Researchers, educators, students and the curious can explore the history of Florida’s Spanish missions via a new online database. Launched Wednesday, the Comparative Mission Archaeology Portal includes digitized artifacts, image galleries, personal narratives and details of excavation sites.

Under Spain’s rule, Florida was home to more than 100 Catholic missions, a network of outposts that served as the political, economic and religious backbone of the territory for nearly two centuries.

“Without the missions, St. Augustine and Spanish Florida could never have existed as long as they did,” said Gifford Waters, historical archaeology collection manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “They were truly some of the most important institutions in Spanish Florida from the 16th century to 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to the British. The missions provided critical supplies of food and labor for the Spanish colony. By bringing archaeological mission research online, our goal is to shine a light on a key part of Florida’s past.”

Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the database includes information from three North Florida sites: Baptizing Spring in Suwannee County, the site of the Mission San Juan de Guacara; Fig Springs in Columbia County, once home to the Mission San Martín de Timucua; and Fox Pond in Alachua County, the former site of the Mission San Francisco de Potano.

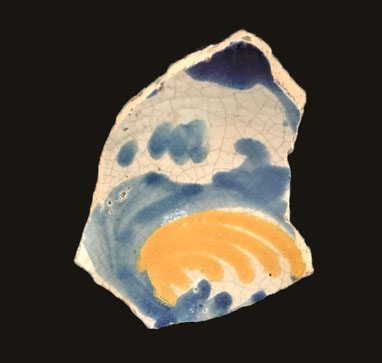

While the database has a research emphasis, it’s designed to be user-friendly to anyone looking for an introduction to what missions were like and common artifacts found during the excavations, such as pottery and projectile points, said Charles Cobb, the Florida Museum James E. Lockwood Jr., Professor of Historical Archaeology.

“There tend to be two narratives in the history of North American colonization, the English version and the Spanish,” Cobb said. “The English narrative tends to dominate, and CMAP helps right the balance. We often underappreciate the importance of the Spanish experience in the building of the American melting pot.”

Waters said CMAP will grow to include more of Florida’s missions, starting with Mission San Juan del Puerto, north of present-day Jacksonville, and St. Augustine’s Mission Nombre de Dios, to provide a more comprehensive look at the mission-dominated period of the state’s history. The long-term goal is to expand the database to encompass both Catholic and Protestant missions throughout the Americas.

“The next phase of the project is collaborating with other archaeologists and historians working on missions to build an even better and more comprehensive database, so we can truly do comparative research,” he said.

CMAP was developed in collaboration with the Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery at Monticello and designed by the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia.

Illuminating 200 years of Spanish presence in Florida

In Florida, the Jesuits began missionary work soon after the founding of St. Augustine in 1565, the capital of the territory, which spread across what is today the Southeastern U.S. But they were largely unsuccessful compared with the Franciscans, who took over their efforts in the 1570s.

Missions known as doctrinas were established in pre-existing native villages and usually consisted of a church, a convento, or friar’s residence, and a kitchen area. Friars would make daily trips to smaller outposts known as visitas, which consisted only of a church or chapel within the surrounding Native American village.

The aim of the missions was to convert indigenous people to Catholicism and provide labor and food to St. Augustine, which relied on a royal subsidy that was often late in coming “and likely would have failed if not for the support of the missions,” Waters said.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

While many Native American traditions remained unchanged under the mission system, indigenous people were subjected to forced labor, producing crops for the local mission and St. Augustine. In modern-day Gainesville and farther west into Tallahassee, the Spanish established cattle ranches, which often recruited Native American laborers from the missions. Missions were also avenues for introduced disease, which ravaged indigenous populations throughout Spanish Florida, Waters said.

The Spanish, who were vastly outnumbered by Native Americans, had learned from earlier colonizing efforts in the Caribbean and Central America to convert a chief first in order to subdue the rest of the village and to use the chief to mandate forced labor, Waters said.

But many friars were keenly aware of the fragility of their power and influence, Cobb said, and bent the rules handed down from St. Augustine to help ensure their own survival.

“Previous literature often cast friars and other religious leaders as handmaidens of the colonial project who were contributing to oppression and domination around the world,” he said. “But a growing trend is to look at what local accommodations were being made – friars knew they had to live with the local people. Looking at the historical context of specific missions is a really fascinating aspect.”

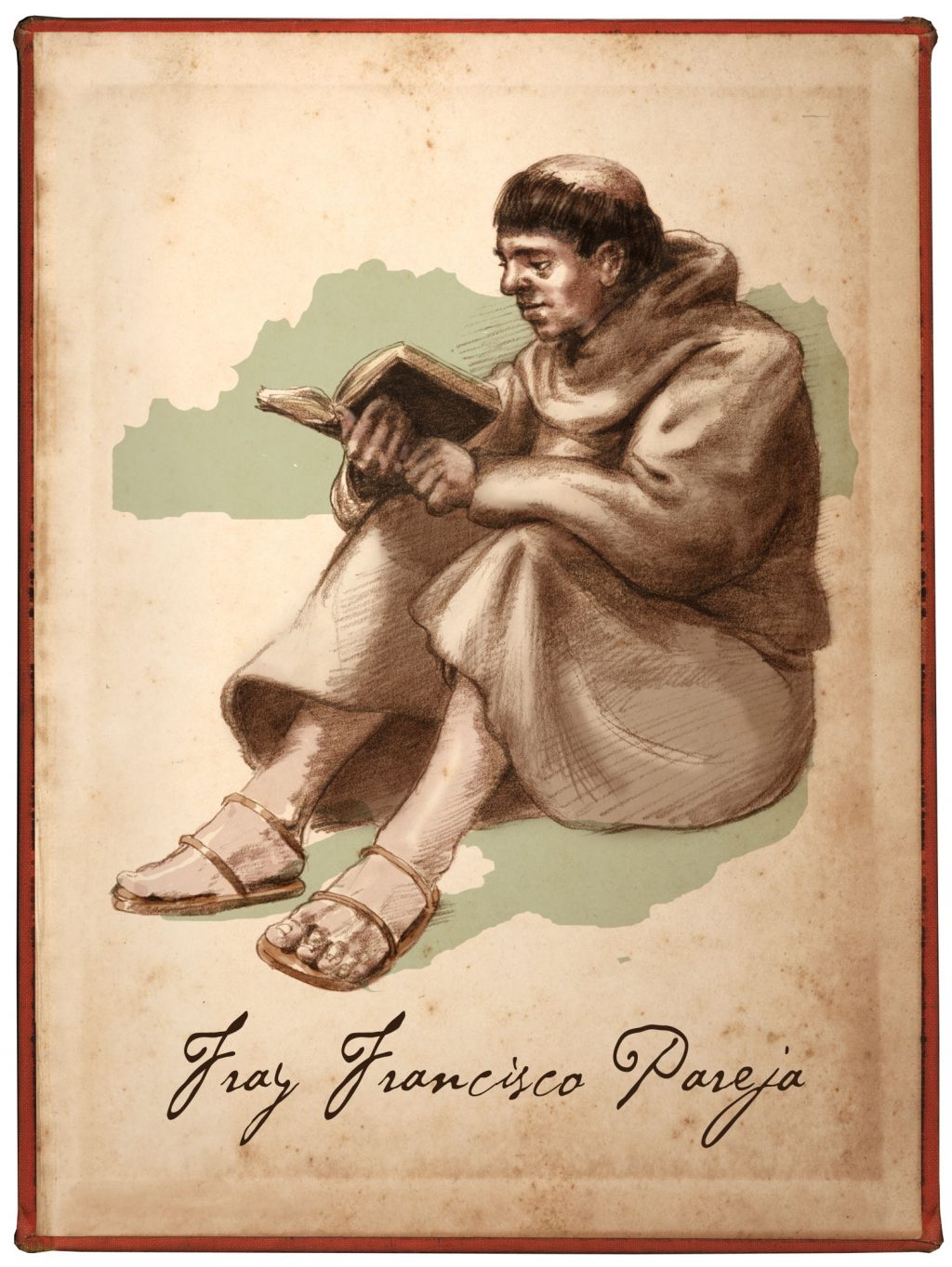

One such friar, whose story is told on CMAP, was Fray Francisco Pareja, who was assigned to San Juan del Puerto, a Timucua mission near present-day Jacksonville. Pareja learned the Timucua language and translated various religious texts into Timucuan. Emerging evidence also suggests that many texts previously attributed to friars may have been written by the Timucua themselves, Waters said.

Religious artifacts at mission sites are scarce and often limited to beads that may have been part of rosaries and religious medallions. Much of what researchers know about life at the missions comes from meticulous records kept by the Spanish.

The Florida Museum has played a prominent role in Spanish mission research since the 1950s and is a current leader internationally in collection digitization. CMAP is a natural synthesis of the two strengths, Cobb said.

“This yokes our historical archaeology program to the broader trends happening at the museum in terms of migrating collections online and making them available to everyone.”

Sources: Gifford Waters, gwaters@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1927;

Charles Cobb, ccobb@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-273-1916