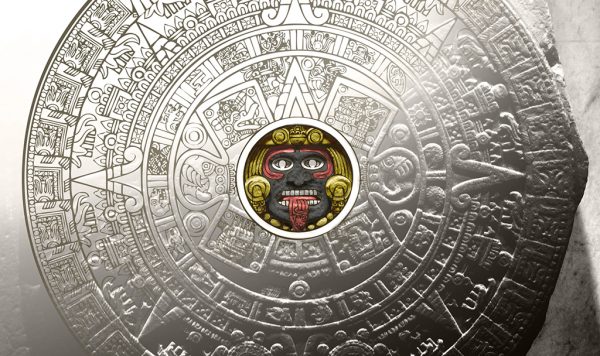

A new study on one of the most important remaining artifacts from the Aztec Empire, a 24-ton basalt calendar stone, interprets the stone’s central image as the death of the sun god Tonatiuh during an eclipse, an event Aztecs believed would lead to a global apocalypse accompanied by earthquakes.

Many scientists believe the heart of the stone to be the face of Tonatiuh (pronounced toe-NAH-tee-uh), atop which Aztecs offered human sacrifices to stave off the end of the world. Researcher Susan Milbrath, a Latin American art and archaeology curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History, offers the new, ominous interpretation of this symbol in the February print edition of the journal Mexicon.

“They did perhaps have a more foreboding look on their future than people in today’s societies do,” she said. “But the Aztecs were more sophisticated in terms of astronomy than people realize.”

Stone’s grisly past

Florida Museum graphic by James Young, with images from El Commandant and Keepscases / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0

The Aztec Empire dominated much of present-day central Mexico from about 1325 until the 1520s, when the Spanish colonized the region, assimilating locals to live more like their European conquerors. The Spanish buried the 12-foot-wide calendar stone, also known as the Sun Stone, face down before it was uncovered in 1790.

The stone, which was displayed in the main square of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, in present-day Mexico City, was probably where the most treasured captives were sacrificed, Milbrath said.

“That almost made it like a stage for public ritual,” she said.

The original stone is housed at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, but the Florida Museum of Natural History displays a full-size replica in the Dickinson Hall courtyard on the University of Florida campus.

Studying the sun to predict the future

Milbrath said early cultures such as the Aztecs and Mayas tracked the sun’s movements to predict future events, such as weather patterns and astronomical cycles.

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

“It’s quite natural for people to want to predict cycles,” she said. “Once people started tracking both the sun and the moon and noticing the eclipses that occurred, it probably became central to their religion.”

Like other early Mexican societies, the Aztecs relied heavily on agriculture, growing maize, beans and squash to sustain their population. But their dependence on the sun for agriculture was also accompanied by a belief that they had to feed the sun with the blood of human sacrifice to keep it alive.

The Aztecs sacrificed a prisoner on the calendar stone on the date 4 Olin, the day they believed the world would end. The day repeats every 260 days in their calendar cycle. With succession of the cycle, another prisoner was sacrificed and the sun rose again the following day. Tonatiuh lived on.

The priests, high in the Aztec society chain of command, were responsible for charting astronomical phenomena, including the eclipse that would bring impending doom, Milbrath said.

They may have known that no eclipse would come on 4 Olin during the height of the empire. Based on the Aztec calendar system, a solar eclipse would not fall on that date until the 21st century, she said.

“When they created their mythology, they made sure that 4 Olin would never occur with an eclipse in their world,” she said. “The possibility of purposeful manipulation should not be ignored.”

Claws, human hearts and a darkened sun

One of the most important features of the stone, Milbrath said, may have been washed away over time: paint. In commonly used images, including one displayed beside the original stone, the surface is colorful, with a headdress- and necklace-adorned Tonatiuh depicted as a blue and red figure framed in yellow.

Florida Museum of Natural History photo by Susan Milbrath

These colors are often used in Aztec paintings of Tonatiuh as a living god, Milbrath said. But some evidence suggests the image of Tonatiuh may have been left unpainted or colored black, like the sun during a solar eclipse. Black was also used in another important eclipse image of the dying sun in another Central Mexican codex. Tonatiuh’s tongue, shown on the Calendar Stone as a knife sticking out of his mouth, was a common icon of death as well, she said.

Surrounding Tonatiuh are claws clutching human hearts, alluding to an eclipse monster — the embodiment of eclipses in other Aztec paintings and drawings — and a circle of signs symbolizing the 260-day calendar used to predict agricultural cycles and future events.

On the outermost ring, fire serpents — open-jawed snakes with flames on their bodies and starry snouts — represent a constellation closely associated with the sun in the dry season, when the sun’s powerful rays were most brilliant, Milbrath said.

For Aztecs, astronomy blended with religion

The Aztec obsession with astronomy was not an anomaly, she said.

“Astronomy and religion have always been connected,” she said. “It’s just innate, because without electric lights, all you have to do at night is look up and see the vastness of the stars in the sky.”

Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

Aztec people likely tried to defy and combat the forces they thought would destroy the sun during an eclipse, when darkness covered the sun and harm could come to people, Milbrath said.

“Pregnant women stayed indoors because they thought their children would be born with horrible deformities,” she said. “Most of the details of how the Aztecs dealt with solar eclipses are not well-known, but they definitely did try to scare away the monster they thought was eating the sun.”

Milbrath said although human sacrifice was an important practice in Aztec culture, scientists should not overlook what they accomplished by being able to predict eclipses.

“I hope people have an appreciation of the Aztecs not as some bloodthirsty population,” she said. “They probably killed a lot less people than we have in the 20th century through collective warfare.”

“I’m afraid that warfare is endemic to our cultures. We’re sacrificing people all the time, in different ways,” she continued. “I’m not sure that we’re more sophisticated than they were.”

En españolLearn more about the Latin American Archaeology Collection at the Florida Museum.