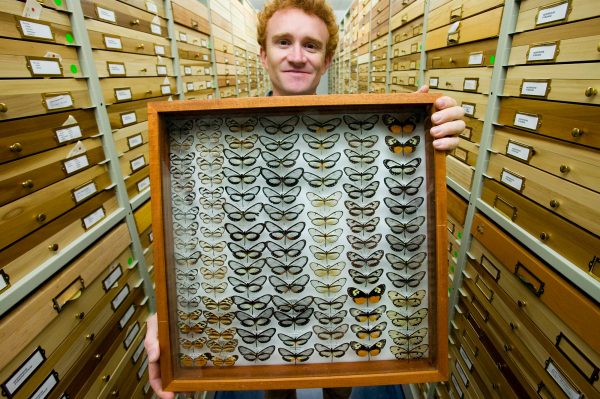

Photos by Keith Willmott | Illustration by Kristen Grace

About 150 years ago, Henry Walter Bates described mimicry based on his observations of adult butterflies in the Amazon, contributing key evidence supporting Darwin’s then novel theory of natural selection.

Recently, while conducting fieldwork in the lowlands of eastern Ecuador, Florida Museum of Natural History assistant curator of Lepidoptera Keith Willmott noticed another prime example of mimicry. Instead of looking up at the flyers, he found bright coloration in an earlier growth stage of butterflies — similar bright coloration in caterpillars was repeated in several unrelated species of ithomiine butterflies and again in a sawfly larva. Clad in blue and yellow with black tips, different species of the crawlers were not disguised as bird droppings or natural objects like many other caterpillars, and they were saying something different to their enemies: “Look out, we’re poisonous!”

Meanwhile, on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, fellow Florida Museum lepidopterist Andrei Sourakov was documenting another curious example of different caterpillar species with similar, conspicuous color patterns. A banded black, white and yellow pattern appeared in several species of danaine caterpillars, which include the monarch butterfly and its relatives.

Together, the researchers, who work in the Florida Museum’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, documented some of the most extensive examples of mimicry in caterpillars, in which different species mimic others as a defense against predators.

“Previous papers discussing mimicry mostly discuss a single, isolated case, typically involving a pair of species, but this is not just one pair, there are several species involved,” said Andre Victor Lucci Freitas, a professor in the Instituto de Biologia at Universidade Estadual de Campinas, who is familiar with the study. “There are lots of papers discussing mimicry in adult insects, but there are very few exploring mimicry of immature stages, like the caterpillar.”

The study in the November 2011 issue of The Annals of the Entomological Society of America helps scientists better understand how organisms depend upon one another, an important factor in predicting how disturbance of natural habitats may lead to species extinctions and loss of biodiversity.

“Mimicry in general is one of the best and earliest-studied examples of natural selection, and it can help us learn where evolutionary adaptations come from,” said Willmott, lead author of the study.

Based on the number of eggs laid by a single female butterfly, scientists estimate about 99 percent of caterpillars die before reaching the pupal stage. Survival tactics include sharp spines, toxic chemicals and hairs accompanied by bright warning coloration.

Photo by Eric Zamora

“It’s very interesting how caterpillars can detoxify a plant’s poisonous chemicals and resynthesize them for their own chemical defense or for pheromones,” said Florida Museum collection coordinator and study co-author Sourakov. “We can look at the caterpillars’ metabolic systems to understand how they deal with secondary plant compounds, the toxic plant substances used by mankind for centuries as tonics, spices, medicine and recreational drugs and poisons.”

Unlike camouflage, in which insects protect themselves by looking like inanimate or inedible objects, mimicry involves one species evolving similar warning color patterns to another.

“Caterpillars potentially have a lot of different selective pressures and I think understanding caterpillar mimicry can give insights into mimicry in general, which is common in many groups of animals,” Willmott said. “It’s is quite a mystery why we don’t see mimicry very often in caterpillars.”

The study focuses on the Neotropical Danaini, commonly known as milkweed butterflies, of the Caribbean Island of Hispaniola and Ithomiini, known as glasswing butterflies, that feed on plants in the tomato family of the upper Amazon in eastern Ecuador. Sourakov raised and observed danaine caterpillars, species that apparently form Müllerian mimicry rings, in which toxic species adopt the same warning color patterns so a predator will more quickly learn to avoid all of them.

In Ecuador, Willmott and study co-author Marianne Elias, from the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, found that 22 of 41 ithomine caterpillars displayed some kind of warning coloration. Five exhibited a previously undocumented pattern with a bright yellow body and blue tips, and four were likely Batesian mimics, in which edible species adopt the coloration of an unpalatable model species for protection. These “freeloaders” only appear to have the defense mechanisms of the model species.

“They act almost like parasites, because the mimics are actually edible and therefore deceive predators without having to invest in costly resources to maintain toxicity,” Willmott said. “Such a system can only be stable when the mimics are relatively rare, otherwise predators will learn the trick and attack more individuals of both mimics and models, driving models to evolve novel color patterns to escape the predators.”

Mimicry may be relatively rare in caterpillars because it is more difficult for them to establish bright coloration, and a brightly colored caterpillar has less chance of evading predators than a mobile adult butterfly, Willmott said.

Photo by Jeff Gage

“In adults, bright coloration may be favored by sexual selection for signaling to males and females,” Willmott said. “Bright colors may be disadvantageous since they attract predators, but advantageous for attracting mates. Once established, bright colors might then be modified by natural selection for mimicry, another possible reason why mimicry seems to evolve much more frequently in adults than in caterpillars.”

However, Sourakov believes mimicry is more common in caterpillars than scientists realize, but may receive less attention because larvae must be raised to adulthood to identify mimicry complexes, a process that takes weeks of lab work. Also, few collections of immature stages are maintained, and colors are not as well preserved in caterpillars.

“We know mimicry is an important ecological process for several species of animals, and I hope this study will give people the incentive to pursue further research into the immature stages of insects,” said Lucci Freitas. “We need to remember that in most insects, the immature stages are the most abundant in the environment.”

The researchers encourage people to raise butterflies and moths and post pictures of their caterpillars online so that more may be learned about their mimicry complexes.

“I think the focus is too much on adults and too little on caterpillars, so I’m looking out for the little guys,” Sourakov said.

Learn more about the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera & Biodiversity at the Florida Museum.