When lice attack, it’s hard to call it a blessing.

People have been tormented by the blood-sucking parasites for thousands of years, awaiting the latest technology to annihilate them. But some researchers are counting their lice and shipping them to genetics laboratories, where they are used to unlock clues about human history.

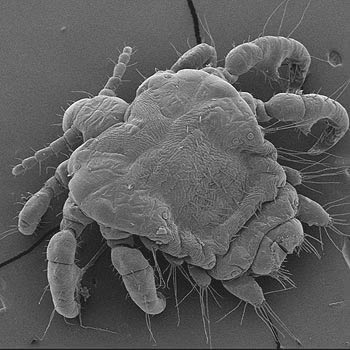

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

David Reed, associate curator of mammals at the Florida Museum of Natural History, studies lice in modern humans to better understand human evolution and migration patterns. His latest study used DNA sequencing to calculate when clothing lice first began to diverge genetically from human head lice.

“We wanted to find another method for pinpointing when humans might have first started wearing clothing,” Reed said. “Because they are so well adapted to clothing, we know that body lice or clothing lice almost certainly didn’t exist until clothing came about in humans.”

The results of the UF study show humans started wearing clothes about 170,000 years ago, a technology which allowed them to successfully migrate out of Africa.

Funded by the National Science Foundation, the study is available online and in the January 2011 print edition of Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Lice are studied because unlike most other parasites, they are stranded on lineages of hosts over long periods of evolutionary time. Host-parasite coevolution allows scientists to learn about evolutionary changes in the host based on evolutionary changes found in the parasite.

“We use these lice as a marker, if you will, as a marker of their host’s evolutionary history,” Reed said.

The data shows modern humans started wearing clothes about 70,000 years before they migrated into colder climates and higher latitudes, which began about 100,000 years ago. This date would be virtually impossible to determine using archaeological data because early clothing would not survive until the present in archaeological sites.

The results also show humans started wearing clothes well after they lost body hair, which genetic skin coloration research pinpoints at about 1 million years ago. This finding means humans spent a considerable amount of time without body hair and without clothing, Reed said.

“It’s just interesting to think that humans were able to survive in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years without clothing and without body hair, and that it wasn’t until they had clothing that modern humans were then moving out of Africa into other parts of the world,” Reed said.

Photo by Vincent S. Smith

A study of clothing lice in 2003 led by Mark Stoneking, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany, estimated humans first began wearing clothes about 107,000 years ago. But the UF research includes new data and calculation methods better suited for the question.

“The new result from this lice study is an unexpectedly early date for clothing, much older than the earliest solid archaeological evidence, but it makes sense,” said Ian Gilligan, lecturer in the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at The Australian National University. “It means modern humans probably started wearing clothes on a regular basis to keep warm when they were first exposed to Ice Age conditions.”

The last Ice Age occurred about 120,000 years ago, but the study’s date suggests humans started wearing clothes in the preceding Ice Age 180,000 years ago, according to temperature estimates from ice core studies, Gilligan said. Modern humans first appeared about 200,000 years ago.

Because archaic hominins did not leave descendants of clothing lice for sampling, the study does not explore the possibility archaic hominins outside of Africa were clothed in some fashion 800,000 years ago. But while archaic humans were able to survive for many generations outside Africa, only modern humans persisted there until the present.

“The things that may have made us much more successful in that endeavor hundreds of thousands of years later were technologies like the controlled use of fire, the ability to use clothing, new hunting strategies and new stone tools,” Reed said.

Direct anthropological evidence of clothing use has been limited to items such as eyed needles, which appeared 40,000 years ago, and scrapers from about 780,000 years ago suited for cleaning animal skins which could have been used as coverings. Because the date calculated in the study was earlier than evidence of tailored garments, the first clothing would have been simple, such as loose animal skins, Reed said.

Though simplistic, this clothing would have been like new real estate for lice.

“When new real estate opened up, new habitat became available, and it only makes sense that head louse populations would try and make use of that habitat,” Reed said. “And they were successful at it, that’s why we have clothing lice today.”

Because lice exist worldwide, much of the study’s success depended on contributions of specimens over the last few years from global locations, including homeless shelters and local health clinics.

The use of lice as a unique data set to apply to human evolution has only developed within the last 20 years, and it provides independent data that could be used in medicine, evolutionary biology, ecology or any number of fields, Reed said.

“It gives the opportunity to study host-switching and invading new hosts, which has everything to do with diseases that do the same thing, like emerging infectious diseases that affect humans,” Reed said.

Study co-authors were Melissa Toups, previously with UF and now at Indiana University, Andrew Kitchen, formerly with UF and presently at The Pennsylvania State University, and Jessica Light of Texas A&M University. The researchers completed the five-year project with the help of Reed’s NSF Faculty Early Career Development Award, which is granted to researchers who exemplify the teacher-researcher role.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, it’s interesting to learn about the evolutionary histories of a mammal and its parasite that are so intertwined, so interconnected over vast, long time scales,” Reed said. “They just generate such interesting evolutionary questions.”