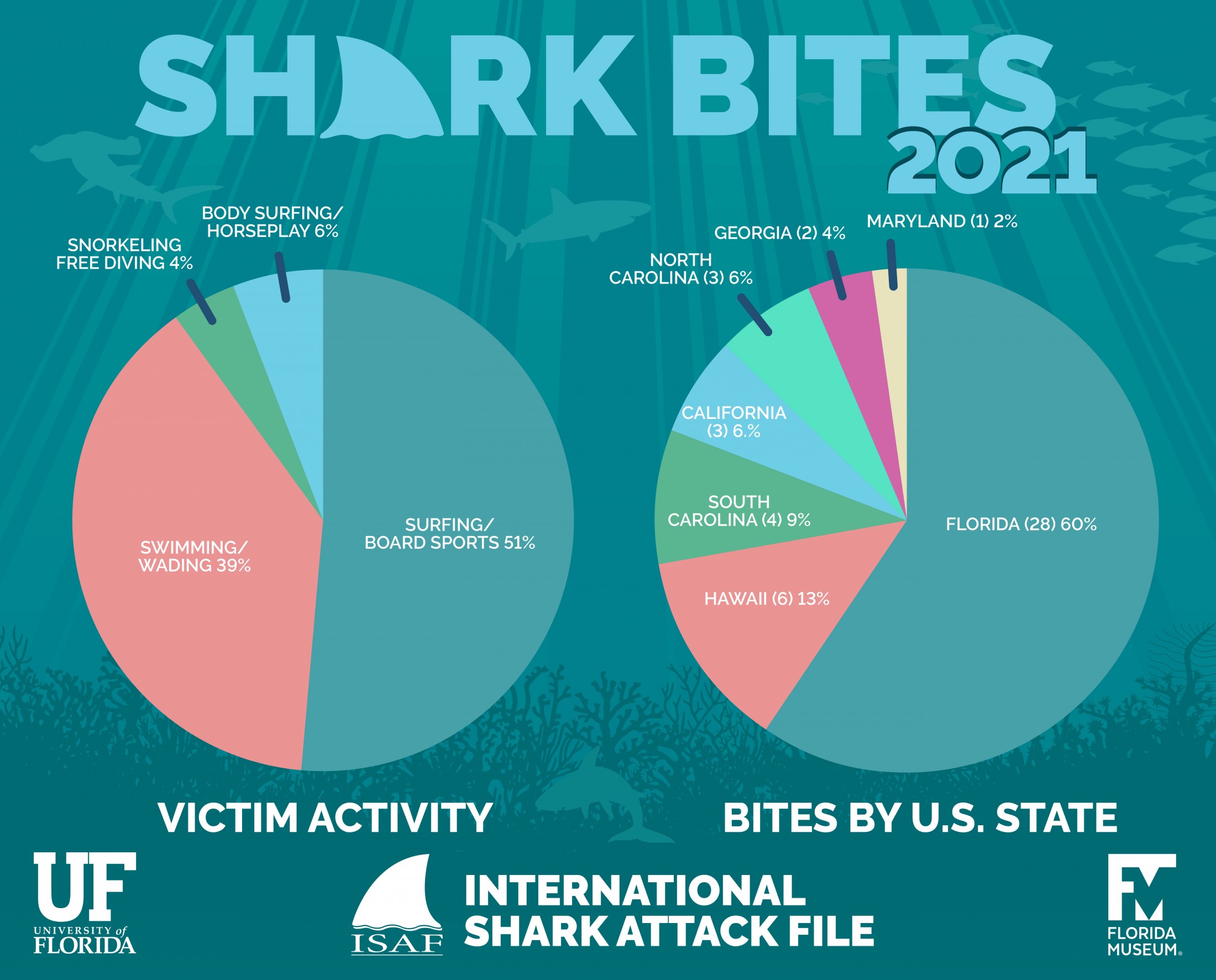

The United States continues to lead the world in the annual number of shark bites, with a total of 47 in 2021, representing 64% of global cases. Of these, all but five took place along the Atlantic Seaboard.

As in previous years, Australia had the second-highest number of bites globally, with 12 total, representing a decrease from its five-year global average of 16 bites. Australia also had three fatalities, which, although down from last year’s six, were still the highest count of any country in 2021. Brazil and New Zealand each had three bites, while Canada, Ecuador and St. Kitts and Nevis all followed with single incidents.

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

Shark bites resumed in South Africa in 2021 after zero reported incidents the year before. Great white sharks are thought to be common off the coast of Cape Town, but after a pod of orcas (Orcinus orca), which are known to prey on sharks, migrated into the region in 2017, white shark sightings became rare.

“We don’t know how often orcas kill white sharks, but when they do, they seem to have a preference for the oily liver and leave the rest. As of 2021, however, white sharks appear to have migrated east, and more are now seen along South Africa’s Wild Coast,” Bowling said. As a result, three shark bites were reported for the country in 2021, one of which was fatal.

Despite the easing of COVID-19 travel and recreational restrictions, shark-bite reporting remains spotty, as first responders and coroners continue to grapple with a high number of deaths due to the virus. As a result, the number of unconfirmed shark bites in 2021 was high for the second consecutive year, with 14 putative incidents still being investigated and one occurrence in which a designation could not be made.

Patterns in perspective

While last year saw a dramatic increase in shark bites and a high number of mortalities, both remain well within the long-term averages. As more people have flocked to warm beaches, encounters with sharks have become more common, especially in Florida, which has the second-highest rate of population growth in the United States. Yet deaths, in the long run, are becoming less frequent.

“The overall decline in mortalities from shark bites is likely due to a combination of improved beach safety protocols around the world and a diminishment in the number of sharks of various species in coastal waters,” said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum’s shark research program. “The spike in 2020 and 2021 is almost certainly because of the expanding numbers of white sharks, which have been increasing in various localities likely in response to a boom in the seal populations they feed on.”

Image by Jane Dominguez/University of Florida

The majority of individuals (51%) bitten by sharks were surfers or boarders, who spend a significant amount of time on the water in and around surf zones. This thin strip of water, where inbound waves that may have travelled for hundreds of miles finally snag on the rising coastal seafloor and topple over, creates the perfect environment for surfers and sharks alike.

Marine coasts and estuaries are a favorite feeding ground for a variety of fishes, which take advantage of the tides to scope out new food and rummage near the shallow seafloor for plants and invertebrates. These smaller fishes, in turn, attract sharks, which sometimes mistake humans for prey.

“For blacktip sharks in Florida, it’s most often a case of mistaken identity,” Bowling said.

Blacktip sharks (Carcharhinus limbatus) are likely responsible for the majority of bites in Florida, which has consistently had the highest bite count of any geographic area for the past several decades. These relatively small sharks hunt in warm waters near shorelines where they use the shallows to avoid predators of their own, including great hammerheads (Sphyrna mokarran) and bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas).

The shallow water and turbulent waves in surf zones kick up sediment that make it hard for sharks to sight their prey, Naylor explained. “About 60% of all bites we record are in low visibility water.”

ISAF provides a wide range of suggestions on how to decrease your chances of being bitten by a shark, such as avoiding splashing in open water, which sharks may mistake for struggling fish. Reflective jewelry should be avoided as well, which may glint in sunlight, resembling iridescent fish scales.

Read ISAF’s summary of 2021’s shark bites.

Sources: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954;

Tyler Bowling, tbowling2@ufl.edu, 352-273-1949