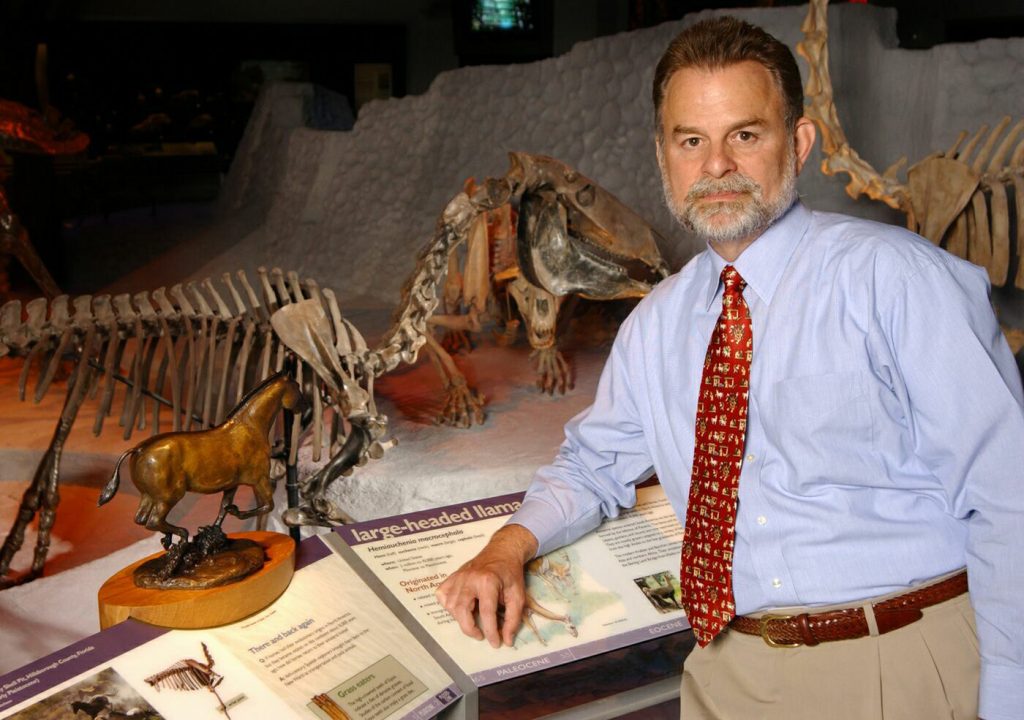

In 1977, Bruce MacFadden accepted a curatorial position with the Florida Museum of Natural History’s vertebrate paleontology collection. Since then, he has transformed the museum and made significant contributions to the fields of paleontology and science education.

Now, after 47 years, MacFadden has retired. He takes with him the title of longest-serving staff member at the museum. During his extended tenure, he has published more than 200 scientific articles, mentored over 30 graduate students and launched several science education initiatives for K-12 teachers and students.

MacFadden is a world-renowned expert on horse fossils and evolution and has maintained an active research lab while also variously serving as the museum’s head of exhibits and public programs, founding director of the Thompson Earth Systems Institute (TESI), director of education and outreach for iDigBio and much more.

Florida Museum photo by Eric Zamora

“There’s not an area of the museum that he hasn’t touched, and he is a very well-rounded, total professional. He really epitomizes what it means to be a museum scientist and a professor of distinction,” said Doug Jones, director of the Florida Museum. The two have been friends since Jones was hired as the museum’s curator of invertebrate paleontology in 1985. “Bruce has never been afraid to take risks, and, consequently, his academic career has evolved as he pursued diverse scientific questions and explored a variety of leadership roles at the museum.”

Branching out into new disciplines has been a long-running motif in MacFadden’s career.

“If you don’t take risks, you’re going to stay in your comfort zone. You’re always going to do the same thing,” MacFadden said. “If you try something that somebody hasn’t done before, that’s a risk because it might not succeed. But if you are able to make it succeed, then you’ll have breakthroughs.”

An ever-shifting path and uncertain beginnings

MacFadden was born and raised in suburban New York and was the first member of his immediate family to earn a college degree. His stepfather and his mother recognized his interest in science and encouraged him to follow his ambition.

He enrolled at Cornell University, intending to be a pre-med student. “But then I took courses in paleontology. And I just realized I didn’t want to be a doctor anymore. I wanted to be a paleontologist.”

After this realization, he focused his senior thesis on fossil fishes and attended Columbia University for graduate school. His doctoral research combined fossil vertebrates with paleomagnetism, the study of changes in earth’s magnetic field throughout time.

He was able to determine the age of fossils by measuring the magnetic polarity of the rocks they were embedded in. This approach was novel at the time, and his dissertation was one of the first of its kind.

After obtaining his doctoral degree, he took an instructor’s position at Yale University for a year. At the time, the Florida Museum already had a curator of vertebrate paleontology. But the museum’s director, Joshua Dickinson, recognized the collection’s high potential for public interest and began the search for a second curator.

MacFadden was attracted by the museum’s growing reputation and its abundant collection of Cenozoic fossils. He was hired in 1977, and for a number of years, he worked alongside David Webb, former distinguished research curator of vertebrate paleontology and University of Florida professor.

Two decades later, Jones invited MacFadden to become associate director for the museum’s new exhibit hall, a position in which he would oversee all public programs and displays. MacFadden obtained several collection improvement grants from the National Science Foundation (NSF) during his time as director and remained in that position until all the exhibits were fully constructed and filled.

Exploring new avenues in education and broader impacts

MacFadden later served as a grant reviewer and then temporary program officer for the National Science Foundation. These experiences sparked his interest in the concept of broader impacts of science on society.

In fact, he was so interested that he later wrote a book on the ways in which scientists can support their communities and contribute to public education. These experiences led to even more opportunities.

“Doug knew I was interested in broader impacts. ‘So,’ he said, ‘Would you like to be the director of TESI and put your stamp on it?’ That, again, was a risk because I was doing fine, doing my research and curating. But that was a new opportunity,” MacFadden said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

One of the Thompson Earth Systems Institute’s (TESI) key purposes is to translate scientific research and disseminate it for the benefit of society and to teach the public about earth’s natural systems. MacFadden developed a vibrant program of activities for the institute and a core team of staff that was dedicated to its mission. He also launched TESI’s grants program to fund projects aimed at communicating earth systems research to broader audiences.

In 2018, MacFadden was awarded a large grant by the University of Florida created to fund big ideas and moonshot projects. Inspired by his recent experiences in education, he created the Scientist in Every Florida School program (SEFS), which aims to connect every public school in Florida with a scientist at least once a year. “Everybody should have an opportunity to learn and succeed,” he said.

His time with the NSF also sparked his interest in informal science education — learning that takes place in museums and community spaces, rather than the traditional K-12 classroom. This was a regular topic of discussion between MacFadden and Jones.

“I could write another paper, and perhaps 12 scientists in the world might read it. Or I could put that same amount of effort into working with school teachers,” Jones said, recounting an old conversation shared with MacFadden. “Every one of those school teachers probably sees 30, 60, 90 kids a day. And if the teachers got excited about science topics, and they could infect those students with that enthusiasm, that makes the impact of what you’re doing grow so much faster.”

One of the most momentous projects MacFadden developed and oversaw during his career was a series of fossil excavations along the banks of the Panama Canal. Beginning in 2007, the canal underwent an historic expansion, giving paleontologists a once-in-a-life-time opportunity to collect in areas that would otherwise have been inaccessible.

“We got a large National Science Foundation grant in 2010 to study the Isthmus of Panama. And that’s where I learned that I enjoy working with teachers,” he said. “We brought high school teachers to Panama with us, and they helped collect fossils.” Upon returning, teachers took what they’d learned and integrated it into their classroom curricula.

One of the participants who joined the canal expedition was Stephanie Killingsworth, who was a Florida middle school science teacher at the time. It was a formative experience, so much so that she decided to pursue a master’s and Ph.D. in paleontology. She is currently finishing up her dissertation on fossil horse research as MacFadden’s final PhD student.

“Doing the workshops with Bruce sparked my curiosity again and the desire to think like a scientist,” Killingsworth said. “Bruce has been a real mentor, advisor and pillar to me in my career, both professionally and academically.” Killingsworth is also the education and outreach coordinator for the Scientist in Every Florida School program.

In 2011, MacFadden became the director of education and outreach for iDigBio, an NSF-funded biorepository for the nation’s natural history specimens. In an interview with Jill Holliday, former executive director of the iDigBio e-newsletter, MacFadden discussed his excitement about the prospect of iDigBio being used for citizen science and the problem of “dark data”—collection data that no one has access to due to lack of infrastructure. “The wonderful thing about iDigBio is that it is revolutionizing access to museum specimens,” he said.

Looking back with gratitude and forward to new horizons

MacFadden looks back fondly on his time here. “The Florida Museum of Natural History has been a great place for me to develop my career. I’ve been here for 47 years, and although I’ve had a couple of chances to leave, none were even close to being as good as staying here.”

He is especially grateful for the people who he has worked with. He gives credit to Jones, who has played a major role in his career development. “It’s widely regarded that Doug is the best university natural history museum director in the United States. We have strong, effective leadership and really fabulous faculty and staff that develop the collections. We were a very strong unit.”

Advait Jukar will assume the role of assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology beginning in August.

After retirement, MacFadden plans to take a year off and wrap up his current project on artificial intelligence (AI) and fossil sharks. He looks forward to having the time and freedom to travel with his family.

Source: Bruce MacFadden, bmacfadd@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Doug Jones, dsjones@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Stephanie Killingsworth, skillingsworth@floridamuseum.ufl.edu

Writer: Makena Lang, makenalang@ufl.edu