It’s a mammoth job, setting out to document all the butterflies of South America’s tropical Andean cordillera — a 3,000-mile swath of the planet crenulated into deep folds and gorges draped with cloud forests, grasslands, streams and waterfalls. But Florida Museum of Natural History butterfly researcher Keith Willmott and his colleagues are relishing the task.

Photo by Eric Zamora

Keith Willmott, an assistant curator of Lepidoptera at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the Florida Museum, began studying the butterflies of Ecuador with Smithsonian colleague, Jason Hall, in 1993. Now, he is spearheading the creation of a gigantic database for nearly 2,000 “true” butterfly species in the five tropical Andean countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. It’s the beginning of a systematic effort to fill the massive knowledge gap of Andean butterflies.

“People don’t understand what a complete vacuum of information there is at the moment for butterflies of the Andes, and the information that does exist is scattered and frequently unreliable,” Willmott said.

Nearly 5,500 butterfly species exist in the tropical Andean countries—and approximately 2,000 of these are in the families Papilionidae, Pieridae and Nymphalidae. Part of the “true” butterflies, these families are Willmott’s specialty, and the focus of the Tropical Andean Butterfly Diversity Project. This international project is establishing a foundation for Andean butterfly research by amassing a database stitched together from existing public and private collections, mainly from the U.S., U.K. and the five tropical Andean countries.

Photos by Eric Zamora

Scientists estimate that nearly one third of the world’s butterfly species are found in the tropical Andes, and of these almost half are geographically restricted to the mountainous cordillera—yet a lepidopterist traveling to this area to study butterfly diversity will encounter a shocking lack of published data. There are no reliable species lists, for example, nor are there comprehensive butterfly guides to help with identification, or scientific range maps detailing where even the most common Andean butterflies may be found.

“It is very difficult for a butterfly researcher to identify worthwhile projects in the Andes right now, because of the lack of baseline data,” Willmott said. “Information just doesn’t exist here.”

Before a butterfly researcher can work on conservation, he must know what exactly needs conserving.

“Ultimately, we’re hoping to make a first assessment of conservation status for each species using the World Conservation Union categories,” Willmott said. “Pretty much the only criterion we’re going to be able to use will be that of geographic range.”

The World Conservation Union, or IUCN, creates lists of species grouped by their extinction probability. One criterion used to partially assess the likelihood of extinction is range size. Many Andean butterfly species have extremely narrow home ranges, partly because the geography in this region is so variable and complex.

For example, some species only occur over the narrow, often 1-kilometer-wide ecotone between the paramo—a type of grassland usually found above the tree-line at over 3,000 meters in elevation—and the cloud forest below it. If that area is disturbed or cleared for agriculture, scientists are not likely to find the species they were seeking.

“Ultimately, we see the data gathered in this project as telling us not so much what we know, as what we don’t know about tropical Andean butterflies,” Willmott said. “We hope to identify not only areas that are priorities for conservation, but also regions and groups of butterflies that are in greatest need of study. Armed with this information, future researchers will be able to direct their energy toward filling in the many gaps in our knowledge of the world’s most biologically diverse butterfly fauna.”

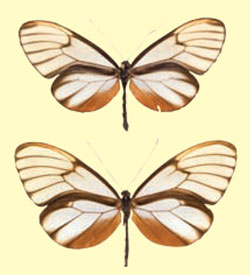

Andean Glasswing Butterflies

Florida Museum lepidopterist Keith Willmott is particularly fascinated with ithomiines, a characteristic group of Andean butterflies dubbed “glasswings” because many species have large, clear, translucent wing areas between dark orange and brown color splotches. Species within this subfamily, the Ithomiinae, have evolved an intricate and versatile anti-predator tactic.

“Interestingly, the adults are involved in mimicry of the wing color patterns that warn predators they are unpalatable,” Willmott said.

About 50 different “warning” color patterns are expressed among the 360 or so species in the subfamily Ithomiinae, and many species mimic each other. Ithomiines developed these warning color patterns to let would-be predators know they have an unsavory taste. Rather unusually, most ithomiine butterflies seem not to inherit their unsavory taste from the caterpillar stage, but acquire it as adults. Adult males feed on asters and other plants and ingest a certain chemical compound. Not only does it make them taste bad, it also is used to make a sex pheromone, that males disperse through specialized hair-like scales on their hindwings, to attract females. It’s thought that males then pass the anti-predation chemical to females during mating.

But other species of butterflies display warning colors even though they are not toxic.These color-mimicking butterflies enjoy the benefits of being avoided by predators, even though they themselves may make a tasty morsel for a hungry bird.

While the research on ithomiine ecology and evolution is an offshoot of Willmott’s other work in the Andes, it’s one example of how establishing a cohesive Andean butterfly database can add value to numerous other research fields.