In 2003, smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) had the unenviable distinction of being the first native marine fish listed under the Endangered Species Act. The classification followed decades of declining populations due to habitat loss, overharvesting and mortality as fisheries bycatch. Now, 20 years later, a 13-foot adult female captured off the coast of Cedar Key, FL suggests the species may be making a slow but spirited comeback.

The sawfish was caught, tagged and released June 6 during an annual shark field course co-taught by Dean Grubbs, the associate director of research at Florida State University’s Coastal and Marine Laboratory and a member of the U.S. Smalltooth Sawfish Recovery Implementation Team; and by Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s shark research program.

“This is the furthest north an individual has been tagged by the sawfish recovery team in the last 30 to 40 years,” Naylor said.

Sawfish are a type of elasmobranch, a group containing sharks, skates and rays, and they were once a common sight along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. They were historically most abundant near Florida but occasionally ranged from Texas to as far north as North Carolina. Females give birth to live young, which hunt and shelter among the protective, stiltlike roots of mangroves. But widescale coastal development along the coast has drastically decreased the number of mangrove forests, reducing the size and suitability of available environments for sawfish to use as nurseries.

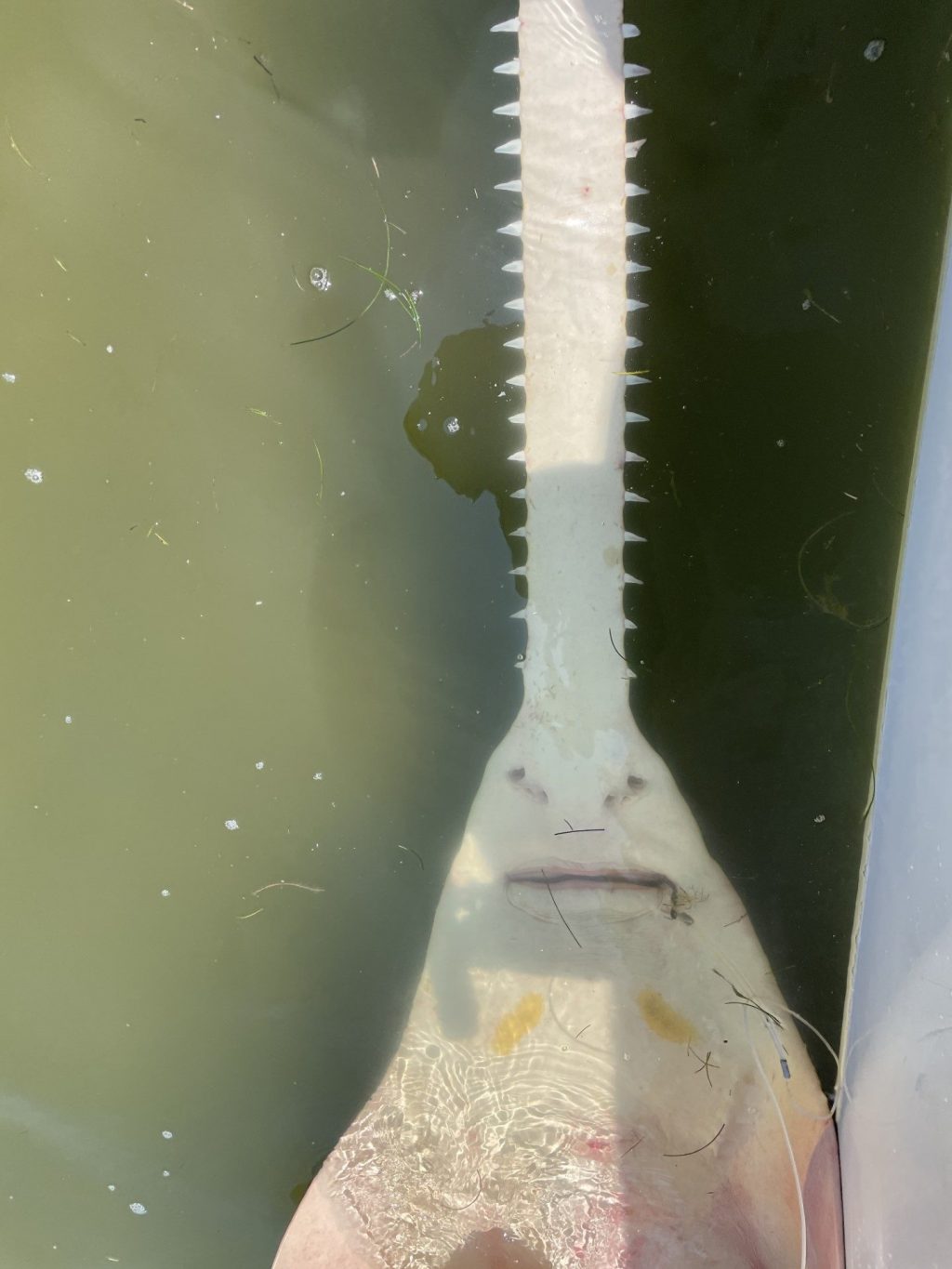

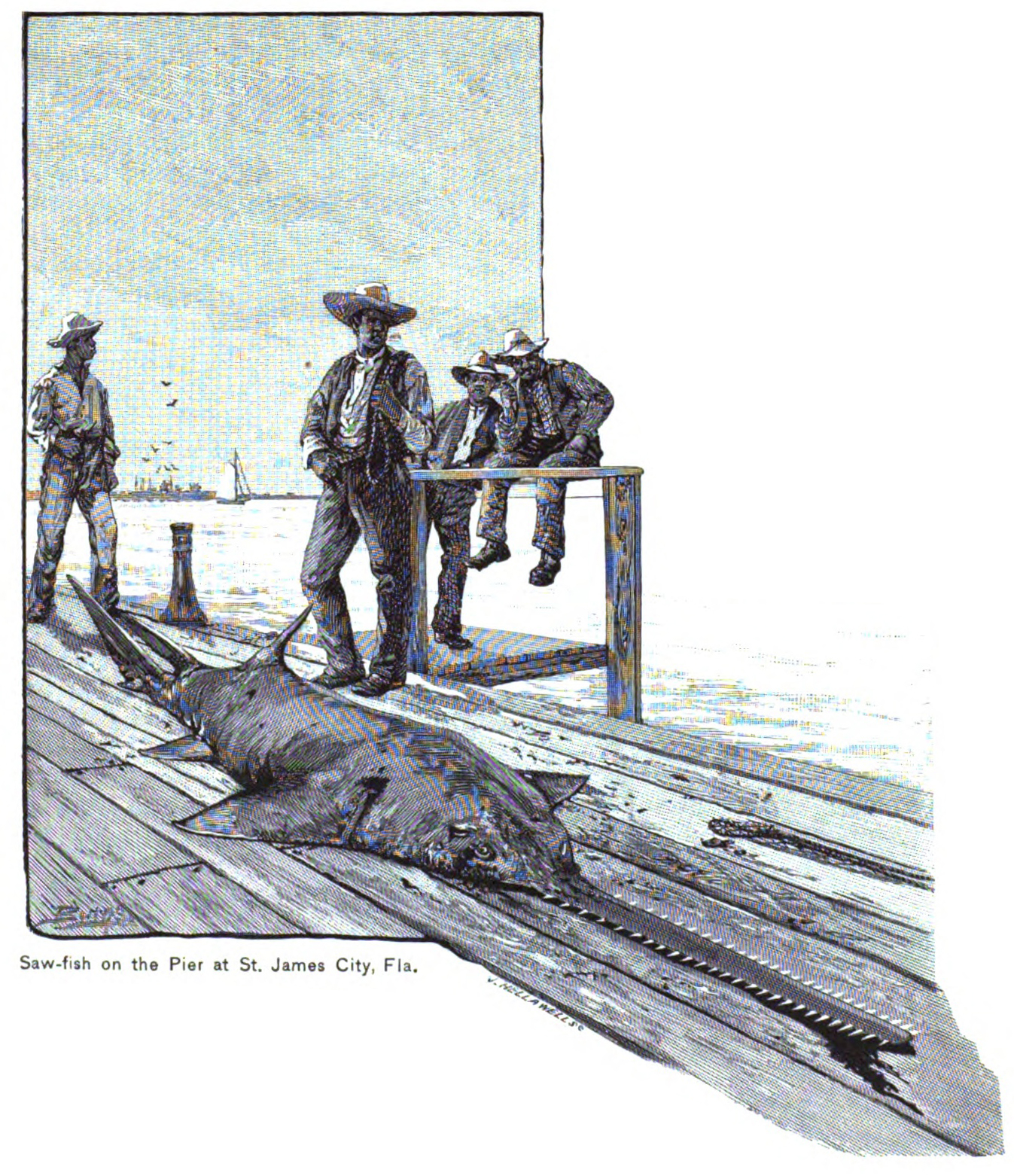

Their most conspicuous feature — a long, flat-edged blade studded with teeth — marked them as a prized possession among trophy hunters.

Image from Scribner's Magazine (1889), CC0

Early sensationalized accounts of their size and ferocity attracted thrill-seeking anglers, who collected and sold the saws, called rostrums, as curios. But the bigger threat to sawfish was from incidental bycatch. Their saws become easily entangled in gill and trawl nets, and freeing them poses the risk of injury to anyone attempting to remove the gear. As a result, many sawfish were either killed or released only after their saws had been severed, jeopardizing their ability to hunt.

Throughout the 20th century, smalltooth sawfish populations declined by more than 90%, and experts were dubious about their ability to quickly recover, even with the aid of protective regulations.

So when Naylor and Grubbs began reeling in their line, expecting to haul aboard a juvenile shark for the class to inspect, they were surprised to find they’d snagged a full-sized sawfish instead.

“I felt something heavy on the line, and my first thought was that it was likely a nurse shark,” said Grubbs.

Nurse sharks are large bottom feeders that share many of the same habitats as sawfish, but when the line jerked abruptly at a sharp angle, Grubbs knew he’d caught something much larger and more aggressive. “I was pretty sure this was a sawfish, but I remained stone-faced because I didn’t want to disappoint the students if I was wrong. I saw the tail before the rostrum, so I lost my calm at that point and screamed ‘Sawfish! It’s a sawfish!’”

Photo courtesy of Alex Tate

Quick on their feet, Grubbs and his graduate students carefully restrained the sawfish while another personnel member piloted a skiff back to shore to retrieve a tagging device, which no one had imagined they’d need. The tag will allow the team to track the animal’s movements for the next 10 years and is part of a broader effort by federal and state agencies, universities and non-governmental organizations to monitor sawfish populations.

A close inspection of the sawfish revealed it had mating scars on its fins and sides. There are few, if any, records of sawfish mating habits, but closely related rays and sharks exhibit courtship behavior in which the males bite the fins of their female partners before mating. Smalltooth sawfish have a lengthy lifecycle in which females give birth to a small litter of seven to 14 juveniles, which take several years to reach reproductive maturity. Their slow development has limited the recovery of sawtooth populations, but mating scars are a positive sign that their numbers are continuing to rebound.

“What’s remarkable to me is that they’re creeping back into exactly the previous habitats and range from which they’ve been extirpated,” Naylor said. “It’s as if they have a deeply embedded knowledge of where to go.”

The sawfish encounter occurred during the third edition of the shark course, jointly offered through the University of Florida and Florida State University. The course is a deeply immersive, two-week summer camp like no other, designed to intimately familiarize students with the sharks that inhabit the Gulf of Mexico. The gulf’s warm, nutrient-rich waters are a magnet for fish and — by extension — a variety of sharks and rays.

According to Naylor, the sawfish sighting taught a lesson that would otherwise have been impossible to convey. “I can’t think of a better way for a group of young people studying environmental and conservation biology to learn about this critically endangered and incredibly spectacular animal. So much of the news about Earth’s climate and environment is doom and gloom, but this is a potent reminder that if you leave things alone, many species are capable of recovery.”

Source: Gavin Naylor, gnaylor@flmnh.ufl.edu;

Dean Grubbs, dgrubbs2@fsu.edu

Writer: Jerald Pinson, jpinson@flmnh.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452