Three grants from the National Science Foundation will enable the Florida Museum of Natural History’s invertebrate zoology division to contribute crucial specimen data and images to online research networks. The grants represent the first two major funding initiatives to digitize modern marine organisms, as well as the first to focus on mollusks. The online databases will include specimens from nearly every major invertebrate zoology collection in the U.S.

Scientists digitize specimens by uploading images and information such as when and where they were collected to online databases. Digitization makes museum collections “visible,” said Gustav Paulay, curator of invertebrate zoology at the Florida Museum. It provides vast sets of searchable records of marine invertebrates – such as sea stars, corals and crabs – that may otherwise be restricted to museum shelves.

The Florida Museum’s invertebrate zoology division is a world leader in marine digitization efforts, with nearly 700,000 records online already. But new software will also enable researchers to group collection data thematically, resulting in user-friendly portals made for a wide range of public uses, including education.

“Photos can be used in so many different ways. Look at now, with COVID-19, what teachers need to do to have a digital classroom,” said John Slapcinsky, invertebrate zoology collections manager at the Florida Museum. “Those types of data and images are going to be really beneficial for those sorts of learning experiences. And I don’t think there’s anybody else that can provide that level of information.”

A nationwide effort to digitize marine invertebrates

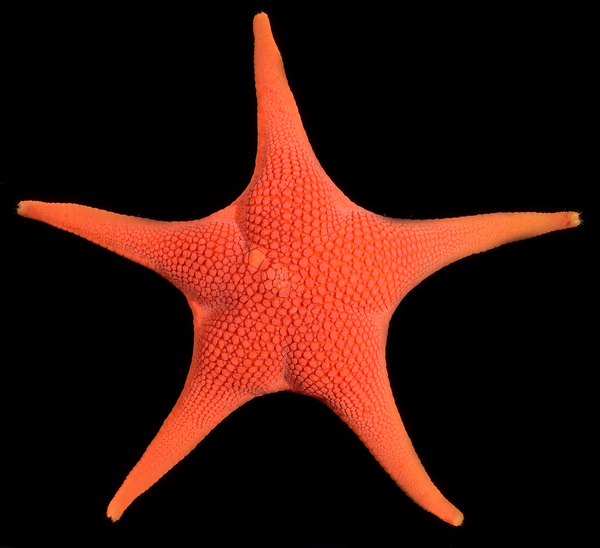

Paulay is a principal investigator on a $4.4 million grant shared among 19 institutions to digitize about 7.5 million marine invertebrate specimens such as jellyfish, sponges and worms. The grant kicks off one of the largest marine digitization efforts in the U.S.

Florida Museum invertebrate zoology photo

The Florida Museum’s collection of marine invertebrate images, tissues and DNA – among the world’s largest – will bolster specimen data across institutions, Paulay said. He will also lead the team’s efforts to align specimen names between web databases and collections, enabling scientists to more accurately track species records over time, even if names have changed with reclassification. Paulay, who often leads intensive expeditions to document all marine biodiversity in a given area, added that collecting efforts remain crucial.

“What we need to do today – even more than digitize collections – is to collect what’s out there before it’s gone,” Paulay said. “The need for this can get buried in all this digitization excitement. So much of biodiversity is not represented in existing collections and there remains an urgent need to collect and document this.”

Digitizing mollusks along the Eastern Seaboard

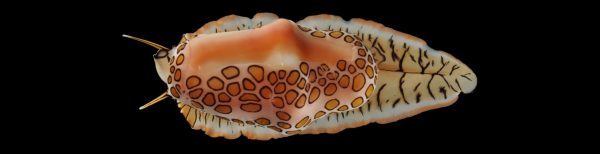

Slapcinsky is a principal investigator on a $2.3 million grant to digitize 4.5 million mollusk specimens found along the East Coast. The funding will result in the first online collections network dedicated to marine mollusks and will help sharpen scientific understanding of how mollusk distributions have changed over time.

Florida Museum invertebrate zoology photo

“Digitization is really important because the trends that happen in the environment happen at a slower scale than we see in our lifetimes,” Slapcinsky said. “Having this information digitally available means you can start to see patterns that wouldn’t be available to a person living in a single time period.”

Digitizing rare land snails

Slapcinsky is also a principal investigator on a $1.3 million grant to digitize 3.6 million Pacific Island land snails and upload them to the Pacific Island Land Snail Biodiversity Repository, or PILSBRy. The grant funded the first major digitization initiative focused on mollusks.

Among the most endangered animals on the planet, Pacific Island land snails are highly imperiled. But hidden diversity remains: Slapcinsky and collaborators at the Bishop Museum recently described two new native Hawaiian land snail species. One is the first living species in its family to be described in 60 years, and the other is the last remaining species in its genus.

Florida Museum photo by John Slapcinsky

Slapcinsky said digitizing historic and recent specimen records helps land managers protect remaining snail populations by enabling them to see their distributions.

“When you look at two maps and see a species used to be all over and now it’s just in one spot, that’s when you know you better get out there and take steps now while there’s still a chance to save it.”

Sources: Gustav Paulay, paulay@flmnh.ufl.edu;

John Slapcinsky, slapcin@flmnh.ufl.edu