A small tooth fragment plucked from a 13-year-old boy’s leg after he was bitten by a shark off the coast of New York gave scientists the chance to test a new tactic: using DNA evidence to identify the species involved.

University of Florida researchers extracted a DNA sample from the tooth and compared it against a genetic dataset of common shark species to determine that a sand tiger shark was responsible for the bite.

This is the first time that a shark involved in a bite has been successfully identified using DNA, said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

“We’re as close to 100 percent sure as we can get that this shark was a sand tiger,” he said.

The bite was one of a pair of unusual attacks that occurred just minutes and miles apart at Fire Island National Seashore in mid-July. A 12-year-old girl who was also bitten reported seeing a 3- to 4-foot orange-brown animal with a dorsal fin.

Naylor believes both bites were caused by juvenile sand tiger sharks following schools of baitfish inshore.

Reuters reported that the victims received emergency medical treatment for puncture wounds in their right legs, and both were expected to fully recover.

Naylor said sand tiger bites are uncommon, and no reported sand tiger bites have proven fatal.

“If they really wanted to nobble you, they could,” Naylor said. “Sand tigers can weigh 500 pounds and have very sharp teeth. They have the potential to do real damage to humans but don’t, which underscores the fact that these bites are accidental. Sharks are not hunting humans.”

Shark attacks in New York are rare, but as large schools of baitfish head inshore, predators often follow, increasing the chance that they may bump into people swimming and playing in the water.

Naylor said that in the conditions at Fire Island – turbulent surf, high light, schooling baitfish – the sharks could easily have mistaken a solid object in the water, such as a human leg, for the fish they were pursuing. Unlike many shark species, sand tigers will feed during the day, he said, but they do not typically hunt when the surf is up, making the Fire Island bites exceptional.

“Perhaps incorrectly, I’m putting these in the bin of naïve young sharks,” he said. “I’m sure the children who were bitten were petrified, but the sharks probably were, too.”

According to the International Shark Attack File based at the Florida Museum, the last reported sand tiger bites near New York occurred in 1988 and 1974. The most recent attacks in the area involved unidentified species in 2017 and 2015.

About 70 percent of shark bites are caused by unidentified species, Naylor said. Great whites, tiger sharks and bull sharks are often blamed for attacks because of their large size and the fact that they are responsible for the majority of identifiable bites, but “maybe there are other species that are hard to identify or are not so conspicuous,” he said. “They could be hiding under the radar.”

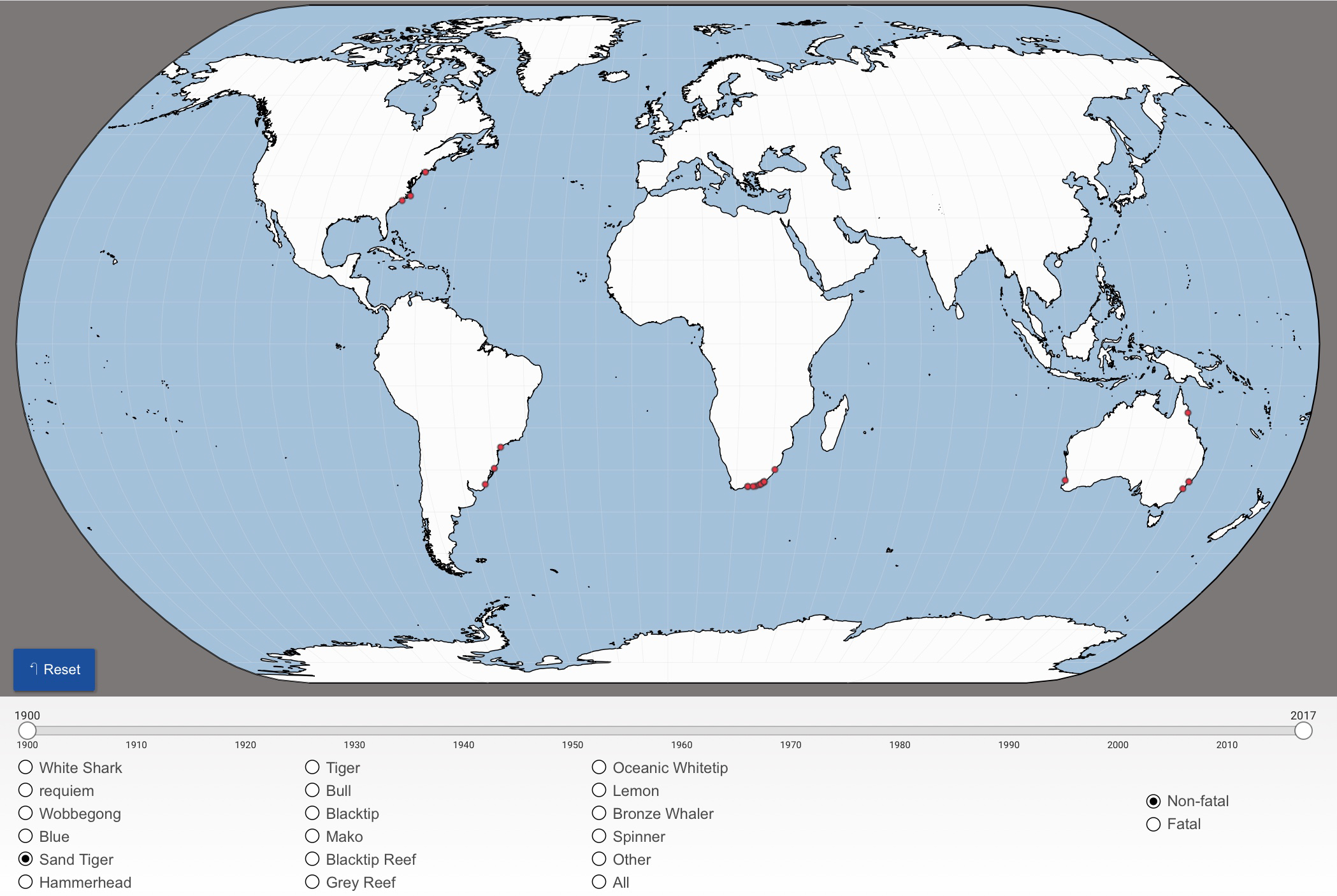

Map produced by Florida Program for Shark Research

Using DNA evidence could help pin some species names on these anonymous bites.

“People have talked about getting DNA out of teeth left behind in a bite, and we thought we’d go ahead and do it,” he said. “We didn’t know if it would work, but it did.”

Lindsay French, program manager for the FPSR, arranged for the tooth fragment to be sent down from New York. Postdoctoral researchers Lei Yang and Shannon Corrigan cleaned it of any possible contamination and swabbed for DNA inside the pulp cavity. After extracting the DNA and removing unwanted cellular debris, they broke the purified DNA into small pieces and put molecular “bookends” on either side of each piece of the fragmented DNA, creating a genomic “library.” The team could then select any particular “page” or set of pages from the library using a process called target capture.

“We chose to target a set of genes that we routinely use to identify different species of sharks,” Naylor said. “We determined their sequences and lined them up against a reference dataset that we maintain and found the sequences to have nearly a 100 percent match to sand tiger DNA.”

He said the FPSR is well equipped for this kind of genetic sleuthing, and the team would gladly analyze other DNA samples from bites.

In the meantime, beachgoers should exercise caution, not fear, when enjoying the water, Naylor said.

“It behooves us to be informed and understand these animals and take the appropriate precautions,” he said. “If baitfish are near shore, don’t go in. If people are fishing nearby or visibility is low, don’t go in. We share the ocean. I think it’s a good sign that there’s a lot of life in it.”

The research team published its findings in Nature Correspondence.

Data will be available in GenBank via the accession number MH823675.

Source: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1954

Learn more about the Florida Program for Shark Research at the Florida Museum.

Explore interactive maps of unprovoked shark attacks worldwide by shark species and year.