Electric power companies dedicate significant resources to clearing overgrown plants and debris from the area surrounding power lines. These areas are known as electric rights-of-way, and anything that obstructs access to them can threaten power outages, hinder public safety and make it harder for utility crews to perform necessary maintenance and repairs.

A new paper shows that appropriate vegetation management is beneficial not only to utility companies but to pollinating insects as well. In the largest scale study of its kind, covering the greatest number of sites and species, researchers from the Florida Museum of Natural History surveyed 18 rights-of-way managed by Duke Energy. They found that sites being maintained on schedule, which kept woody vegetation to a minimum, had a greater quantity and diversity of flowering plants and pollinating insects.

“It’s a win-win,” said Chase Kimmel, insect conservation biologist at the museum and first author of the study. “It’s exciting that the goals of promoting pollinator habitats are in line with how Duke Energy would like to manage that land.”

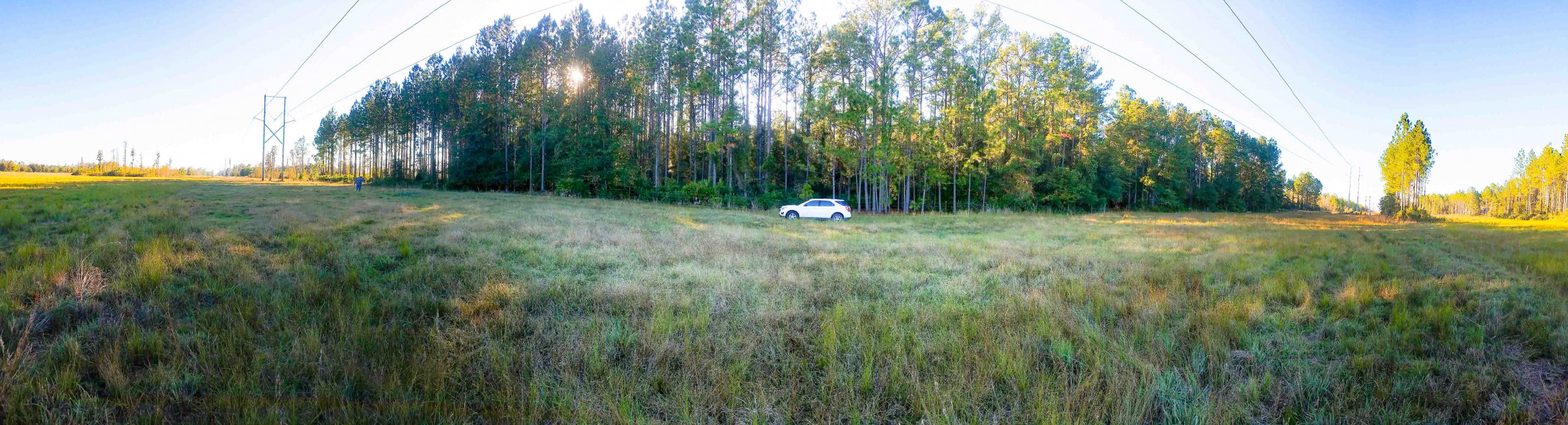

Photo courtesy of Jonathan Bremer

Many of Florida’s insect pollinators thrive in early successional habitats, which are created by occasional disturbances, such as fire. Historically, the Florida landscape was a patchwork of different habitat types. As fields grew into forests, the resulting wood provided kindling for fires that ignited naturally, often from lightning strikes. The blaze cleared the understory and opened the canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the newly bare forest floor and creating the perfect environment for wildflowers.

Human development, however, has disrupted this cycle. Wildfires are quickly put out, and many areas are too close to homes and businesses for prescribed burns to be safely conducted.

“It’s getting rare to find early successional habitats,” said Ivone de Bem Oliveira, a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum and co-author of the paper. “So, under the electric transmission lines, we can mimic that environment.”

Utility crews use mechanical and chemical interventions to maintain a safe corridor for energy transmission. Such maintenance activities can act as proxies for the wildfires that historically created successional habitats in Florida. This combination of management tools allows for easier, safer access to electric lines for repairs, improves transmission reliability, reduces long-term vegetation management costs and ensures safety for the habitat and energy consumer.

Florida Museum photo by Chase Kimmel

Methods include mowing, using selective herbicide applications to kill woody vegetation and using equipment to prune trees that get too tall or thick. This is particularly important in Florida, where weather events such as severe thunderstorms and hurricanes may briefly knock out power.

Although Duke Energy prefers to keep its rights-of-way free from coarse, woody debris, sites sometimes fall behind schedule. Curious about how this affected plant and insect diversity, the research team sorted their survey areas by classifying sites based upon measurements of bare ground and coarse, woody debris.

“In the higher intensity management locations, you could easily walk under the powerline, while at mid-intensity sites, one might find shrubs and various raspberry bushes, so you can’t walk in a straight line. In low–intensity sites, it’s hard to even get through the area,” Kimmel explained.

The researchers define the intensity of management not by how often the site is managed, but by what kind of habitat develops as a result. Some rights-of-way were considered high intensity while being managed only every year or two.

Across these sites, the researchers set a total of 2,376 pan traps to collect pollinating insects. These bowls, commonly used in insect diversity studies, are filled with soapy water and often come in bright blue, yellow and white colors. To insects, these colorful pan traps resemble flowers.

Florida Museum photo by Jeff Gage

The researchers collected 11,361 flower-visiting insects in all, representing 33 families. Nearly half were bees, and a quarter were beetles. Flies, wasps, butterflies and moths made up most of the remainder.

Rights-of-way with high–intensity management had the highest abundance and diversity of these insects. These sites also had the greatest number and variety of flowering plants.

Photo courtesy of Duke Energy

“In some of these environments, you often see a rich herbaceous understory because of regular disturbance,” said Jaret Daniels, senior author on the paper and curator at the museum’s McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity. “This also helps support rare plant communities.”

“The public might have a perception that a hands-off approach and letting nature do its thing is best,” Kimmel said. “But that’s not always the case.”

To support a rich and abundant pollinator community, the authors recommend high-intensity management in rights-of-way. This does not mean, as the name may suggest, constant mowing or indiscriminate herbicide applications, but a combination of strategies that target specific plants with the goal of maintaining a successional habitat.

Throughout much of North America, utility rights-of-way connect and bisect every type of landscape, from urban to rural. There are 180 million power lines in the U.S. alone and 5.5 million line-miles of land set aside for them. Using these areas as pollinator habitat could be a conservation game changer.

The long corridors can also help migrating species move more easily. They can help foraging insects travel large distances as they look for food, potentially bringing important pollination activity to neighboring conservation and agricultural lands.

The authors published their study in the journal PLOS ONE.

Joshua Campbell, Emily Khazan, Jonathan Bremer, Kristin Rossetti, Matthew Standridge, Tyler Shaw, Samm Epstein and Alexandra Tsalickis of the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity are also authors on the paper.

Funding for the study was provided in part by the Duke Energy Foundation.

Sources: Chase Kimmel, cbkimmel@ufl.edu;

Ivone de Bem Oliveira, idbem.oliveira@ufl.edu;

Jaret Daniels, jdaniels@flmnh.ufl.edu

Writer: Jiayu Liang, jiayu.liang@floridamuseum.ufl.edu, 352-294-0452