Archaeologists have unearthed a rare trove of more than 80 metal objects in Mississippi thought to be from Hernando de Soto’s 16th-century expedition through the Southeast. Many of the objects were repurposed by the resident Chickasaws as household tools and ornaments, an unusual practice at a time when European goods in North America were few and often reserved for leaders.

The researchers believe Spaniards left the objects behind while fleeing a Chickasaw attack that followed frayed relations between the two groups in 1541. The victors took advantage of the windfall of spoils – ax heads, blades, nails and other items made of iron, lead and copper alloy – modifying many of them to suit local uses and tastes. Chickasaw craftspeople turned pieces of Spanish horseshoes into scrapers, barrel bands into cutting tools and bits of copper into jingling pendants.

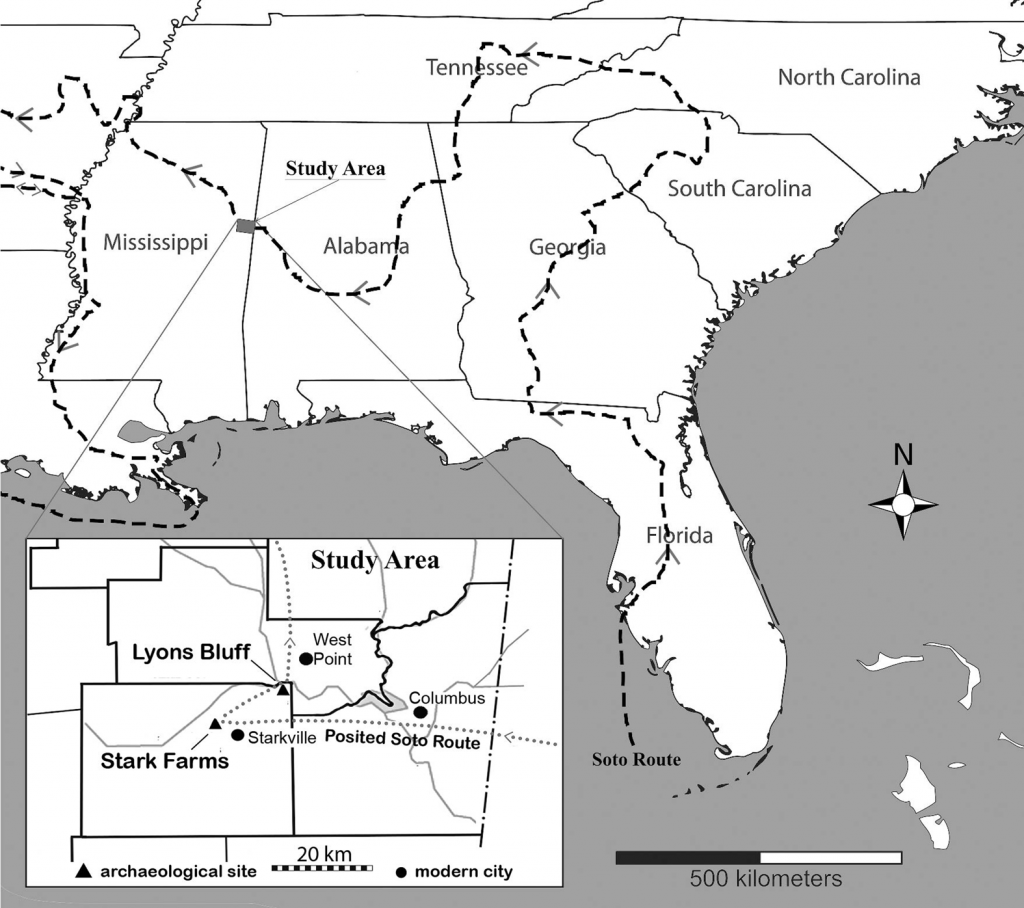

The sheer abundance of objects from the site, an area of northeastern Mississippi known as Stark Farms, is one of the factors that makes the find unique, said Charles Cobb, the study’s lead author and Florida Museum of Natural History Lockwood Chair in Historical Archaeology.

“Typically, we might find a handful of European objects in connection with a high-status person or some other special context,” Cobb said. “But this must have been more of an open season – a pulse of goods that became widely available for a short period of time.”

If the researchers’ diagnosis is correct, Stark Farms is only the second place to yield convincing archaeological evidence of direct contact with de Soto’s expedition, after the historic site of the Apalachee capital of Anhaica in present-day Tallahassee, Cobb said.

‘Unconquered and unconquerable’

By the time de Soto arrived in Mississippi in 1540, the conquistador had trekked through the Southeast for more than a year with about 600 people, hundreds of horses and pigs and heavy equipment in tow. A shrewd man with a reputation for bloodshed, de Soto was previously a key figure in the Spanish destruction of the Inca Empire in South America and came to Florida with an eye to further increase his wealth. Finding little gold, he pressed deeper into the interior, alternately befriending and warring with the Native Americans he encountered.

Map courtesy of Timothy D. Pieper/South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology

The Spaniards began on a friendly, if aloof, footing with the Chickasaws, whose leader, known as Chikasha Minko, gave them a modest village in which to spend the winter. But tensions rose as the months dragged on: De Soto executed two Chickasaws and cut off the hands of another accused of stealing pigs. The Chickasaws, who farmed maize in the region’s rich prairie soil, also must have grown tired of providing food and shelter for such a large encampment of uninvited guests, Cobb said.

With spring drawing near, de Soto demanded that Chikasha Minko provide him with hundreds of Chickasaws to carry the Spaniards’ equipment to their next destination. According to Spanish accounts of the expedition, the conversation did not go well.

Shortly afterwards, the Chickasaws launched a surprise attack under the cover of night, torching the Spanish camp and killing at least a dozen men, as well as many horses and pigs. The retreating Spaniards set up another camp about a mile away, where they were assaulted a second time. Better prepared, they fought back, but soon picked up and headed north, having lost much of their livestock, clothing and goods.

Meanwhile, the Chickasaws collected from the battlefield dozens of prized metal objects, usually reserved by the Europeans for strategic trades or as gifts to smooth relationships with local leaders.

“It’s kind of like inflation,” Cobb said. “You don’t want too much stuff to get out or that gift will be devalued. That’s what makes this site unusual.”

After the Chickasaws sent the Spanish packing, the region remained largely free of European presence for nearly 150 years.

“This research shows how Chickasaws adapted to invasion by alien intruders and secured their reputation as unconquered and unconquerable,” said study co-author Brad Lieb, director of Chickasaw archaeology for the Chickasaw Nation’s Heritage Preservation Division. “The findings are remarkable in their success in addressing a baseline event in Chickasaw cultural history – the first encounter with Hernando de Soto and the Spanish invaders.”

History confirmed by metal detectors

Photo courtesy of James B. Legg/South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology

When Cobb, Lieb and their colleagues first arrived at Stark Farms in 2015, they weren’t just looking for traces of de Soto. The Chickasaw Nation, removed from its traditional homeland to Oklahoma by the U.S. Department of War in 1837, had commissioned the team to identify and preserve ancestral sites and provide Chickasaw university students the opportunity to reconnect with their heritage through an archaeology fieldwork program.

The team focused on studying the environmental factors in the movements of Native Americans across the landscape, where radiocarbon dates showed people had lived since the 14th or 15th century. Curious about early residents’ potential interactions with outsiders, the researchers brought metal detectors, a speedy way of finding objects of European origin. The first day they deployed the detectors, the machines began pinging. Soon, the team was uncovering dozens of items, including a small cannon ball, a mouth harp and what could be a Spanish bridle bit, emblazoned with a golden cross.

“We couldn’t believe it,” Cobb said. “There was a lot of serendipity for sure.”

The style and type of objects, as well as their location, aligned with Spanish accounts of the de Soto expedition and the 1541 battle at Chikasha, the main Chickasaw town. But the researchers found no evidence of a burned village or the remains of horses and pigs. Cobb said the site was likely a village near Chikasha, whose inhabitants visited the site of the conflict and brought items back to their households. They may also have acquired some of the objects during the previous winter through under-the-table trading with Spanish soldiers.

The Chickasaws generally relied on bone, cane or stone as raw materials for their cutting and scraping tools, making the haul of metal a particular boon. While some of the objects retain their original form, the Chickasaws painstakingly reworked others into more familiar shapes. They bent metal back and forth until it broke and ground down and smoothed edges, modifying tools to mimic the design of their traditional Chickasaw counterparts.

“One of the most stunning things we’ve found is an exact iron replica of a Native American stone celt, or ax head,” Cobb said. “I’ve never seen anything like this in the Southeast before.”

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Among the more sobering finds were chain links, pulled apart with sharpened edges. “The Spanish brought reams of chain with them to shackle Native Americans as captives and porters,” Cobb said. “This is evidence of some of the first examples of European enslavement of people in what is now the U.S.”

The refashioned items from Stark Farms represent a stage of Native American experimentation and improvisation with foreign items that largely faded by the late 1700s and 1800s, as they folded European materials and technology more completely into their own.

“In the 1500s, a thimble might be turned into a bangle. By the late 1700s, a thimble is a thimble,” Cobb said. “You tend to see a more regular adoption of goods over time.”

Spanish survivors did their own repurposing

De Soto failed to establish any permanent settlements in the Southeast, joining a line of ill-fated expeditions that demonstrated the precariousness of Europeans’ early attempts to dominate the region. He succumbed to a fever on the banks of the Mississippi River in 1542, and his remaining band of men made rafts and floated south to Mexico where they found passage back to Spain.

There, they undertook a repurposing effort of their own: Having failed to find fame and fortune in the Americas, they sold their stories, many of which became bestselling books, Cobb said.

“There was a thriving industry in explorer and survival tales, which is probably one of the reasons why some of these individuals provided their accounts. From that perspective, it was very modern.”

The researchers published their results in American Antiquity.

The objects will be repatriated to the Chickasaw Nation for permanent curation and exhibits.

James Legg, Steven Smith and Chester DePratter of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology and Edmond Boudreaux of the University of Mississippi also co-authored the study. The Chickasaw Nation reviewed the study for consistency with its histories.

The Chickasaw Nation and its Chickasaw Explorers Program co-led and funded the research. Portions of the fieldwork were also funded by the National Geographic Society.

Sources: Charles Cobb, ccobb@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1916;

Brad Lieb, brad.lieb@chickasaw.net

Writer: Natalie van Hoose, nvanhoose@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1922