Freshwater fishes in Florida are getting a close-up 60 years in the making.

Florida Museum of Natural History ichthyologists have written a new book, “Fishes in the Fresh Waters of Florida,” to describe the freshwater and saltwater species found in Florida’s lakes, rivers and streams.

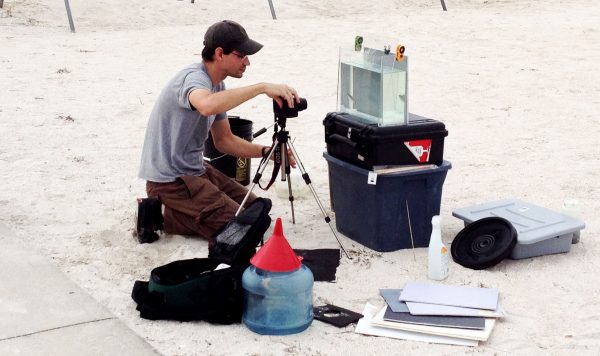

Florida Museum photo by Zachary Randall

The book, to be published by the University Press of Florida in fall 2017, is decades overdue, said coauthor Robert Robins, Florida Museum ichthyology collections manager. Other coauthors include Florida Museum scientists Larry Page, Jim Williams, Griffin Sheehy and Zachary Randall.

“The last comprehensive book on the topic was Archie Carr and Coleman Goin’s ‘Guide to the reptiles, amphibians, and fresh-water fishes of Florida,’ from 1955,” Robins said. “The book was good for its day, but it’s tremendously out of date.”

In the new book, researchers studied fish specimens from 10 museums and used more than 65,000 historic records to provide ranges for each species. These will be shown throughout the book in detailed maps created by Sheehy, a Florida Museum ichthyologist.

Photographs of the fish and the sites where they can be found will also be included so the book functions as an atlas and identification guide.

“There’s already a lot of scientists doing work on the fishes in the freshwaters of Florida,” Robins said. “We hope this guide makes it easier for them to identify the fishes they’re working with.”

The researchers reviewed specimens dating back to the early 20th century and others collected just last year. Robins said he noticed changes in Florida’s water systems are affecting where fish live.

For example, researchers had a difficult time trying to locate a Red-eyed Chub, a species commonly found throughout North Florida’s springs and lakes.

“There’s an ongoing need to sample the state and see what changes happened and how we can tie that to kind of an overall sustainable environment for both people and the natural world,” he said.

Robins said one of the benefits of studying museum specimens is that they have detailed data that anyone can review.

“If someone looks in our book and says, ‘I really doubt this animal occurs where they say it does,’ and it’s based upon these records, they can test whether or not we had it correctly identified,” he said. “And we want that. That’s how science moves forward – through revision.”

Rather than taking images of museum specimens previously collected and now preserved in alcohol, the research team traveled throughout Florida to photograph fishes in the wild.

The book includes multiple photos of some species to show different life stages or physical differences between males and females. Robins said the photos contribute greatly to the book’s accessibility to scientists, fishermen and others who will be impressed by the beauty of many of the specimens.

“I don’t think I can overstate the value of the photos,” Robins said. “One of the downsides of preserving specimens in alcohol is that much of the color they have in life is lost. You have to go out into the field and catch them. Without good color photographs of these fishes and life history stages, you don’t have as good of a chance of identifying the animal that you have at hand when you’re out in the field.”

Florida Museum photo by Rob Robins

Randall, a Florida Museum ichthyology research technician, photographed 205 of the 222 species described in the book. He photographs live fish using a clear water tank with a moveable pane to accommodate different size species.

He said although it is common practice to photograph fish in a tank, many do not use live specimens.

“A lot of times, people will image the fish after they are euthanized and pin up their fins,” Randall said. “An issue with that a lot of times is that they’re dead, so they look dead.”

He explained researchers try and find an individual fish that is representative for that species, including typical coloring and average length.

“Shooting them in the field is a pretty tedious process because they are moving around in the tank,” Randall said. “It just takes a lot of time to position them in the tanks so we get them as natural as they can be.”

Sometimes the scientists improvised to get the best images possible.

Randall described a time researchers were collecting images at the mouth of the Suwannee River, but had to set up their photo station on the boat because there was no suitable land nearby.

Florida Museum photo by Rob Robins

“For the photography setup, I am usually on my knees and photographing a tank that’s on some sort of box,” Randall said. “And in this particular case, the boxes were floating because the boat was rocking, so that was really difficult.”

He said Robins tried holding the box still, but they eventually moved the setup to a railing on the side of the boat, which helped make the process easier.

“That was definitely one of those moments we were happy with the results of the images. It was very difficult to photograph them and get them under the circumstances,” Randall said. “It was a lot of fun, for sure.”

On uniform dark gray backgrounds, the fish never give any indication they were taken out of from the water and placed in a tank to be photographed. But their physical properties will be useful to anyone interested in fish, Robins said.

“Besides use by scientists, we hope the book will be of great utility for fishing in the state of Florida, for students of ichthyology or just anybody with an interest in fishes, which is a pretty big group of folks,” he said. “Fishing is a huge economic driver for the state, and it interests a lot of residents and tourists alike.”

Learn more about the Ichthyology Collection at the Florida Museum.