Tourists who comb Florida’s sandy beaches for exotic shells are probably unaware that they’re also picking through bits of geologic history. Incalculable numbers of fossilized marine invertebrates—clams, snails, crabs, sand dollars and corals—pepper the Sunshine State’s beaches and terrestrial interior. These small fossils may help natural history researchers complete a picture of Florida’s past.

Photo by Eric Zamora

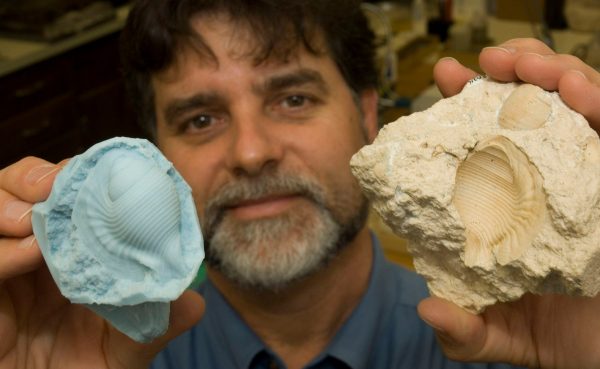

One invertebrate paleontologist is helping fill the gaps by focusing on Florida’s “phantom fossils,” or moldic, three-dimensional impressions of invertebrate marine organisms left in sedimentary rocks. Roger Portell, an invertebrate paleontologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History, says moldic fossils are difficult to study because their actual shells and hard tissues dissolved thousands to millions of years ago, leaving only phantom impressions. (See sidebar below.)

“Some of my colleagues used to tease me about studying fossils that ‘weren’t really there,’ ” Portell said. “But over 20 years, I’ve fine-tuned a method of making rubber casts from the moldic fossils and we’ve actually described a few dozen new species from the casts.”

Photo by Eric Zamora

Many traditional casting methods rely on clay or latex, which dry out quickly and distort a fossil’s features. So Portell began experimenting with casting materials, looking for the perfect combination of pliability, durability and fine detail.

“Our ultimate goal is to produce a three-dimensional copy of what the shell looked like,” Portell said. “We want to make the best possible replica we can, and we want it to last.”

How It’s Done

Portell and his technicians start the process by carefully using a rock saw to trim rock specimens they collect in the field. A low-sulfur clay is then heated to a malleable temperature and rolled into a one-quarter-inch thickness with a rolling pin, like pie crust. Clay strips of various widths are then cut and wrapped around the trimmed fossils to make a dam, a high collar of clay that extends past the fossil’s surface to hold the liquid cast material.

Phantom Fossils: How They’re Made

After death, most invertebrate organisms decay but some undergo specific processes that yield moldic fossils. These fossils are impressions in sedimentary rock of what the organism’s exterior and interior surfaces looked like in life. When an invertebrate marine organism such as a clam dies, it sinks to the sea floor where one of two things happens: it either breaks down through decay, or it is buried in protective sediment such as sand, clay or mud. If the organism is buried, sediment particles may settle and harden around the shells’ exterior, recording a three-dimensional impression of its features. Sediment may also seep into its interior spaces, taking the place of once-living tissue. Over thousands or millions of years, the actual shell may dissolve while the internal and external molds harden into sedimentary rock, leaving a phantom fossil–a finely detailed impression of how the organism looked.

Photo by Eric Zamora

After the fossils are trimmed and wrapped, Portell and his team begin creating a cast of each piece. Portell researched different rubber compounds for the cast material before settling on a vulcanized rubber, a material that has undergone a heat and chemical process to make it stronger. Most rubber products are vulcanized, because rubber in its natural state is easily deformed. He said this rubber is the same kind “used in industrial mold-making for the automotive industry” and that it has a shelf life of about 100 years before it becomes brittle. An activating agent, a catalyst that hardens the casts, is mixed with the rubber compound in a 1:10 ratio based on weight and the mixture is then placed in a vacuum chamber to remove the air.

Next, the cast material is carefully poured down the side of the prepared fossil void, as if pouring a glass of beer, pushing the air from the void ahead of the rubber. Then the poured molds go back into the vacuum chamber for a second round of “de-gassing.” After all the air is removed, the molds are left to cure for 12 to 24 hours and then “peeled,” which requires removing the clay dam and carefully coaxing the pliable rubber cast from the void in the rock. For deep voids the cast is reinforced with a wooden or metal dowel.

“What you want to avoid is having the cast break off in the void,” Portell said. “Because then you have to pick it out with a dental instrument, and you end up scraping the inside of the mold which will ruin the sculptural features you’re trying to preserve with the cast.”

What emerges can be stunning: an intricate, beaded pattern on ancient marine mud snails, the delicate aperture of the land snail Praticolella or the beautiful sculpture of a winged conch Platyoptera.

Because a casts’ features can be so detailed, Portell has successfully produced electron scanning micrograph images of the peeled casts. “These peels were so good that you can’t tell the image isn’t of a real shell,” he said.

Portell has made casts of hundreds of shells, crabs, echinoids, tube worms and even the tracks of a hermit crab in soft mud. He sees the work as laying a foundation for the next generation of researchers to finish describing the species and fleshing out the details of Florida’s fossil record.

“I doubt I’ll have enough time before I retire to describe all the new genera and species that I’ve found in these moldic fossils, though it would be nice to feel like I’ve made a dent,” he said.

Learn more about Invertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum.