Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

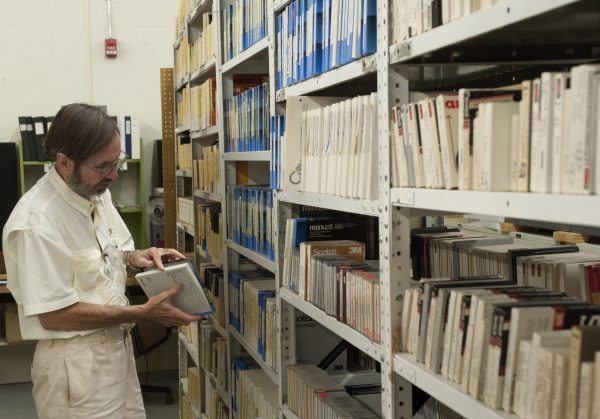

While standing next to a shelf filled with thousands of aging reel-to-reel and other tape recordings of bird sounds collected over the past 40 years, Florida Museum of Natural History ornithologist Tom Webber inspected an especially fragile reel from the 1960s.

“Eventually, even the magnetic plastic tapes will break down,” Webber said. “They’re stored under optimal conditions. But the older ones,” he said as he paused, running his hand across a stack of worn, discolored tapes, “We’re already having that happen to some of them.”

In an effort to preserve the second-largest collection of bird sounds in terms of species in the Western Hemisphere, scientists acquired a $446,000 National Science Foundation grant in 2009 to digitize the Florida Museum’s analog bird-sound field recordings, which represent more than 3,000 species. From the extinct Dusky Seaside Sparrow to vocal Florida Scrub-Jays, the complete online collection will soon provide access to more than 30,000 individual sounds.

“When we collected these sounds, we didn’t necessarily know how they would be used,” Webber said as he lifted a heavy 40-year-old sound recorder that he once lugged up and down the hills of Southern California as a student at the University of California. “But that’s the beauty of museum collections; we knew that someday researchers would be seek them out to answer questions that may not have even been proposed at the time they were recorded.”

With habitat loss worldwide, especially in the tropics, Museum ornithologists were anxious to digitize the collection as quickly as possible. In these troubled times for the environment, Florida Museum ornithology curator David Steadman said places that once were forests have fallen to agricultural development and human population growth, and many birds that once lived in the forests are also gone.

“In many ways, our sound recordings are like a library of what used to be,” Steadman said. “The collection is important not only from the standpoint of knowing what bird calls came out of a particular area where a forest used to exist, but it’s also important for conservation and restoration efforts.”

However, this rare, invaluable, collection of sounds was at risk due to the break down of oxide coating on tapes and the bleeding through of magnetized recording patterns to adjacent segments of tapes.

The Florida Museum’s bird sounds were in desperate need of preservation.

The digitization project involved more than 2,200 reel-to-reel and cassette tapes of assorted sounds, with a primary focus on New World birds. The tapes were shipped over the course of three years to the Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics at Ohio State University to be digitized. The Borror Lab, a pioneer in the process of converting analog tape collections to digital format, was instrumental in the success of the project, Webber said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Prior to 2009, information cards for each recording indicated which tape or reel contained individual calls. Requests required that someone find and cue the needed reel and then make a digital recording of the specific bird sound, Webber said. The process was not only time-consuming, but excessive handling reduced the tapes’ sound quality and became an added threat to the collection.

Digitization has preserved the sounds and provided researchers and bird enthusiasts with worldwide online access.

“Our collection makes it possible for researchers to compare hundreds or even thousands of sounds and see how they vary,” Webber said. “Museum collections such as this answer can help questions that would otherwise be logistically impossible to answer.”

The push toward digitization was largely influenced by Webber’s drive to preserve and continue the work of his mentor, John William (Bill) Hardy, the Museum’s curator of ornithology and bioacoustics from 1973 to 1995. Hardy, a jazz aficionado who owned a recording company, was the first to take advantage of the relatively portable sound equipment of the 1960s that made it possible to capture bird sounds in the field. While at Occidental College in Los Angeles, he began a comprehensive collection of bird sounds. In 1973, he came to the Florida Museum, along with Webber, and brought his collection with him.

For more than 30 years, Webber has contributed to the ever-growing collection by amassing field recordings of Jays, including the Unicolored Jay—which appears to have the largest variety of calls of any species in the crow family. His recordings are not only sounds recorded in space, but most include the behavioral context Webber observed, such as whether a particular call belongs to an adult building a nest, or a juvenile begging for food. Florida Museum ornithology curator David Steadman said Webber’s keen ear has added to the significance of many of the recordings.

“A sound recordist might target a certain species, but more often then not there’s other species in the background,” Steadman said. “Tom’s critical ear and time spent listening to and documenting those sounds has made many of the recordings even more valuable.”

Vocal cues are important for species recognition, Steadman said. If two birds look similar, but speak different languages, the two birds will recognize each other as separate species.

“Sound recordings can be used as vouchered specimens for taxonomic study,” Steadman said. “This is why field research is important to the understanding of what makes a species.”

The collection is especially important to the study of more than 200 species of nocturnal birds included in the collection, such as owls, which are more often heard than seen. As time goes on and nature changes, so do the calls of birds. But every sound in the collection is a verifiable snapshot of a short-lived reality, Webber said.

“Because birds can learn new sounds, we expect that the sounds we have will change over time and our collection will serve as a benchmark,” he said. “This will allow researchers to study the evolution of bird sounds.”

It is unclear why some birds learn new sounds and develop huge vocabularies, while others have small ones, Webber said. The Unicolored Jay, for example, has a huge variety of calls that sometimes blend into one another and range from harsh blasts of noise to melodious piping tones. Solving these kinds of puzzles is part of what draws people to the science of birds, he said, though it is also about a deeper connection with nature and an immense range of appreciation for our winged co-inhabitants of Earth.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“At a young age, I fell in love with birds for the aesthetics,” Webber said. “I was attracted to their sounds, and the places where they live.”

The study of birds is a solitary sort of passion, with scientists often going alone to research different species, but many share the fervor for a diversity of reasons. People also become interested in the discipline in a variety of ways, Steadman said.

“Some people might not even know they have a passion for birds until they’re out in the field and put on the headphones for the first time—that’s when they get it,” he said. “For me, my first word was ‘bird’ and I never looked back.”

Whether innate or developed through life experiences, those at the Florida Museum who built the bird sounds collection from the ground up aimed to make their passion accessible to the world. As knowledge of birds becomes more easily attainable, they hope people will become more concerned about protecting birds and other wildlife, Steadman said.

For some species, it is already too late.

The Dusky Seaside Sparrow, which inspired musical arrangements, was a songbird common in the Florida marshes of Merritt Island and along the St. John’s River. Habitat loss, pollution and pesticides caused the sparrow’s population to decline to only one bird named “Orange Band,” which died in 1987.

The Florida Museum’s collection contains the only known recording of the Dusky Seaside Sparrow’s song. The Museum’s bird sound database is available online at https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/bird-sounds/.

Learn more about the Ornithology Collection at the Florida Museum.