Few people today are aware that a century and a half before there was a San Francisco in California, a San Francisco mission existed in northern Florida. San Antonio, San Diego, Santa Fe–all were missions that once served Florida Indians, just as missions with the same names were home to Indians in Texas, California, and New Mexico.

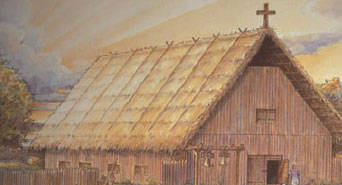

Painting by John White

The missions of La Florida, Spain’s name for the Southeastern United States, have been one of American history’s best kept secrets. Beginning in the 1560s, first Jesuit and then Franciscan friars established more than 150 missions among native peoples from Miami to the Chesapeake Bay. The largest number were in northern Florida.

By the time Spain relinquished La Florida to Great Britain in 1763 only two missions and less than 100 Indians remained. What once had been a mission system impacting the lives of thousands of native people over many generations had been destroyed.

With the removal of the Hispanic presence from La Florida memories of the missions soon faded. The wood and thatch mission buildings, like the native peoples whom they served, disappeared from the landscape. Unlike in California, Texas, or the American Southwest where a continued Spanish influence inspired public awareness of past missions and a Hispanic heritage, the missions of Spanish Florida were lost.

In the past two and a half decades archaeologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History, along with their students and colleagues, have undertaken a number of projects to learn about the lives of the Indians who lived at these missions. Across northern Florida and in southern and coastal Georgia the evidence excavated so far is remarkable, ranging from entire churches burned in rebellions and raids to inch-high religious medallions worn by Christian Indians to display their piety.

Photo by Florida Division of Historical Resources, Bureau of Archaeological Research

With new religious beliefs came new foods. Chicken and pig bones and peach pits and wheat grains excavated from mission sites represent some of the animals and plants introduced from Spain. Some mission Indians learned to speak and write Spanish and they learned prayers in Latin. Catholic rites were translated into an Indian language by one Franciscan friar. As a result, a wedding ceremony conducted in a mission church might well have incorporated words from a Native American language as well as Spanish and Latin. At San Juan del Puerto northeast of Jacksonville mission Indians were even taught to play the organ.

We now better understand the important economic contributions made by the mission Indians to the Spanish colony. These contributions, reflected in things as innocuous as thousands of excavated charred corn cobs, tell a story of crops planted, harvested, shucked, ground into meal, and transported to St. Augustine on the backs of Indians to feed the Spanish townspeople. Native workers regularly traveled to St. Augustine to work in agricultural fields and to provide labor for projects in that town. The Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine’s stone fort which still looms over the city today, was built with native labor.

Nearer the missions Indians worked to repair roads, build stream crossings, and man canoes used to ferry travelers across the St. Johns and other rivers. There even was an Indian militia, called up to help defend St. Augustine at times of military crisis. It is no exaggeration to say that the Spanish colony rested on the backs of the mission Indians.

Florida Division of Historical Resources, Bureau of Archaeological Research, Mission San Luis.

Most of the missions were destroyed in the late 17th and early 18th century when Carolinian militia and their Indian allies, as well as other Indian raiders, attacked the Georgia coastal and north Florida missions. Hundreds of mission Indians were killed or taken captive. Others fled, some to refugee mission villages outside St. Augustine. The surviving Indians were moved to Cuba in 1763.

Historical archaeology is a powerful tool which can give voice to people of the past, including the Spanish friars and the Indians who together labored at the missions of Spanish Florida.

Jerald T. Milanich is curator in archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History and author of Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians.