About 100 million years ago, a group of trendsetting moths started flying during the day rather than at night, taking advantage of nectar-rich flowers that had co-evolved with bees. This single event led to the evolution of all butterflies.

Scientists have known the precise timing of this event since 2019, when a large-scale analysis of DNA discounted the reigning hypothesis that pressure from bats prompted the evolution of butterflies after the extinction of dinosaurs.

Now, scientists have discovered where the first butterflies originated and which plants they relied on for food.

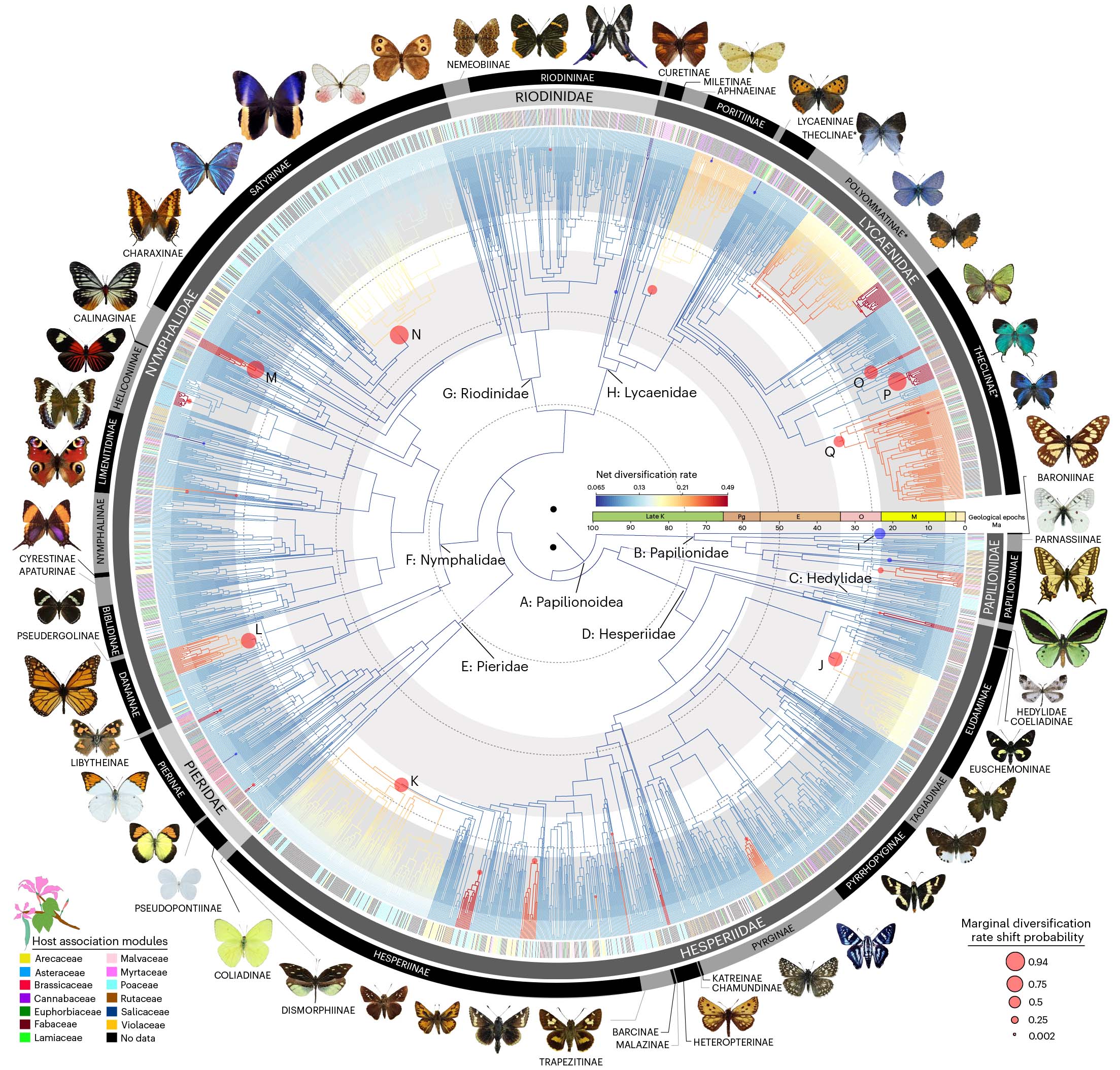

Before reaching these conclusions, researchers from dozens of countries had to create the world’s largest butterfly tree of life, assembled with DNA from more than 2,000 species representing all butterfly families and 92% of genera. Using this framework as a guide, they traced the movements and feeding habits of butterflies through time in a four-dimensional puzzle that led back to North and Central America. According to their results, published today in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, this is where the first butterflies took flight.

For lead author Akito Kawahara, curator of lepidoptera at the Florida Museum of Natural History, the project was a long time coming.

“This was a childhood dream of mine,” he said. “It’s something I’ve wanted to do since visiting the American Museum of Natural History when I was a kid and seeing a picture of a butterfly phylogeny taped to a curator’s door. It’s also the most difficult study I’ve ever been a part of, and it took a massive effort from people all over the world to complete.”

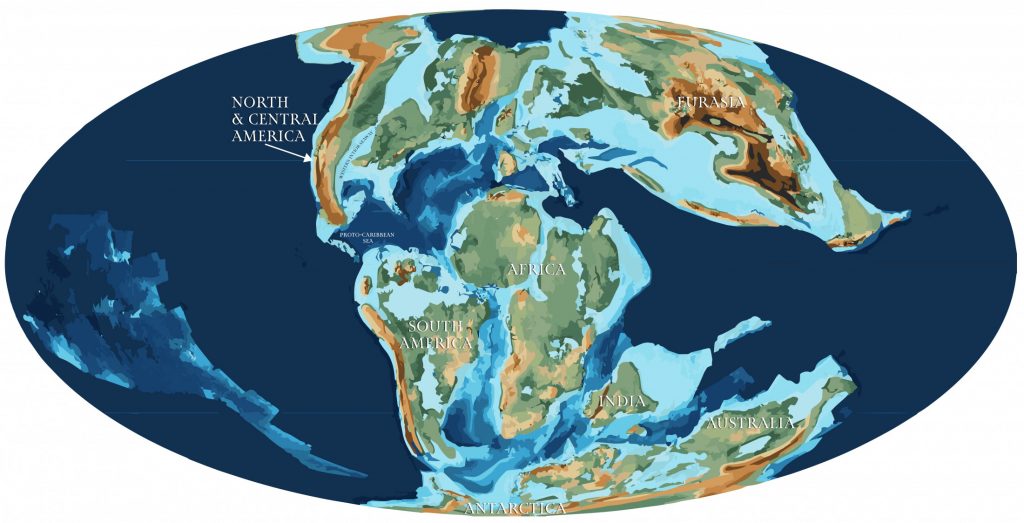

Figure by Kawahara et al., 2023 (CC BY 4.0)

There are some 19,000 butterfly species, and piecing together the 100 million-year history of the group required information about their modern distributions and host plants. Prior to this study, there was no single place that researchers could go to access that type of data.

“In many cases, the information we needed existed in field guides that hadn’t been digitized and were written in various languages,” Kawahara said.

Undeterred, the authors decided to make their own, publicly available database, painstakingly translating and transferring the contents of books, museum collections and isolated web pages into a single digital repository.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Underlying all these data were 11 rare butterfly fossils, without which the analysis would not have been possible. With paper-thin wings and threadlike, gossamer hairs, butterflies are rarely preserved in the fossil record. Those that are can be used as calibration points on genetic trees, allowing researchers to record the timing of key evolutionary events.

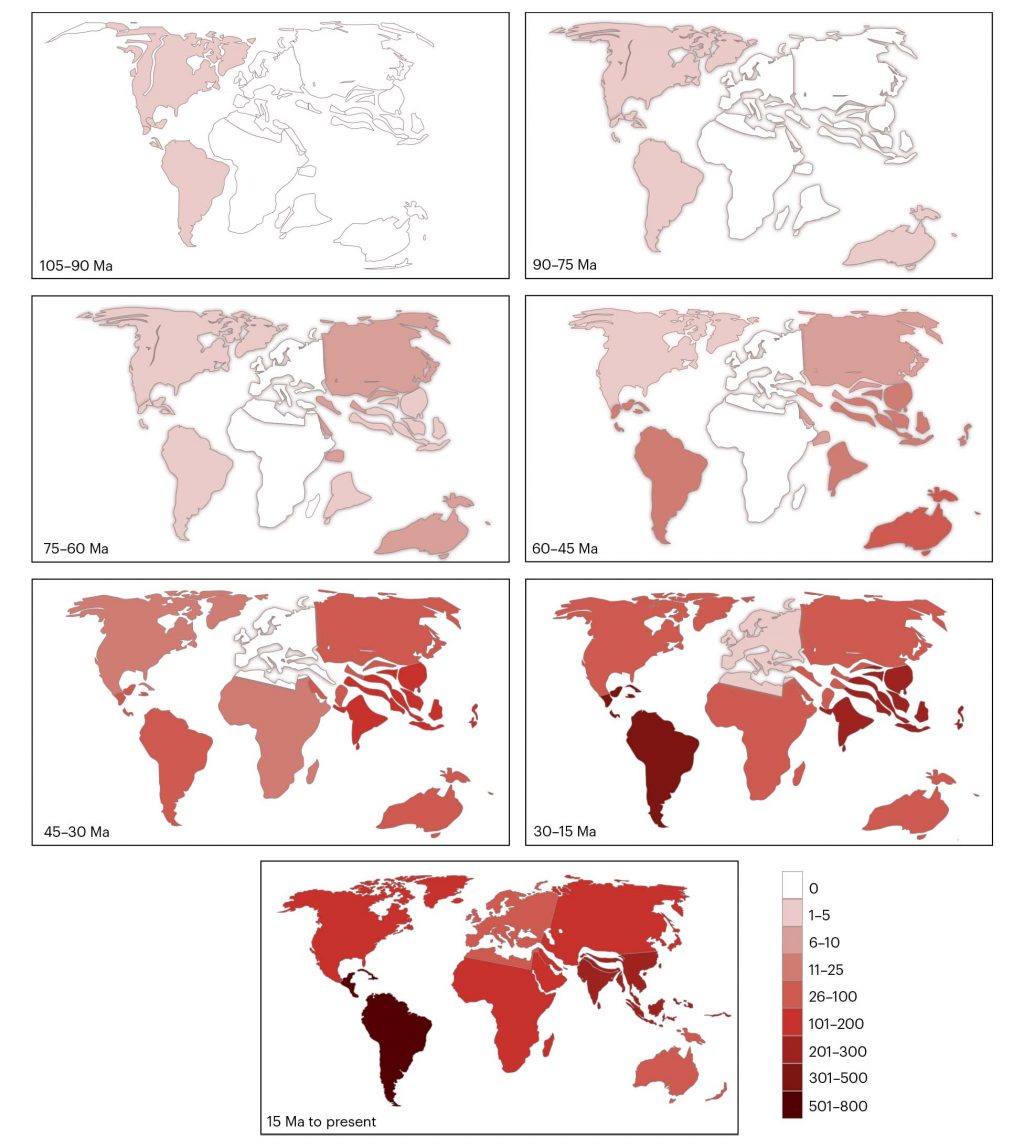

The results tell a dynamic story — one rife with rapid diversifications, faltering advances and improbable dispersals. Some groups traveled over impossibly vast distances while others seem to have stayed in one place, remaining stationary while continents, mountains and rivers moved around them.

Butterflies first appeared somewhere in Central and western North America. At the time, North America was bisected by an expansive seaway that split the continent in two, while present-day Mexico was joined in a long arc with the United States, Canada and Russia. North and South America hadn’t yet joined via the Isthmus of Panama, but butterflies had little difficulty crossing the strait between them.

Despite the relatively close proximity of South America to Africa, butterflies took the long way around, moving into Asia across the Bering Land Bridge. From there, they quickly covered ground, radiating into Southeast Asia, the Middle East and portions of eastern Africa. They even made it to India, which was then an isolated island, separated by miles of open sea on all sides.

Even more astonishing was their arrival in Australia, which remained sutured to Antarctica, the last combined remnant of the supercontinent Pangaea. It’s possible butterflies once lived in Antarctica when global temperatures were warmer, making their way across the continent’s northern edge into Australia before the two landmasses separated.

Farther north, butterflies lingered on the edge of western Asia for potentially up to 45 million years before finally migrating into Europe. The reason for this extended pause is unclear, but its effects are still apparent today, Kawahara explained.

“Europe doesn’t have many butterfly species compared to other parts of the world, and the ones it does have can often be found elsewhere. Many butterflies in Europe are also found in Siberia and Asia, for example.”

Once butterflies had become established, they quickly diversified alongside their plant hosts. By the time dinosaurs were snuffed out 66 million years ago, nearly all modern butterfly families had arrived on the scene, and each one seems to have had a special affinity for a specific group of plants.

“We looked at this association over an evolutionary timescale, and in pretty much every family of butterflies, bean plants came out to be the ancestral hosts,” Kawahara said. “This was true in the ancestor of all butterflies as well.”

Bean plants have since increased their roster of pollinators to include various bees, flies, hummingbirds and mammals, while butterflies have similarly expanded their palate. According to study co-author Pamela Soltis, a Florida Museum curator and distinguished professor, the botanical partnerships that butterflies forged helped transform them from minor offshoot of moths to what is today one of the world’s largest groups of insects.

“The evolution of butterflies and flowering plants has been inexorably intertwined since the origin of the former, and the close relationship between them has resulted in remarkable diversification events in both lineages,” she said.

Funding for the study was provided in part by the National Science Foundation (grant nos. DEB-1541500, 1541557, 1541560, DBI-1349345, 1601369, DEB-1557007, IOS-1920895, DEB- 1120380, DBI-1256742, DEB-0639861, SES-0750480, DEB-0447244 and DEB-9615760), the National Geographic Society, the Research Council of Norway (grant no. 204308), the Hintelmann Scientific Award for Zoological Systematics, the European Research Council (grant no. 851188), the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant nos. PID2019- 107078GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, PID2020- 117739GA-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and RYC2018-025335-I), the Russian Science Foundation (grant 19-14-00202), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant nos. 19916010, 13010131, 23570111, 26440207, 17K07528 and 21H02215), the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (grant nos. 563332/2010-7 and 304273/2014-7) and the Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Sources: Akito Kawahara, kawahara@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Pamela Soltis, psoltis@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452