Plants contain a vast array of chemical compounds, some of which can be poisonous to humans, pets and livestock. These toxic compounds benefit plants by deterring plant-munching insects, protecting against microbial infections and creating a barrier between injured and healthy tissues. Some plant species also produce toxins known as allelochemicals that give them a competitive advantage over nearby plants by inhibiting their neighbors’ germination, growth and reproduction.

There is a widely held misconception that plants are either poisonous or safe. However, the extent to which our bodies react to the chemical compounds in plants really depends on the dosage – that is, the amount to which we are exposed. This idea is attributed to the 16th century Swiss physician Theophrastus Paracelsus who argued that it is not the substance that is toxic, but the amount. Paracelsus suggested that the right dose is what differentiates a poison from a remedy.

Depending on the dose, the effects of a particular plant compound on the body may range from benign to therapeutic to harmful or even fatal. This is known as the dose-response relationship, a central concept in toxicology, the scientific study of poisons. Many of the plants that we think of as poisonous or unsafe, such as the garden foxglove, are actually medicinal when administered at an appropriate and controlled dose.

In addition to dose, several other factors influence how we respond to a potentially toxic plant compound:

- Frequency and duration. Sometimes a single dose might fail to induce any negative response, but repeated doses over a more extended period of time may lead to more noticeable effects.

- Route of exposure. The effects of a plant compound on our bodies often depends on whether it is ingested, injected into the bloodstream, inhaled or rubbed on the skin.

- Which part of the plant, maturity of the plant, time of year and environmental conditions. Not all plant parts contain the same concentrations of chemical compounds. Sometimes toxins accumulate in a specific plant organ or at a particular developmental stage, such as immature fruit. Toxins can also become concentrated in plant tissues in response to temperature extremes or under drought conditions.

- Species differences in sensitivity. Some plant compounds might be dangerous for pets or livestock or birds, but not for people, or vice versa. Avocados, for example, are safe for humans to consume, but toxic to birds, rodents, rabbits, goats, cattle and horses.

- Individual differences in sensitivity due to body mass, age, health status or allergies. Young children, seniors, individuals with small bodies and those with compromised immune systems are all more sensitive to relatively small amounts of potentially toxic compounds. Young children and puppies are particularly vulnerable to poisoning since they have small bodies and immature immune systems and tend to explore their surroundings with their mouths.

Poisoning may be acute or chronic. In acute poisoning, a single exposure results in rapid absorption of the toxin, leading to symptoms that can be sudden and severe, but often reversible. Chronic poisoning results from repeated exposure over days, months or years. In cases of chronic poisoning, symptoms typically are not immediately apparent, but develop over time, may ultimately be severe and are more likely to create irreversible bodily damage.

The best way to play it safe is to never eat a plant unless you are 100% certain what it is. Don’t assume that because you’ve seen a bird or a deer consume a particular plant that it is safe for you to eat! Since plants can absorb toxins – such as pesticides, heavy metals and petrochemicals – from the environment, we also need to be alert to whether any harmful compounds are present in the soil or water around the plant. Foraging for wild edible plants requires knowledge and skill and is best learned in the company of an experienced forager. When foraging for wild edibles, be aware of toxic lookalikes.

Quite a few plants in our gardens and natural areas have the potential to make us sick. Many of them might cause mild digestive upset or other temporary discomfort. But a handful of common, widespread plants in Florida can cause severe symptoms at a relatively low dose. These are key species to know. If you have pets or small children, consider removing these plants from your garden or at least limiting access to them.

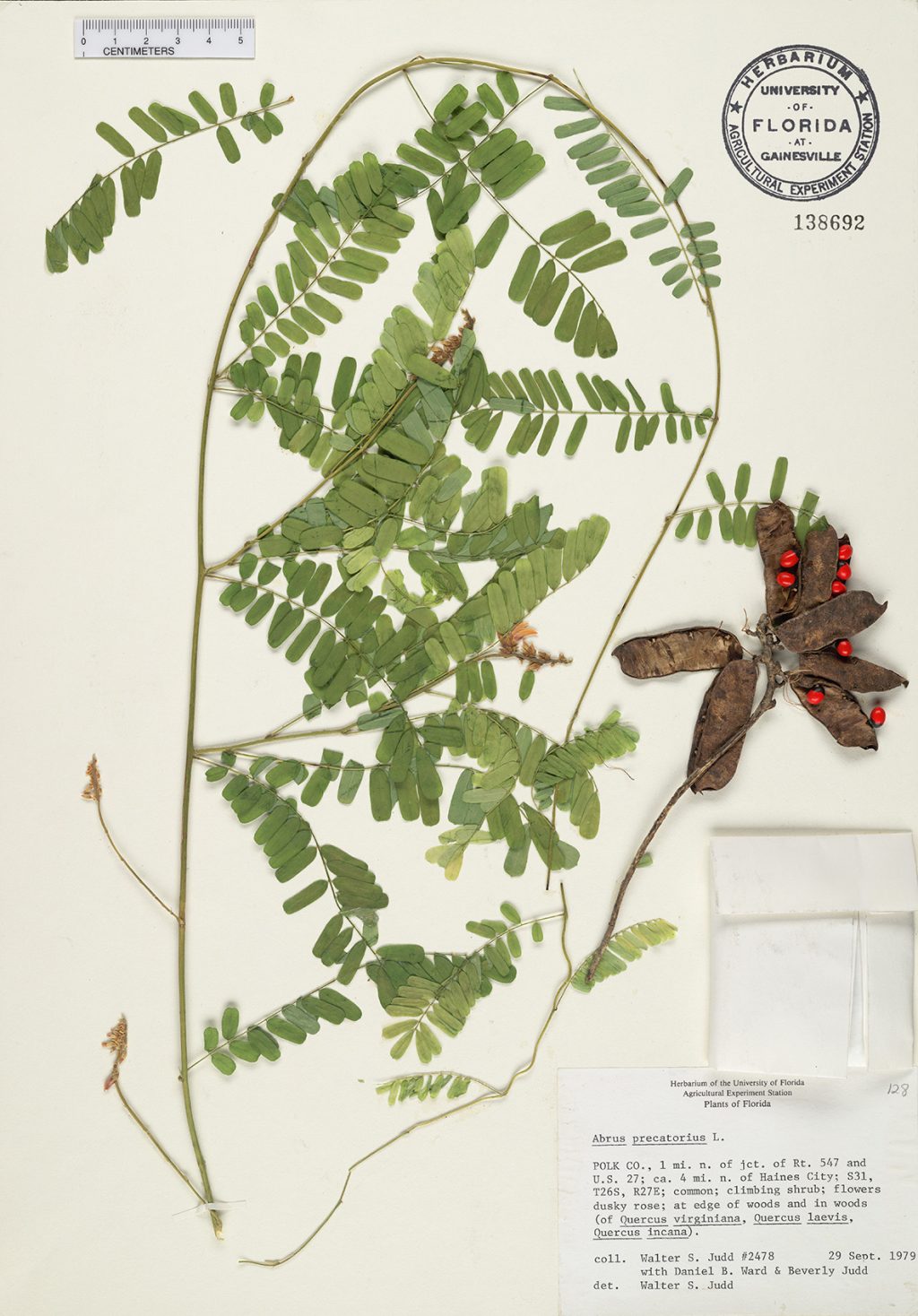

1: Rosary pea

Rosary pea (Abrus precatorius), also known as jequirity pea or crab’s eye pea, is a vine in the legume family. Originally from the Old World, rosary pea has become established on the Florida Peninsula from Marion County southward. It often grows as a weed on disturbed sites such as residential landscapes, roadsides and croplands. Not only is rosary pea listed as a Florida noxious weed (regulated invasive plant), but it is also highly poisonous. The toxin, a protein called abrin, is concentrated in the seeds, which are shiny and scarlet with a black eye. Because they have a hard, durable coat, the seeds can pass through the digestive system without any ill effects. However, they are potentially fatal at low doses when chewed (or if the seed coat is otherwise damaged), burned and inhaled, or injected under the skin. In Africa and India, a paste made from the crushed seed has been used as an arrow or spear poison. Because the seeds are colorful and sturdy, they are valued for beadwork and other crafts.

2: Castor bean

Castor bean (Ricinus communis), which is in the spurge and poinsettia family, is a large, robust non-woody plant from northern Africa. It is widely cultivated as an ornamental for its bold, tropical-looking foliage and interesting, spiny seed capsules. Castor bean is also grown commercially as a source of seed oil used in cosmetics, paints, plastics and lubricants. In Florida, castor bean has escaped from cultivation and become established throughout the state, particularly in frost-free areas. The toxic compound in castor bean, ricin, is structurally similar to abrin in rosary pea. It is also most concentrated in the seeds, which are tan with darker brown marbling. Ricin is poorly absorbed by the digestive systems of ruminant livestock, such as cattle or goats, but poses a greater risk to humans and pets. Castor oil, which was once popular as a cure-all and laxative, is heat treated and refined to remove any toxic ricin.

3: Oleander

Oleander (Nerium oleander), also known as rose bay, is native to the Mediterranean region eastward to India and southern China. It is in the same family as frangipani and milkweed. Oleander is grown as a heat- and drought-tolerant evergreen flowering shrub in gardens throughout Florida. It has also escaped from cultivation and become established in the wild at scattered locations around the state. There are hundreds of cultivated varieties of oleander, which vary considerably in size and have single or double flowers in shades of pink, red or white (less often, yellow or orange). All parts of the oleander plant, including the milky latex produced by cut stems or leaves, contain a variety of cardiotoxic compounds that impact heart function. Many animal species are affected by the toxins, including humans, pets, livestock and some wildlife. In people, poisoning has been attributed to eating honey made from oleander flowers, inhaling smoke from burning branches, holding flowers or stems in the mouth, using cut branches to stir soup or roast meat over a fire and incorporating leaves or flowers in herbal teas.

4: Gloriosa lily

Gloriosa lily (Gloriosa superba), also known as flame lily or climbing lily, hails from Africa and Asia. It is a common flowering vine in Florida gardens and sometime escapes and establishes in the wild. Gloriosa lily climbs via tendrils at its leaf tips and has large, showy flowers that are usually bicolored yellow with red, orange or purple. All parts of the plant contain several toxic compounds, including the alkaloid colchicine. The toxins are highly concentrated in the rhizomes (tuberlike, underground stems). Most documented cases of poisoning from gloriosa lily are in humans rather than pets or livestock, and symptoms of colchicine poisoning typically occur two to six hours after ingestion. Be aware that many other types of garden lilies grown in Florida also contain various toxic alkaloids and can cause poisoning if consumed. These include amaryllis, daylilies, rain lilies, Easter lilies, blood lilies, hurricane lilies, crinum lilies and clivia lilies, also known as Natal lilies.

5: King sago

King sago (Cycas revoluta), also known as sago palm, is not a true palm, but a member of the cycad family native to Japan and southern China. This large evergreen plant with stiff, palmlike leaves is ubiquitous in Florida landscapes, is sometimes cultivated as a houseplant and occasionally escapes into the wild. All parts, but especially the seeds, contain a pair of toxic compounds, called BMAA and cycasin. Poisoning has been documented in humans, livestock and pets. Chronic exposure can cause cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. The seeds, which are about the size of a small walnut with a bright reddish-orange covering, are a common cause of poisoning in dogs, resulting in potentially fatal liver failure. Related species include the cardboard palm (Zamia furfuracea) and our native coontie (Zamia integrifolia). Both are also common in Florida gardens and pose a poisoning risk to dogs.

6: Spotted water hemlock

Spotted water hemlock (Cicuta maculata), also known as spotted cowbane, is a large, shrubby member of the carrot and parsley family. Occurring throughout North America, it is one of our most toxic native plants. In Florida, spotted water hemlock is frequently found in swamps, marshes, ditches, riverbanks and other wet sites. It is not likely to pop up in the typical suburban garden, but you may encounter it if your landscape includes or borders on a low, damp natural area. Several different toxic compounds, including the nerve poison cicutoxin, occur in all parts of the spotted water hemlock plant, but are most concentrated in the roots. There have been numerous cases of adults and children fatally poisoned after eating this plant, mistakenly thinking it was wild carrot or parsnip. The foliage is reportedly distasteful to most species, but not cattle. In both humans and livestock, consuming spotted water hemlock can cause violent convulsions and death by cardiac or respiratory failure in a matter of a few hours.

In the event of a possible plant poisoning, call your physician, veterinarian or Florida Poison Control (1-800-222-1222). Be prepared to tell them which plant and which part of the plant was eaten, how much was consumed and whether there are any immediate symptoms. It’s always a good idea to take a physical sample or photos of the plant to the emergency room along with the patient, especially if you are uncertain what type of plant it is.

Marc S. Frank is an Extension botanist and a biological scientist in the University of Florida Herbarium.