National Marine Fisheries Services

An archaeological site in the Caribbean provides prehistoric evidence of overhunting green sea turtles.

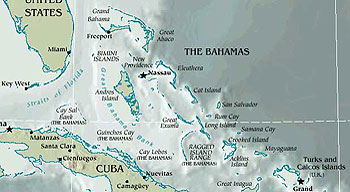

The Cayman Islands, just south of Cuba, are among the only islands in the Caribbean where scientists have found no evidence that prehistoric peoples ever reached their shores. When European explorers reached the Caymans in the 15th Century, they recorded their amazement at encountering an enormous abundance of green sea turtles. During the second voyage of Columbus, in 1493, near the Gulf of Batabanó in southwest Cuba, Andres Bernáldez described seeing so many sea turtles “that it seemed as if the ships would run aground on them, and their shells actually clattered” along the topsides. It is likely that similar turtle populations characterized the waters surrounding Turks and Caicos Islands, located roughly east-northeast of Cuba’s southeastern tip, when native peoples first arrived about 1300 years ago.

A study in 1997 estimated the pre-Columbian turtle population of the Caribbean to have been between 33 and 39 million adults. But this figure describes population numbers before Europeans began harvesting green turtles, and it does not take into account the effects of exploitation by prehistoric peoples. This is a significant omission because sea turtle meat was esteemed in the Amerindian diet of the Caribbean. Since sea turtles were not available in high quantities everywhere, hunters came to the turtle grounds. One of these turtle harvesting sites, Coralie, was found and investigated in Grand Turk, within the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Image courtesy of Caribbean Magazine

The Coralie site was settled in the 8th Century and interestingly, the pottery that settlers brought with them displayed only one decorative motif-turtles. As archaeologists reconstruct what life was like in Coralie, great deal of the activity appears to have revolved around turtle preparation and consumption. The inhabitants likely used this island’s natural salt deposits to cure and store surplus turtle meat, some or all of which would have been taken back to the Greater Antilles. Turtle bones excavated from this site represent a staggering estimation of 5,000 pounds of processed turtle meat. Scientists studying the turtle bones have learned details about the age of the turtles most commonly harvested, how they were captured and how they were processed.

Humerus bones recovered from Coralie indicate that the harvested population was 25 percent juveniles, 60 percent sub-adults and 15 percent adults. Sub-adults weighed between 50 and 150 pounds and were up to 2 feet 6 inches long. Sub-adults graze on turtle grass and occasional invertebrates in shallow tidal flats until reaching adulthood at about 30 years of age, at which time they migrate to feeding grounds in deeper water. It takes even longer for females to reach sexual maturity, which occurs between the ages of 40 and 60.

The archaeological record of Coralie reveals that turtle hunters of Grand Turk primarily harvested sub-adults from their shallow coastal feeding grounds, but the site also included remains of two hatchlings, each about 2 inches long. This shows that Grand Turk once supported a nesting population of green turtles and that the few adult turtles in the site were captured while out of the water laying their eggs on an eastern Grand Turk beach. Females are almost entirely defenseless when laying eggs, and capturing them can be as simple as turning them over. There are no historic records of green turtles nesting on Grand Turk, although there are past reports of turtle nesting beaches in the Caicos Islands.

Image courtesy of TurtleTrax

Because of their predictable habits and clustered populations, turtles are easy to hunt. Turtles sleep on shallow coral flats and migrate between feeding and sleeping sites along the same daily route. Though turtles can hold their breath for 10 to 20 minutes, they must regularly surface to get air. They exhale multiple times upon surfacing and can be heard and located before they dive again.

Worldwide, harpooning is the most common method of capturing turtles, accomplished with a hardwood harpoon tipped by a short detachable point secured to a line. Turtlers work in teams of two; one maneuvers the boat while the other harpoons. In the turtle remains from Coralie, there are a few examples of carapaces punctured with round holes that may have been made from harpoons. The frequency of sea turtle remains decrease over time in the Coralie site, which indicates that the green turtle population declined over time and that there were less for the Taino to hunt. The largest specimens came from the earliest deposits, which indicate that younger and younger turtles were hunted as they became more and more scarce due to overhunting.

Image courtesy of Cayman Islands Turtle Farm

Nets may have also been used to capture turtles. Historic records show that as late as 1878, green turtles were being harvested in nets from the mouth of North Creek, a large inland lagoon on Grand Turk, and exported to the commercial New York market. The Coralie site is located on the shore of North Creek and it is likely that turtles were captured prehistorically inside this lagoon.

Also at the Coralie site, turtle bones were recovered within large cooking hearths. Apparently, little butchering of the turtle was done before roasting. The hearths contained long bones, the shell bones, some broken skull pieces and even the small bones of the fins and tail. Eggs from females, green fat deposits, and blood would have been removed and consumed before roasting. The turtles were roasted whole, in their shells.

Green turtles can live for more than 100 years, but despite their capacity for longevity, they are highly susceptible to population declines due to several factors. First, the fact that they take so long to reach sexual maturity coupled with the long period of their life when they inhabit shallow waters leads the immature turtles to become easy targets for coastal-dwelling people such as the prehistoric people who settled Grand Turk. Hunting pressures on the sexually immature sea turtles may have led to declining reproductive rates and, ultimately, population declines.

Few of the staple foods in the prehistoric Taino diet still inhabit this region today. The process of resource overexploitation is not a new one. Rather, it began prehistorically — as the green turtles from Coralie illustrate. This may run counter to the popular idea that indigenous people managed their natural resources in harmony and balance with the natural environment, but overexploitation of resources by prehistoric people is actually a theme repeated many, many times throughout the archaeological record.

Bill Keegan is Curator of Caribbean Archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History. Betsy Carlson is a zooarchaeologist who specializes in Caribbean prehistory. She is a senior archaeologist with Southestern Archaeological Research Inc. in Gainesville, Fla.

Original version published in “Times of the Islands” Spring 2008 issue; adapted and edited version reprinted with permission.

Learn more about the Caribbean Archaeology collection at the Florida Museum.