The Calusa may have been the only ancient people in North America who established a kingdom without practicing agriculture. Their sophistication and fierceness enabled them to resist Spanish domination for some 200 years.

The Calusa king Caalus, perched high on his throne in his grand house, watched as Pedro Menendez de Aviles, the first governor of La Florida, arrived with his entourage. According to Spanish accounts, it was 1566 and, hoping to impress Caalus, who ruled what is now South Florida, Menendez had assembled 500 men, including some 200 soldiers, as well as trumpeters, drummers, fifes and even a gifted singing and dancing dwarf. They arrived in seven vessels and climbed to the peak of Mound Key, a 30-foot-high, human-made island of shells and sand, to greet the king.

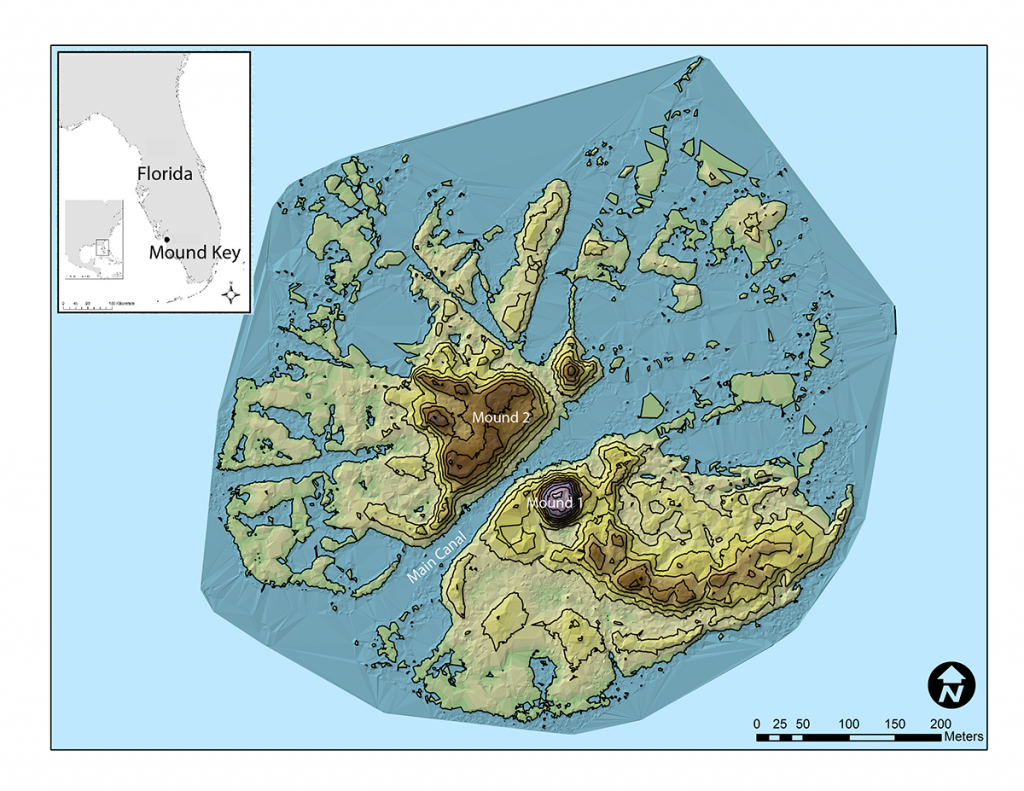

Mound Key was thought to be the seat of the powerful Calusa kingdom, and recent archaeological research there has confirmed it was in fact the capital and also revealed the extent of ancient landscape alteration, monumental construction and engineering ingenuity that allowed the Calusa’s population to grow to an estimated 20,000 without reliance on agriculture. Indeed, given the results of recent research, they are now considered one of the most politically complex groups of non-agriculturalists in the ancient world.

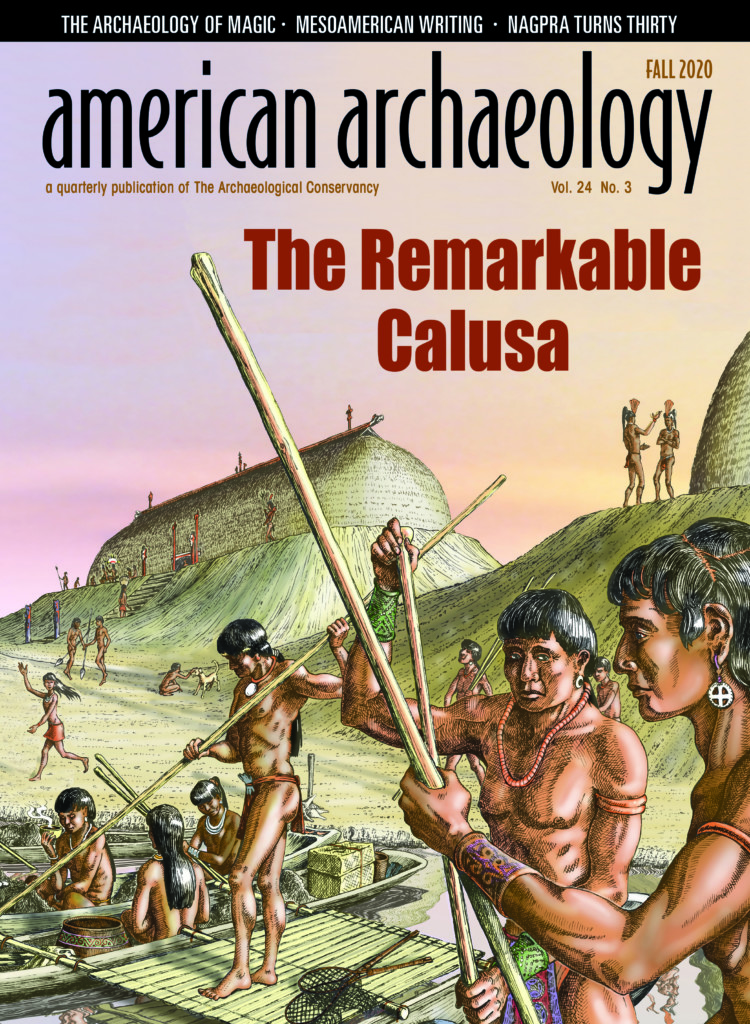

American Archaeology cover, featuring Florida Museum illustration by Merald Clark

“The Calusa have long fascinated archaeologists because they were a fisher-gatherer-hunter society that attained unusual social complexity,” said William Marquardt, curator emeritus of South Florida Archaeology and Ethnography at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Marquardt and Victor Thompson of the University of Georgia are co-directing research at Mound Key, which has a complex arrangement of shell midden mounds, canals, watercourts and other features.

“For me, the work has been absolutely fantastic and since we began it has been one discovery after another,” said Thompson.

After A.D. 1000, the Calusa began to grow in size and complexity, wielding their military might, trading widely and collecting tribute along those trade routes that extended for hundreds of miles. They built massive mounds of shells and sand, dug large canals, engineered sophisticated fish corrals, held elaborate ceremonies, created remarkable works of art, such as intricately carved wooden masks and traversed the waters in canoes made from hollowed-out logs. Known as the first shell collectors, the Calusa used shells as tools, utensils, building materials, vessels for domestic and ceremonial use and for personal adornment.

“For a long time, societies that relied on fishing, hunting and gathering were assumed to be less advanced,” said Marquardt. “But our work over the past 35 years has shown the Calusa developed a politically complex society with sophisticated architecture, religion, a military, specialists, long-distance trade and social ranking – all without being farmers.”

“The fact that the Calusa were fishers, not farmers, created tension between them and the Spaniards, who arrived in Florida when the Calusa kingdom was at its zenith,” Thompson said.

The Spanish were used to dealing with natives who farmed and who provided the Spanish with some of their food.

Marquardt, Thompson and other University of Georgia colleagues and students began fieldwork at Mound Key in 2013, funded by the National Geographic Society.

“We began with a basic set of questions,” said Marquardt. “Could we find unequivocal architectural evidence that Mound Key was the Calusa capital town, as had long been suggested? What formation processes resulted in the complex of mounds and other features there? And to what extent does the occupational and architectural history speak to broader issues of Calusa complexity? So, we needed information on large-scale architecture, the timing and tempo of shell midden mound formation and the timing of large-scale public architecture.”

Florida Museum illustration by Merald Clark

The first phase of work included the creation of a detailed topographic map of the island using LiDAR, which gave archaeologists information about its structures and geography. The team conducted a geophysical survey of both large mounds at the site, known as Mounds 1 and 2, and then they partially excavated the areas where ground-penetrating radar had indicated the locations of features and structures. They collected materials for accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating and sediment samples for archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological analysis. They also cored sediments on and off the island to help describe and date environmental changes during the site’s occupation. It was during this phase of research that the team located and documented the massive king’s house, showing it was indeed every bit as impressive as Spanish accounts, which claimed it was large enough to accommodate some 2,000 people.

“The architectural remains of the king’s house were relatively easy to find, but difficult to interpret at first,” Marquardt said. “Detailed analysis and AMS dates led us to the realization that the structure went through at least three phases of building activity over several centuries, the earliest phase dating to around A.D. 1000.”

The research team uncovered a network of post holes and foundation trenches that indicate a large structure measuring about 80 feet long and 65 feet wide covered the summit of the island’s highest hill. In a feat of organized labor that was also suggestive of their expansive trade network, the Calusa appear to have brought pine wood to the island from elsewhere in Florida to build the dwelling. It was during this time that the team located the Spanish fort – Fort San Antón de Carlos, named for the Catholic patron saint of lost things – that historic documents said was built near Caalus’ house in 1566.

According to the documents, the brushwood and lumber fort encompassed some 36 structures. Prior surface surveys had revealed Spanish ceramics, beads and other artifacts, but the location of the fort hadn’t been determined. They began preliminary investigations of the fort, which was located on Mound 2 and housed one of the first Jesuit missions established in the U.S.

The researchers used ground penetrating radar and LiDAR to locate and map the fort’s structures, which they then partially excavated. They recovered various types of Spanish artifacts such as majolica ceramics, hand-wrought nails and spikes, a bale seal and olive jar sherds, as well as native artifacts.

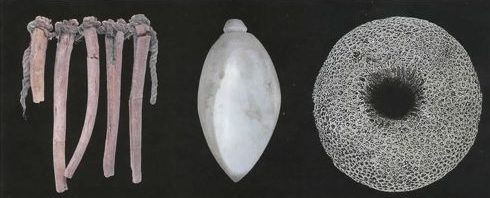

Florida Museum artifact photos by Jeff Gage. Image by Pat Payne for American Archaeology.

Radiocarbon dating of carbonized wood, a deer bone and a shell verified the fort’s mid-16th-century date. The archaeologists were surprised to discover the Spanish used a primitive shell concrete known as tabby to stabilize the wall posts of their wooden structures. Tabby was an Old World concrete consisting of lime from burned shells mixed with sand, ash, water and broken shells. Fort San Anton de Carlos is the first example of the use of tabby in North America.

“Tabby,” also called “tabbi” or “tapia,” is made by burning shells to create lime, which is then mixed with sand, ash, water and broken shells. At Mound Key, the Spaniards used primitive tabby as a mortar to stabilize the posts in the walls of their wooden structures. Tabby was later used by the English in their American colonies and in Southern plantations.

“Figuring out how to shore up the walls of wooden buildings using a very early kind of tabby architecture is impressive and represents creative thinking and ingenuity in an unfamiliar and challenging setting,” said Marquardt.

“The fort was obviously a massive presence on Mound Key, both in scale and as an example of European culture, but it appears that native food procurement, living arrangements and much of Calusa daily life continued with only minimal changes,” said archaeologist Traci Ardren of the University of Miami, who was not involved with the team’s work.

“At first, there must have been an uneasy tolerance of one another, as the Spanish built their fort,” Marquardt explained. “The Calusa king initially allied himself with Menendez, hoping to gain an advantage over his rivals elsewhere in the Florida peninsula.”

But the Spanish not only refused to fight Caalus’ rivals, they also wanted to convert his people to Catholicism, which eventually led to conflict between the Spanish and the Calusa. In 1569, just three years after the Spanish fort was built, the Calusa attacked a Spanish supply ship, prompting more violence. Historic documents say the Calusa then set fire to Mound Key and fled the island, which also prompted the Spanish to leave. By the early 1600s the Calusa returned to Mound Key and reestablished their capital. The Franciscans established a mission there in the late 17th century, but the Calusa evicted them after a few months’ time.

Archaeologists have long pondered how the Calusa could have grown to a population of some 20,000 and dominated such a vast region without relying on agriculture. It appears that the answer is their watercourts, which were discovered back in the 1890s. These massive, rectangular structures built of shell and sediment enclose large areas on both sides of the mouth of Mound Key’s great canal, a marine highway nearly 2,000 feet long and about 100 feet wide that bisects the island.

“Researchers have previously hypothesized the watercourts were designed to hold fish, but this was the first attempt to study the structures systematically, including when they were built and how that timing correlates with other Calusa construction projects,” Marquardt said.

Florida Museum illustration by Merald Clark

ln 2017, funded by the National Science Foundation, the research team began a systematic investigation of these structures, the largest of which is about 36,000 square feet, with a surrounding berm of shell and sediment that stood about three feet high. They determined that the enclosures, which were built on a foundation of oyster shells, walled off portions of the estuary, serving as traps and short-term holding pens for fish before they were eaten, smoked, or dried for later consumption. Openings in the berms likely allowed the Calusa to drive fish into the enclosures for short-term storage, and then they closed those openings with nets and wooden gates. Fish bones and scales recovered from one of the watercourts indicate the Calusa were capturing schooling species such as mullet, pinfish and herring.

“Engineering the courts required an intimate understanding of daily and seasonal tides, hydrology and the biology of various fish species,” said Thompson.

“The 2017 excavations were really exciting for a number of reasons,” Thompson said. “Excavation of the watercourts yielded artifacts like cordage that are not normally preserved at archaeological sites. Seeing the work of the Calusa in these materials first-hand were really exciting moments for us.”

The archaeologists recovered seeds, wood, palm-fiber cordage that likely came from Calusa fishing nets and even fish scales from the waterlogged levels. These deposits were carefully water-screened using a series of nested screens in order to capture even the finest organic materials.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

“We could not anticipate the extraordinary preservation of organic materials down below the water table,” Marquardt noted. “This now makes three southwest Florida sites with wet-site preservation of such items as wood, cordage and netting: the Pineland Site Complex, Key Marco and now Mound Key.”

Radiocarbon dating of organic materials associated with the watercourts indicates they were built between A.D. 1300 and 1400, toward the end of a second phase of construction on the king’s house. Fish stored in the watercourts likely fed the workers who built the massive palace. Around A.D. 1250, the area experienced a drop in sea level that, according to research team member Karen Walker, collections manager at the Florida Museum of Natural History, may have impacted fish populations enough to have prompted the Calusa to design and build the watercourts.

“The archaeology of the Calusa is important worldwide in that it illustrates the development of very pronounced hierarchy, inequality, monumentality and large-scale infrastructure by hunter-gatherer-fisher societies,” said Chris Rodning of Tulane University, who was not involved with this research.

The immensity of the king’s house, as well as the huge shell mounds and the canals required “large amounts of labor and mechanisms to mobilize and to organize that labor” that he thinks are indicative of a lower class that worked at the behest of the Calusa’s elites.

Such hierarchy and inequality are generally characteristics of societies that practice agriculture, he observed. “The Calusa case also illustrates remarkably sophisticated engagements with, and long-term large-scale management of, coastal and estuarine environments.”

The Calusa kingdom was eventually devastated by European diseases as well as slave raids by enemy tribes. Historical documents indicate that by the mid-1700s, the dwindling Calusa population had fled to Cuba, or the Florida Keys.

“The story of the Calusa during the Spanish occupation of La Florida is a complicated one,” said Thompson. “We do not fully understand the complexities of what happened to them. It is likely there are descendants of the Calusa living among the Native American people of Florida and in Cuba today.”

“In terms of Mound Key, much more can be learned about the Spanish fort and mission, the relations between the Calusa and the Spaniards and the earlier, pre-contact occupations of the island,” Marquardt said. “Honestly, we have explored a very small sample of Mound Key and other nearby island sites.”

“ln the next couple of years,” Thompson added, “I’d like to return to Mound Key to look more closely at the fort and its structures to really delve into Calusa-Spanish interactions.”

Tamara Jager Stewart is the assistant editor of “American Archaelogy” and the Conservancy’s Southwest region projects director. This article first appeared in the magazine’s fall 2020 issue.