Shiny amber jewelry and a mucky Florida swamp have given scientists a window into an ancient ecosystem that could be anywhere from 15 million to 130 million years old.

Photo by David Dilcher

Scientists at the Florida Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Natural History in Berlin made the landmark discovery that prehistoric aquatic critters such as beetles and small crustaceans unwittingly swim into resin flowing down into the water from pine-like trees. Their findings were published in October 2007 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The resin with its entombed inhabitants settled to the bottom of the swamp was covered by sediment and after millions of years became amber, a bejeweled version of the tar pits that trapped sabertoothed tigers in what is now California, said David Dilcher, Florida Museum of Natural History paleo-botanist and one of the study’s researchers.

“People never understood how freshwater algae and freshwater protozoans could be incorporated in amber because amber is considered to have been formed on land,” Dilcher said. “We showed that it just as well could be formed from resin exuded in watery swamp environments. Later the swamps may dry up and the resin hardens.”

Dilcher and Alexander Schmidt, a researcher at the Museum of Natural History in Berlin, replicated the prehistoric demise of the water bugs by taking a handsaw to a swamp on Dilcher’s property near Gainesville. After they cut bark from some pine trees, the resin flowed into the water and they collected the goo and took it back to Dilcher’s lab on the University of Florida campus.

Photo by David Dilcher

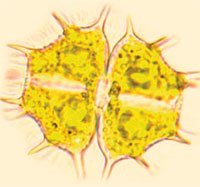

Stuck in the sticky sap were representatives of almost all the small inhabitants of the swamp ecosystem, Dilcher said. “We found beautiful examples of water beetles, mites, small crustaceans called ostracods, nematodes, and even fungi and bacteria living in the water,” he said.

The discovery not only solved the mystery of how swimming bugs could have been entombed in sticky sap from high in a tree but could lead to new information about prehistoric, maybe even Jurassic, swamps, Dilcher said. Studying organisms that were trapped for millions of years in amber may help scientists recreate prehistoric water ecosystems and learn how these life forms changed over time.

While no one is claiming the entombed bugs will be brought back to life through genetic splicing, the discovery may give clues about the evolution of microorganisms.

“We all think of horses, elephants and people as having changed a great deal through time,” he said. “Have amoeba and other microscopic organisms changed much? Or have they found a niche or what we call a stasis in which their evolutionary lineage persists for many hundreds of millions of years? We don’t have the answers to those questions until we look at the fossil record.”

Insects such as bees, tics and fleas that become embedded in amber have received a great deal of attention because they are so abundant, Dilcher said. “Unfortunately, people have overlooked the little things while searching for the big bugs and the flowers in amber.”

Microorganisms are important because they form relationships with higher organisms, making them the foundation of the pyramid of life, Dilcher said. “To understand more about their evolution adds an important step in our understanding of life itself.”

Gene Kritsky, editor of the journal American Entomologist and a biology professor at the College of Mount St. Joseph in Cincinnati, said Dilcher has performed a great service in answering a question that has long puzzled scientists, the seemingly contradictory aspect of finding aquatic insects in tree resin.

“It’s been one of the strange things mentioned by biologists and entomologists for decades – how do you account for aquatic insects and organisms in what seemed to be an ancient terrestrial environment,” Kritsky said. “Dilcher examined this contradiction by creating the conditions that would cause sap deposits to flow into water to see what would happen. The results demonstrated that aquatic insects can be trapped in resin without leaving their aquatic world. Thus, the presence of aquatic organisms in amber is the result of a simple natural process.”

Learn more about the Paleobotany & Palynology Collection at the Florida Museum.