Florida Museum photo

Call it a galactic joy ride, but on Oct. 23, 2007, NASA’s 120th shuttle mission launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, with hundreds of thousands of miniscule stowaways stashed inside the solid rocket boosters, unbeknownst to anyone.

Had they hitched their ride on the main shuttle, the gobs of mysterious yellow particles may have breached the borders of space, but as it turned out the 20- to 25-micron-sized yellow grains made it an unprecedented 28 miles above Earth’s surface – to the outer edge of the stratosphere where the solid rocket boosters detached from the main shuttle.

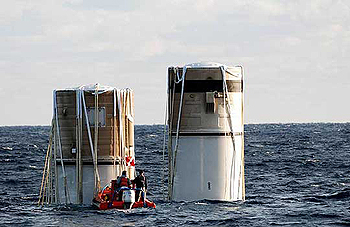

The space-bound stowaways then endured the searing heat of re-entry and plunged, safely inside the boosters, into the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Jacksonville. They landed seven minutes later and about 160 miles downrange from their departure at the Kennedy Space Center’s launch pad. Soggy with seawater, the stowaways morphed into a gooey, gunky sludge.

NASA contractors charged with retrieving the solid rocket boosters for cleaning and refurbishing back at the space center were dismayed to find the gunk clogging a drain line on the booster’s frustum. The frustum is the conical-shaped “brain” at the top of the solid rocket booster that houses extremely sensitive computers and wiring.

Florida Museum photo

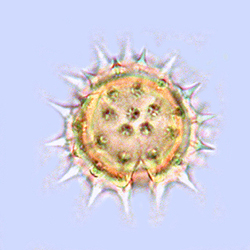

Wary of the foreign substance, the contractors took samples and used scanning electron microscopy for a closer look. The image revealed a microcosm of delicately shaped geometric pods pocked and riddled with complex architecture: smooth folded arcs, deep pitted pores and tall pointy spikes.

They looked an awful lot like pollen grains.

So the NASA contractors called on Florida Museum of Natural History palynologist David Jarzen for help. They peppered him with questions: Was this substance pollen? Where did it come from? How did it get in the frustums?

Jarzen is a courtesy research scientist in the Florida Museum’s paleobotany and palynology laboratory and he thinks of palynology, the study of pollen, as strikingly akin to forensics.

“Palynology is a tool, and we use the study of pollen to answer many questions about things,” he said. “Whether those questions are about things that took place 65 million years ago in the Cretaceous, or something that happened last week doesn’t really matter, because the pollen tells us the answer in both cases. That’s the beauty of pollen – it preserves, it lasts forever.”

Jarzen usually studies fossilized pollen, but the NASA project presented a new challenge.

“When I looked at their samples, there was not a doubt in my mind it was pollen,” he said. “It didn’t take long to identify the grains either, because 99 percent of the composition was from just two species: Brazilian pepper and a plant from the Asteraceae family — the sunflowers.”

Florida Museum photo

The Asteraceae are very common in Florida, and Brazilian pepper is an invasive species infesting large swaths of southern Florida. Because the Kennedy Space Center is nestled within 140,000 acres on the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, there is plenty of native habitat for the plants to spread their roots. And to the north, Canaveral National Seashore provides an additional 57,000 acres of native coastal habitat.

“Identifying the pollen wasn’t that difficult,” Jarzen conceded. “I know these as my good friends,” he said, gesturing to a poster in his office depicting enlarged pollen grains endemic to the southeastern U.S.

“But I had to learn a few details about how NASA does things before it made sense why there was so much pollen clogging the frustum drain line,” Jarzen said.

He spoke with a contact at United Space Alliance, the contracting agency responsible for recovering the solid rocket boosters after each launch, and learned the boosters were often left outside in a staging area for lengthy periods of time prior to a launch.

“It could be days, weeks or even a month or two that they were sitting outside,” Jarzen said. “And then I learned that they had a lot of bees around the launch pad, and it clicked. Bees love to find little holes and make nests in trees and branches – wherever, it doesn’t take much. So they see these frustums sitting out there, and they see these little drain holes that have a perfect diameter opening to put little balls of pollen in there as food storage.”

NASA photo

Jarzen believes bees were stashing their pollen loads in the drain lines for several weeks before the Oct. 23 launch.

“Insects are often host specific, they will collect from specific flowers and selectively accumulate certain pollen species,” Jarzen said. “So it’s most probable these bees collected the pollen from the Brazilian peppers and the Asteraceae present on the property and deposited them in the drain lines.”

Jarzen discounted the possibility that airborne pollen had accumulated in the lines because he said airborne mixtures are composed of a greater variety of species and always have mold and fungal spores present, especially in Florida’s wet climate. He said the absence of these spores, and the dominance of the two pollen species provided a recognizable insect signature.

Pollen grains are sturdy packages that contain the male genetic materials necessary for plant reproduction. They are designed to travel long distances by air, or by clinging to an insect, and to land undamaged on a receiving flower. Once there, they are stimulated to grow pollen tubes that competitively shoot down a flower’s internal structures in a race to be the first to deposit their genes and create new life.

Some pollen species are so indestructible they are preserved in soils and sediments for thousands to millions of years. But their tough suits of armor weren’t designed to shoot 28 miles into the sky — four-and-a-half times higher than an average commercial airliner travels — or to experience the 12.5 million Newtons of thrust the boosters provide at lift-off.

United Space Alliance photo

When the booster rockets return to Earth, they are shielded to protect against the extreme heat, which can rise to more than 700 degrees Fahrenheit during re-entry. When pollen is heated to more than 212 degrees Fahrenheit, it undergoes a systematic darkening, termed “thermal maturation.” Yet Jarzen’s pollen samples from the interior of the frustum were a zingy, fresh yellow.

“It’s a real testament to NASA’s thermal protection design of the frustums that these pollen appear unscathed despite traveling through the heat of re-entry,” Jarzen said.

An object 28 miles above the Earth’s surface is at the upper edge of the stratosphere. When people observe a meteor blazing its way to Earth, the heat they see is typically generated as the meteor passes into the upper stratosphere.

“This was a great opportunity for the museum to collaborate with NASA, I felt so honored when they asked me to work on this,” Jarzen said. “I’ve been working with pollen for decades, and it never ceases to amaze me what we can learn from it.”

Perhaps NASA learned something too. Pre-launch drain line plugs, anyone?