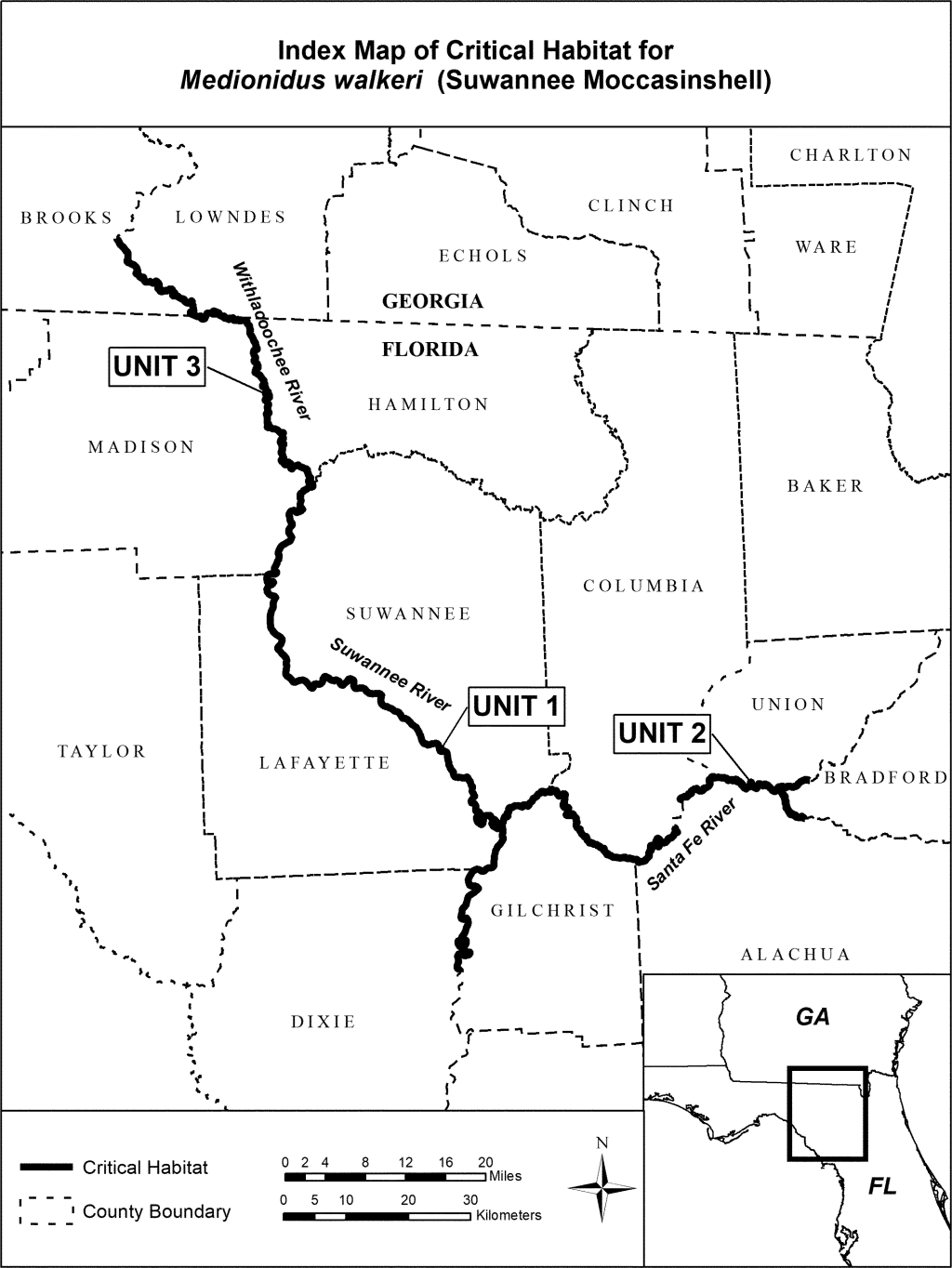

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has designated 190 miles of streams and rivers in Florida and Georgia as critical habitat for a rare species of freshwater mussel once thought to be extinct. The new ruling, which went into effect Aug. 2, outlines protective measures for the Suwannee moccasinshell, Medionidus walkeri, whose numbers have been steadily dwindling over the past several decades.

To determine the extent of this decline, biologists with the Florida Museum of Natural History, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Georgia Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Geological Survey pored over museum specimen data to establish how widespread the species had once been.

“Museum data is critical in providing the historical context of where these things are and how abundant they were. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have a clue as to what’s out there,” said Jim Williams, a research associate at the Florida Museum who helped with the study. Williams and his colleagues heavily relied on the Florida Museum’s invertebrate zoology collection, which houses over 400,000 mollusk specimens.

The designation of critical habitat means that any federal agency – or state agency using federal funds – needs to comply with a set of standards when working in and around the mussel environments.

Image courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Many ‘kidneys of the river’ are endangered

Freshwater mussels play an indispensable role as water purifiers in streams and rivers, filtering out organic debris and excess nutrients and providing a source of food for fish, turtles and a variety of mammals.

Although mussels can be found worldwide, North America boasts the highest diversity of freshwater mussels on Earth, with over 300 species that are mostly concentrated in the Southeast U.S.

Yet their diversity belies an extinction crisis that has been silently building over the past century. Freshwater mussels are considered among the most endangered animals in the U.S., with 70% of species at risk of extinction due to the long-term effects of pollution and development.

The Suwannee moccasinshell is listed as federally threatened under the Endangered Species Act and considered endangered in Georgia. Based on the reconstruction of its former range from museum collections and sightings, the species was once common throughout the Suwannee River Basin, a large watershed with multiple rivers and tributaries that straddles the border between Florida and Georgia. But as with many other freshwater mussels in the region, its numbers declined throughout much of the 20th century.

Biologists were unable to locate even a single individual between 1994 and 2008, despite spending countless hours searching streambeds and river channels, prompting fears the Suwannee moccasinshell had gone extinct.

“They’re not very easy to find, and if you see more than three individuals per site, you get really excited,” Williams said.

Looking for mussels in the Suwannee can be an especially time-consuming task because many of them burrow into the river’s sandy bottom. To find them, biologists have to slowly sift through sediment by hand.

“We call it grubbing,” said Sandy Pursifull, an ecologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who led the investigation into the status of Suwannee moccasinshells. “You go along the stream bottom and try to get a few inches down. Fortunately, the Suwannee River is mostly sand substrate, so you can really feel when you get the mussel.”

Suwannee moccasinshells might not look like much to a casual observer, but to mussel enthusiasts, there are several features that set them apart. Their oval, dark ochre shell gives them a passing resemblance to a moccasin, and a set of deeply furrowed grooves along one end make them particularly easy to distinguish. “Once you get good at it, you can identify them just by feel,” Pursifull said.

Photo courtesy of Michael Gangloff

Pursifull and biologists from the Florida Museum, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and Georgia Department of Natural Resources conducted aquatic surveys in 2014 and 2015. They looked extensively in places where museum specimens had been collected previously and in habitats where the species could occur.

After searching in over 140 sites, they came up nearly empty-handed.

In Florida, researchers were unable to find any Suwannee moccasinshells in many regions where they’d formerly occurred, including the lower Suwannee River and the upper reaches of the Santa Fe. They were also absent in the Withlacoochee River, meaning they may have entirely disappeared from Georgia, in total marking a 67% decline in their former range.

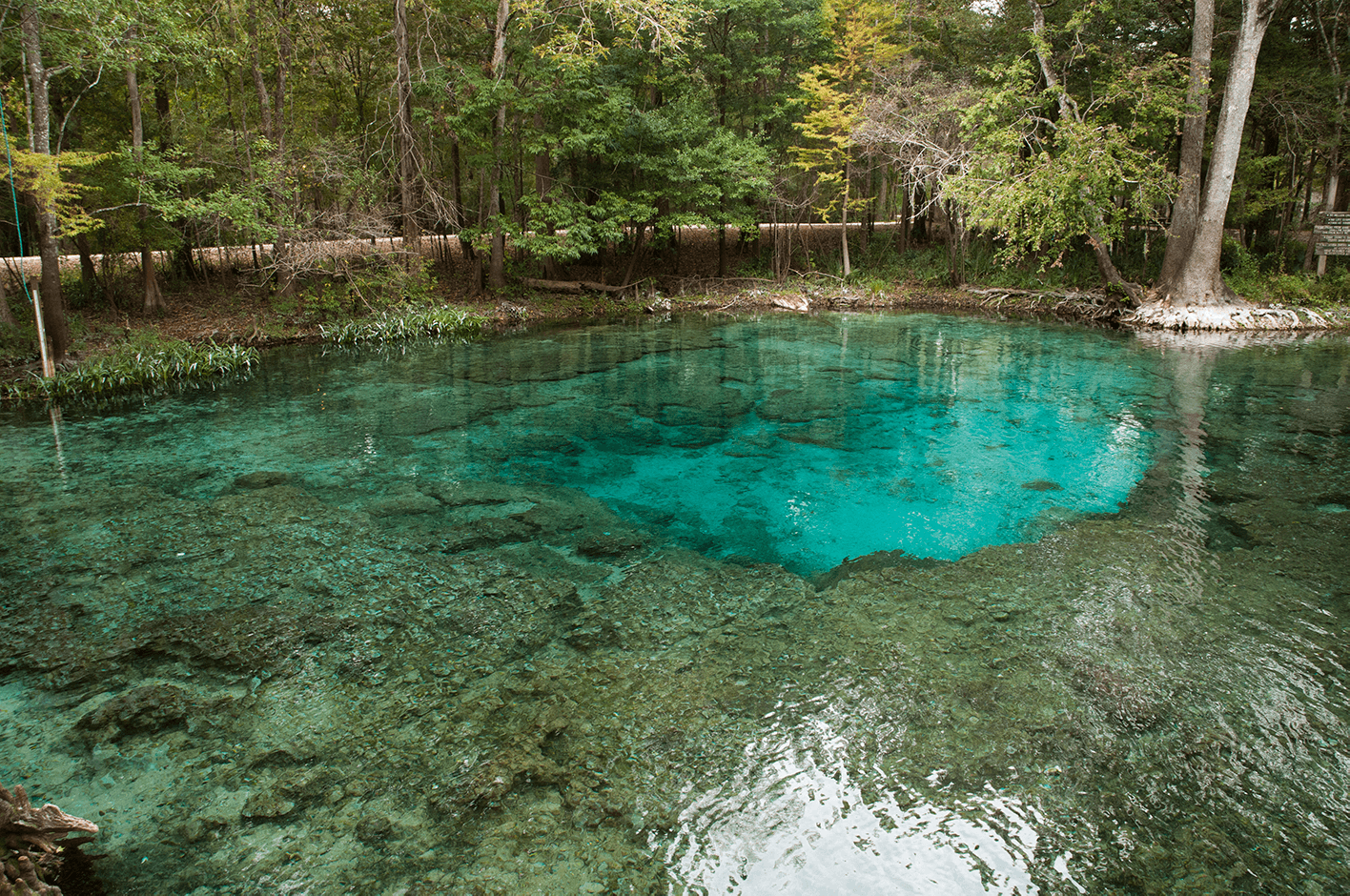

They’re now primarily restricted to a small stretch of the Suwannee River, where a network of springs helps regulate water temperature and dilute pollutants. Yet even here, state and federal biologists could only dredge up 73 individuals thinly spread across 75 miles of streambed.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

Freshwater mussels threatened by pollution, environmental change

The decline of freshwater mussels is due to several interconnected causes. Their role as water purifiers makes them extremely sensitive to pollution. Sewage spills from treatment plants are a common occurrence in the lower Withlacoochee, for example, where almost no moccasinshells remain. The spills can release millions of gallons of raw waste, which has a cascade of negative effects on the environment. The ammonia in human waste is particularly toxic to aquatic fish, mussels and other invertebrate life, Williams said.

Excess nutrients from nearby agricultural fields can also spark algal blooms that can smother and asphyxiate mussels. Even if a field isn’t directly adjacent to a river, overfertilization can cause nutrients to leach into the water table and ultimately make their way up through freshwater springs.

“The Suwannee Basin has a problem with fertilizers coming in, probably more so through the springs than anything, because the geology of that area is like Swiss cheese,” Pursifull said.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

These hazards are compounded by the complex life cycle of freshwater mussels. Adult mussels are sedentary, meaning they’re stuck in one place without the benefit of being able to pick up and move if their habitat is disturbed or polluted. The only time mussels move up or downstream is during their larval stage, in which they rely on fish as their means of transportation.

When a pregnant female is ready to release her larvae, she signals to unsuspecting fish nearby with an intricate lure disguised as food.

“There’s all sorts of mimicry,” Williams said. “Some of them mimic fish, and other invertebrates like snails or crayfish.” Any fish that moves in to investigate, hoping to find its next meal, is instead covered in larvae that latch onto its gills and hitch a ride to a new locale.

While some mussels are seemingly able to stow away on just about any fish that comes along, others are restricted to just one or two species. The Suwannee moccasinshell primarily relies on brown and blackbanded darters to get around, fish that don’t typically travel far. This likely inhibits the ability of these mussels to easily recover from rapid environmental degradation, Williams said.

Increased water runoff due to urbanization also reduces visibility in streams and rivers by adding suspended soils and kicking up sediment, making it harder for fish to find mussel lures. “If you have sediment in the water, and the water is cloudy, that means all the visual cues are gone,” Williams said.

Despite the odds, biologists remain hopeful that the protections conferred by the critical habitat designation may act as a catalyst in spurring conservation and population growth for the Suwannee moccasinshell.

“Agencies will now be required to consult with us to ensure that their project does not adversely modify or destroy critical habitat,” Pursifull said.

Any project that receives federal funding or permits is subject to the rule. In and around rivers, these most often include the construction of new bridges and landscape renovation carried out by state departments of transportation and dredge and fill permits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Sources: Jim Williams, fishwilliams@gmail.com;

Sandy Pursifull, Sandra_Pursifull@fws.gov

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452