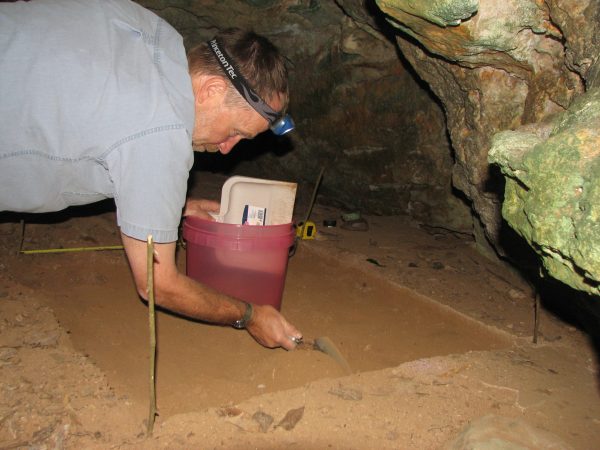

Photo courtesy of J. Angel Soto-Centeno

Sharing caves with millions of bats, the Caribbean’s first humans may have driven some species of the winged mammals to extinction.

“Scientists have been studying bat fossils in the Caribbean for years,” said David Steadman, curator of ornithology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. “The problem is, no one knew how old the fossils they were studying actually were.”

Bats have dominated the Caribbean for millennia, once sharing the islands with at least 73 species of mammals, such as primates, rodents and sloths. But following an ancient event called the Last Glacial Maximum, sea levels rose enormously, islands became smaller, and it is thought that most of the Caribbean’s land mammals became extinct.

New radiocarbon dates show that bats continued to thrive until around the time humans came to the islands, said Steadman, co-author of a new study appearing online in Scientific Reports in January 2015.

“Ours are the first radiocarbon dates for bat fossils in the whole West Indies,” Steadman said. “The new dates prove that certain bat populations were still in existence much later than previously thought — around the same time humans arrived.”

The study rejects previous research that directly connected climate change and the loss of land with the disappearance of bat populations. Steadman said knowing when and how Caribbean bats went extinct could contribute to better understanding biodiversity and how to save modern-day wildlife from meeting the same fate.

The new dates demonstrate that at least five species of bats withstood this climate change and reduced land area, only to be wiped out at a time when climate conditions were largely similar to those of today, said lead author J. Angel Soto-Centeno, a postdoctoral researcher at the American Museum of Natural History who began the research as a doctoral student studying mammalogy at the Florida Museum.

“Prehistoric and modern humans have had considerable impacts on island species and ecosystems, including the early Amerindians who settled in the Bahamas and altered the natural fire regimes on a large scale,” Soto-Centeno said. “We found that the demise of bat populations in the Bahamas coincides with similar land mammal, reptile and bird losses on other Caribbean islands.”

Researchers examined 2,000 bat fossils of 20 species from 20 fossil sites across the northern Caribbean and the Bahamas. One of these locations is a site called Ralph’s Cave, which was first described by Steadman, located on Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas.

Of the 97 fossil bats, mostly delicate wing bones, recovered from Ralph’s Cave, 51 represent species that still exist on Abaco. The study focuses on nine species of bats from four families known from the cave. The species Macrotus waterhousii was identified from 30 fossils and still lives in Ralph’s Cave. But before humans came to the island, it shared this roost with the five species that later disappeared from islands.

Florida Museum photo by J. Angel Soto-Centeno

Understanding why these bats went extinct while others like M. waterhousii continued to thrive could helps scientists predict which animals might adapt to changing environments, and which may face a similar fate to the extinct bats of Ralph’s Cave.

Twenty-five thousand years before people set foot on the pristine beaches of the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas, the world was a colder place. When the planet began to warm after glaciers covering much of the Earth melted and sea levels rose, large islands quickly became small islands.

Study researchers found that even when an island underwent a considerable reduction of land area, the minimum amount of suitable habitat to sustain healthy bat populations was likely unchanged. Steadman said the enduring result of the study is that extinction of bats in the Caribbean is much more complex than previously thought.

“Now that we have the technology to date these small bones, it opens up the possibility of determining the chronology of the extinction of bats in the Caribbean,” Steadman said. “We have good evidence that it is not the shrinking of islands that wiped out these populations, and the only thing we know happened in the last thousand years that might affect bat populations is the arrival of people.”

When humans arrived in the Bahamas, the horticulturists used fire to clear the forests and make room for farming. Steadman said this activity infringed on the natural habitats of the bats, which had already been significantly reduced after the Last Glacial Maximum.

“While we can’t reconstruct the details, we know people were using caves and starting fires in and around the caves,” Steadman said. “If you’re a bat that feeds on the nectar of a certain kind of flower, or the juice of a certain kind of fruit, you’re in trouble if your food source is being wiped out.”

Liliana Dávalos, assistant professor of conservation biology/ecology and evolution at the State University of New York at Stony Brook, said the new study is an important first step in understanding the potential changes in size of population that species of bats can undergo and still survive.

“We have never had such compelling evidence of persistence well after the end of the last glaciation,” Davalos said. “The study shows that populations thought to have gone extinct because of higher sea levels at the end of the last glaciation persisted well into the post-glacial.”

The study reveals the importance of directly dating the tiny, fragile bones of bats themselves rather than determining their age from other dated material found nearby. For example, a bat specimen from Haiti analyzed by study researchers proved to be much younger than a fossil of a sloth found in the same area whose age was known from previous dating.

In the future, Steadman said more testing could place the extinction of Caribbean bats at an even more recent date—further proving that humans were responsible for their demise.

“Two of the populations we examined are rare in the Bahamas,” he said. “The next step is to learn more about the bats’ ecology and life histories to learn why some species are more vulnerable than others.”